Source: statnews.com

The arrival in 2012 of a daily pill to prevent HIV infection was widely hailed as a breakthrough that could drive new infections worldwide to very low levels. Eight years later, it is having a strong impact in some places and little or none in others.

The real-world impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis, PrEP for short, certainly isn’t living up to its high expectations among young women in sub-Saharan Africa, who account for more than one-quarter of the 800,000 new HIV infections that occurred last year in the region.

The complexities around taking a daily PrEP pill is one reason this therapy is having a limited impact there. A more fundamental problem is a delay in fully engaging African women, including African women scientists, in developing and testing new tools for fighting HIV.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a new version of PrEP in October 2019 that, incredibly, was not tested in cisgender women at all, African or otherwise. As a result, it is available only for men and transgender women. It’s a sobering reality that, as we enter the second decade of the 21st century in a world that is supposedly “woke” to the different manifestations of gender inequality, a new tool for preventing HIV infection has arrived with a “men only” label. In Africa, it’s an especially ominous sign.

I am deeply concerned about the 6,000 adolescent girls and young women who become infected with HIV each week around the world. In some countries, girls and young women now account for 80% of new adolescent infections. Overall, young women are twice as likely to acquire HIV as young men.

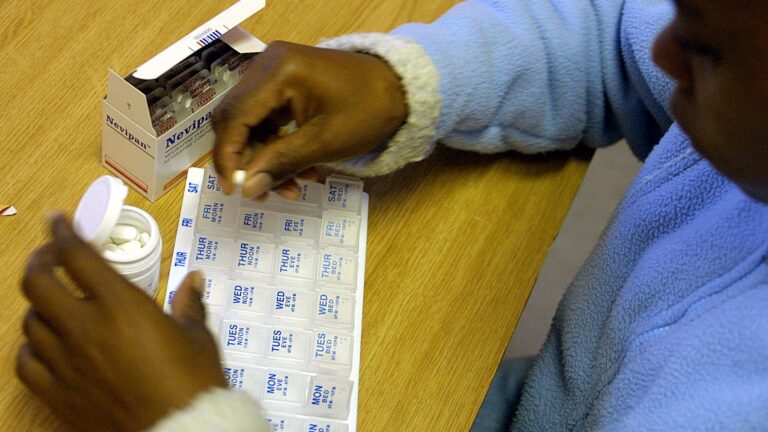

To be fair, there have been efforts to conduct clinical trials with PrEP in African women. And the majority of participants in ongoing advanced-phase trials for HIV vaccines, antibodies, and injectable PrEP are women. But the poor results of PrEP trials in women to date should not have baffled some researchers. For example, a PrEP trial involving 5,000 women in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe found no reduction in infections. But that was mainly because many of the participants did not regularly take their pills.

A recent study probing this lack of adherence pointed to social factors, including how taking a daily antiretroviral pill could stigmatize women as being at risk of HIV or even being HIV infected. Some women reported extreme reactions from family members and breakups with spouses or partners.

The broader issue is a failure to understand the circumstances and preferences of African women and adolescent girls who urgently need protection against HIV. Beyond involving women as participants in clinical trials, fighting a disease that, in Africa, disproportionately affects women also requires involving more African women scientists — and African research institutions in general — in leading product development and testing.

In my work to enable development and testing of new HIV vaccines and other preventive agents, I am constantly looking for ways to engage the communities we will be serving, especially young women, to understand what innovations they are most likely to embrace. One area of interest involves the possibility of using manufactured HIV antibodies to develop an injectable product that would provide protection for several months, which would help overcome the adherence challenges associated with PrEP.

Working to ensure that HIV prevention tools are accessible and appropriate for African women and girls offers an approach that could be relevant beyond Africa. This work could, for example, offer valuable lessons for the United States, where PrEP drugs are not being widely used in certain at-risk populations.

We have arrived at a simultaneously hopeful and dangerous moment in the battle against the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Hopeful because new tools are now available and in the research pipeline. Dangerous because, after years of steady declines in new infections, we have hit a plateau, especially among young African women and girls.

Overcoming these challenges demands a significant shift that delivers new investments in African-led and women-led HIV research endeavors across the continent. Research in South Africa has been well represented by women scientists, but that trend is not representative of the rest of southern Africa, East Africa, and West Africa. Recently, there has been a measure of new funding for women scientists that is helping them secure leadership roles in African research institutions and compete for grant support, but much more is needed.

I bring to this work two decades of experience in clinical trial design and implementation. I also bring the experience of being a daughter who lost both of her parents to this terrible disease, and I am also the mother of a young African woman. I believe that these influences make me a better scientist.

We can win the fight against HIV in Africa. But this virus is a resilient adversary. If we truly want to win, we must give African women opportunities to lead the battle.