Introduction to Abdomino Perineal Resection Of Rectum

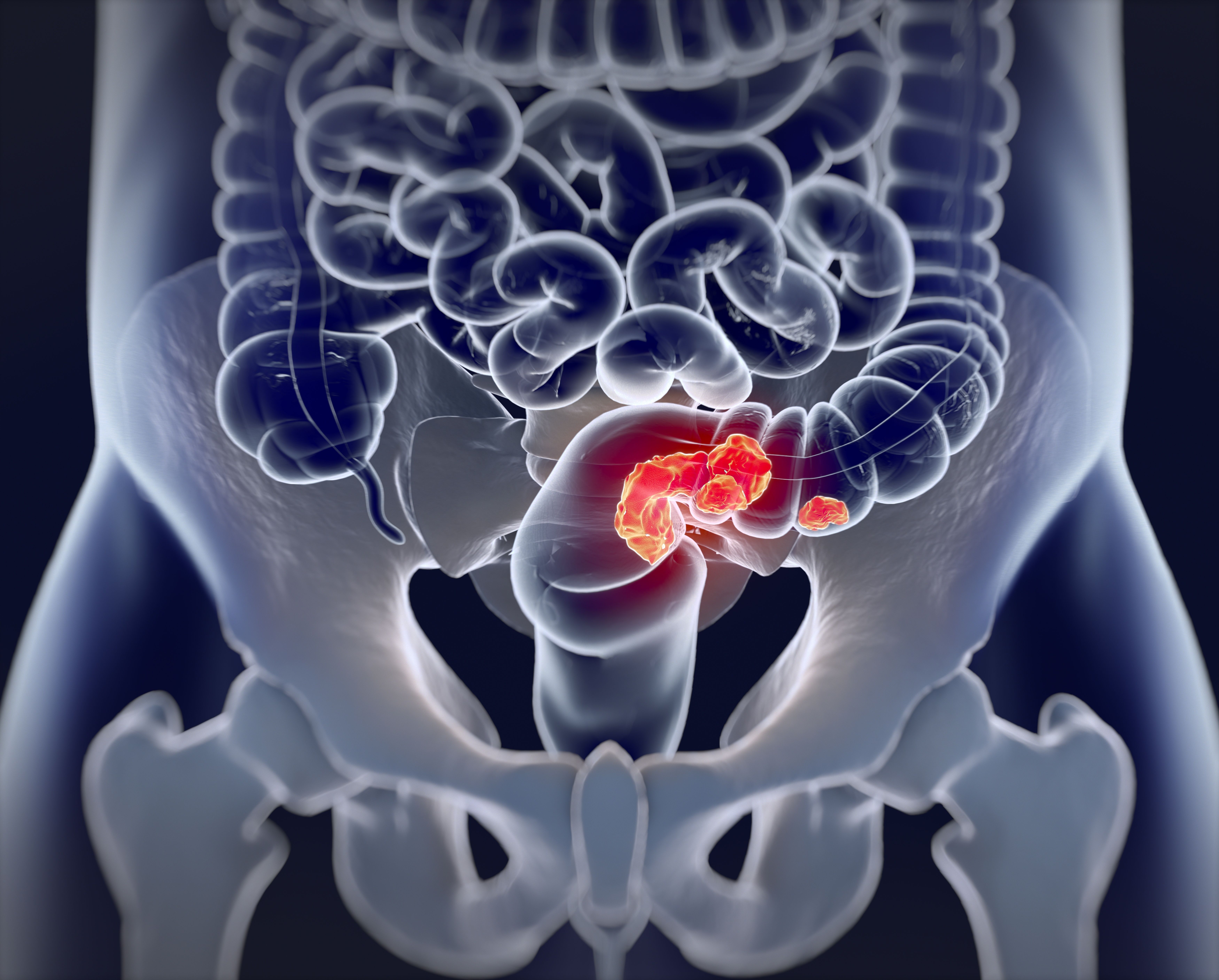

Abdominoperineal resection (APR), sometimes called the Miles procedure or abdominoperineal excision, is a radical surgical operation that removes the rectum, anal canal, and frequently a portion of the sigmoid colon, necessitating the creation of a permanent end colostomy. This surgery is typically reserved for low rectal cancers lying very close to or involving the anal sphincter complex, where sphincter-sparing surgery is not safe or feasible.

Originally devised by Sir William Ernest Miles in the early 20th century, APR became the standard of care for distal rectal cancer because it combined abdominal and perineal approaches to achieve wide excision and reduce local recurrence. Over time, surgical innovation has refined the technique and introduced alternative or adjunctive approaches, such as extralevator APR (ELAPE) and minimally invasive (laparoscopic, robotic) methods.

Although APR remains indispensable for certain patients, it is associated with significant morbidity, long recovery, and profound life changes (due to a permanent stoma and potential functional sequelae). Thus modern colorectal oncology emphasizes multidisciplinary planning, patient counseling, and exploring whether sphincter-sparing alternatives may be viable.

Causes and Risk of Abdomino Perineal Resection Of Rectum

Because APR is a treatment rather than a disease, in this section "indications" (when APR is chosen) and relevant risk/selection criteria are discussed.

Indications for APR

-

Low rectal cancer: Tumors in the distal third of the rectum, particularly when very close to (or invading) the anal sphincter or levator ani muscles, making safe margins with sphincter preservation impossible.

-

Anal cancer or recurrent disease: In cases where chemoradiotherapy fails or recurrence occurs in the anorectal region not amenable to local excision.

-

Recurrent rectal cancer: After prior therapy, when a less radical surgery would risk incomplete resection.

-

Complex benign anorectal pathology (rare): For example, refractory Crohn's disease of the anal region, complex fistulae, or severe radiation injury where sphincter-sparing repair is not durable.

Selection Criteria & Risk Factors

Not every patient with low rectal cancer is automatically a candidate for APR-there are many considerations:

-

Tumor extension and proximity to sphincters/levator muscles: If imaging shows the tumor is too close or invading essential structures, APR may be safer oncologically.

-

Preoperative sphincter function and continence status: If the patient already has poor sphincter control, preserving the sphincter may lead to poor quality of life.

-

Patient comorbidities: APR is a major procedure; cardiovascular, pulmonary, nutritional status must be favorable.

-

Neoadjuvant therapy response: Tumors often receive preoperative chemoradiotherapy to shrink them and improve margin clearance; the degree of response may influence whether APR is needed.

-

Oncologic safety considerations: The surgeon must ensure a clear circumferential resection margin (CRM), avoid intraoperative tumor perforation, and achieve adequate lymph node harvest. Some surgeons prefer extralevator APR (ELAPE) to reduce positive CRM and perforation risk, albeit with increased perineal defect.

-

Patient preference and quality-of-life impact: Because APR leads to a permanent colostomy and can carry functional/sexual/urinary side effects, a fully informed decision is critical.

A 2020 review of patient selection and outcomes underscores that, despite improvements in neoadjuvant therapy and surgical technique, a nontrivial proportion of patients still require APR owing to tumor anatomy or margin constraints.

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms Signs

Since APR addresses a disease (usually rectal cancer) rather than causing symptoms itself, here we describe the symptoms and signs typical in patients who ultimately undergo APR (i.e., those with low rectal / anal malignancy).

Common presenting symptoms:

-

Rectal bleeding: Fresh blood in stool or mixed with feces.

-

Change in bowel habits: Diarrhea, constipation, narrowing of stool caliber ("ribbon stool"), alternating patterns.

-

Tenesmus / urgency / incomplete evacuation feeling.

-

Anal or rectal pain / discomfort, especially with more advanced disease or when tumor invades surrounding structures.

-

Mucus or purulent discharge, especially if tumor ulcerates or there is secondary infection.

-

Obstructive symptoms: In advanced lesions, partial obstruction may cause abdominal pain, distension, constipation, cramping.

-

Weight loss, fatigue, anemia: Chronic blood loss, systemic effects of cancer.

-

Palpable mass on digital rectal exam: A tumor may be felt in the distal rectum or anal canal.

-

Perianal skin changes or ulceration: If the lesion involves or spreads to the anorectal skin.

Symptoms may vary in severity, and early lesions can sometimes be asymptomatic and detected on screening colonoscopy or imaging.

Diagnosis of Abdomino Perineal Resection Of Rectum

Before APR is considered, rigorous diagnostic evaluation is required, both to confirm malignancy and to stage the disease for surgical planning.

Clinical & Endoscopic Assessment

-

History & physical exam: Duration, nature, associated symptoms, constitutional signs.

-

Digital rectal examination (DRE) and proctoscopy / rigid sigmoidoscopy: to palpate and directly visualize the lower rectum / anal canal.

-

Colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy: locate lesion, assess proximal colon, and take multiple biopsies to confirm histopathology (tumor type, grade).

Imaging & Staging Workup

-

Pelvic MRI (high-resolution): to assess local tumor extent, involvement of mesorectum, levator muscles, sphincters, and possible extramural spread.

-

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of chest, abdomen, pelvis: to evaluate for distant metastases (lungs, liver, nodes).

-

Endorectal ultrasound (ERUS): for early tumors, to define depth of invasion and nodal status (often limited when tumor is low or bulky).

-

PET-CT (in selected cases) to detect occult metastases or multifocal disease.

Laboratory & Biomarker Testing

-

Complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, coagulation profile.

-

Tumor marker CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) baseline (not diagnostic, but useful for follow-up).

-

Baseline nutrition, electrolytes, viral status, etc.

Preoperative Multidisciplinary Review & Planning

-

Discussion in a tumor board / multidisciplinary team: colorectal surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, radiologist, pathologist, stoma therapist.

-

Decision about neoadjuvant (preoperative) chemoradiotherapy to shrink tumor and improve margin control.

-

Stoma site marking and counseling by a stoma nurse.

-

Assessment of patient fitness (cardiopulmonary, nutritional) and optimization.

A recent retrospective study in T4 low rectal cancer patients considered the use of post-neoadjuvant / "response" MRI for surgical planning versus pretreatment MRI, and found that pathological circumferential margin positivity remained a concern, emphasizing the need for careful imaging-based planning.

Treatment Options: APR Procedure & Alternatives

This is the core of the content - details of surgical technique, variations, adjunct therapy, and when alternatives may apply.

Standard APR Surgical Technique

-

Anesthesia & Preparation

-

General anesthesia, patient in lithotomy / modified Lloyd-Davis / low lithotomy position for perineal access.

-

Preoperative antibiotics, bowel prep per protocol.

-

The stoma site is already marked.

-

-

Abdominal Phase

-

Midline laparotomy (or laparoscopic/robotic ports).

-

Mobilization of descending colon and sigmoid, ligation of inferior mesenteric vessels (as per oncologic plan).

-

Total mesorectal excision (TME): the mesorectal envelope is dissected down to the pelvic floor, preserving autonomic nerves when feasible.

-

Dissection continues to the level required, down to the level of the pelvic floor / levators.

-

-

Perineal Phase

-

A perineal incision is made around the anus / perineum.

-

Dissection of the anal canal, external and internal sphincters, and levator ani as needed.

-

Removal of the distal specimen (colon + rectum + anus + mesorectum).

-

Closure of the perineal wound (often challenging due to dead space).

-

-

Colostomy Creation

-

The proximal colon is matured as a permanent end colostomy in the abdominal wall.

-

-

Wound Closure & Drainage

-

Drains may be placed.

-

Layered closure of abdominal and perineal wounds; sometimes reconstruction (flap, mesh) for the perineal defect.

-

Variations & Innovations

-

Laparoscopic / Robotic APR: Minimally invasive approach to the abdominal phase; advantages include reduced blood loss, shorter hospital stay, faster recovery. A 2025 meta-analysis confirmed advantages for laparoscopic APR over open (less intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospitalization, fewer complications); earlier series also support laparoscopic APR's safety and efficacy.

-

Transperineal Minimally Invasive Surgery (TpMIS): A new hybrid technique combining laparoscopic abdominal dissection with minimally invasive perineal dissection, which in early reports reduced perineal wound infections, blood loss, urinary dysfunction, and shortened hospital stay.

-

ELAPE (Extralevator APR): A more radical version of APR in which a wider excision of the levator muscles and more cylindrical resection is done to improve clearance and reduce circumferential margin positivity or perforation. The downside is a larger perineal defect and potentially worse wound healing.

-

Flap Reconstruction at Perineum: To minimize perineal wound complications, muscle or myocutaneous flaps (e.g. vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM), gracilis, gluteus, ALT (anterolateral thigh) flap) may be used to buttress or fill dead space. A 2022 study showed a 15% wound complication rate using non-abdominal wall flaps, with the ALT flap having lower complication rates (~9.3%) .

-

Staged or hybrid approaches: In selected or high-risk patients, less radical surgery or staged resections may be considered.

Adjunctive Therapies

-

Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy (CRT): Administered before surgery to shrink tumor, downstage disease, reduce local recurrence, and make radical surgery more effective.

-

Adjuvant Therapy: Postoperative chemoradiation or chemotherapy depending on pathologic findings - nodal positivity, margin status, tumor features.

-

Supportive & Prehabilitation Measures: Nutritional support, physiotherapy, smoking cessation, optimization of medical comorbidities prior to surgery.

Alternative Options When APR May Be Avoided

-

Low Anterior Resection (LAR) / Sphincter-sparing resections (if tumor location and anatomy permit).

-

Intersphincteric Resection (ISR) for ultra-low tumors when partial sphincter sacrifice is feasible but patient continence can be preserved.

-

Local excision / transanal excision for small early-stage tumors.

-

Palliative surgery in unresectable cases (e.g. bypassing obstruction).

-

Nonoperative management / watch-and-wait in highly selected cases with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy (used increasingly in research settings).

-

A recent study comparing Low Hartmann's Procedure (LHP) versus APR for low rectal cancer found a comparable rate of major complications, though minor complications were more frequent in LHP.

In practice, the surgeon and multidisciplinary team weigh all options and choose the operation best aligned with disease control and patient functional outcomes.

Prevention, Perioperative Planning & Management

While APR is not exactly a "preventable" procedure, much of the success and reduced complication rate relies on preparation, prevention of complications, and optimal management before, during, and after surgery.

Preoperative / "Prehabilitation"

-

Medical optimization: Correct anemia, manage comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, cardiac/pulmonary disease).

-

Nutritional support: If malnourished, provide supplements or nutritional interventions.

-

Smoking cessation, alcohol reduction: Improves wound healing and reduces pulmonary complications.

-

Physical conditioning / physiotherapy: Improve baseline functional status.

-

Bowel preparation and prophylactic antibiotics according to institutional protocols.

-

Stoma counseling and marking: Ensure patient understands and is psychologically prepared for living with a permanent colostomy.

-

Psychological counseling and informed consent: Address expectations, risks, life changes (quality of life, sexual/urinary changes).

-

Multidisciplinary planning: Surgeons, oncologists, stoma therapists, nutritionists, anesthesiologists coordinate.

Intraoperative Strategies to Prevent Complications

-

Careful surgical technique to avoid tumor perforation, ensure negative margins (especially circumferential margins).

-

Maintain good hemostasis, gentle tissue handling.

-

Preserve autonomic nerves if oncologically safe to reduce urinary/sexual side effects.

-

Use of flap reconstruction to fill perineal dead space and reduce wound complications in high-risk cases.

-

Adequate drainage of pelvic/perineal spaces.

-

Tension-free, layered wound closure techniques with attention to tissue perfusion.

-

Minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic, robotic, TpMIS) when appropriate to reduce trauma.

Postoperative & Early Recovery Management

-

Pain control: multimodal analgesia, regional blocks or epidural if available.

-

Early mobilization and respiratory physiotherapy to reduce pulmonary complications.

-

Wound care monitoring: attention to perineal and abdominal wound healing, drain management, signs of infection.

-

Stoma care education and monitoring: assess stoma output, skin integrity around stoma, appliance fitting.

-

Diet progression: start with liquids, then soft diet, advancing as tolerated; monitor bowel function and hydration.

-

Close surveillance for complications: bleeding, abscess, anastomotic leaks (if any), urinary retention, DVT/PE.

-

Laboratory monitoring and imaging as needed.

-

Psychosocial support and counseling, especially adjustment to life changes.

Long-Term Management & Surveillance

-

Oncologic follow-up: periodic imaging, colonoscopic surveillance of remaining colon, measurement of tumor markers (e.g., CEA) per protocol.

-

Monitoring stoma-related issues: skin irritation, parastomal hernias, stoma prolapse or stenosis, revision if needed.

-

Management of functional sequelae: urinary dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, perineal pain.

-

Physical rehabilitation and lifestyle counseling: exercise, diet optimization, weight control.

-

Psychological support, stoma support groups: many patients adapt well over time with guidance.

A risk-factor model for postoperative complications emphasizes that robust perioperative planning and risk stratification are key to reducing morbidity in colorectal surgery.

Complications & Their Management

Because APR is a radical surgery, complications - both in early and late phases - are relatively common. Patients should be informed of risks, and surgeons must aggressively monitor and manage issues.

Early / Perioperative Complications

-

Bleeding / hemorrhage (intraoperative or postoperative)

-

Infection / surgical site infection (abdominal or perineal)

-

Perineal wound dehiscence / delayed healing / perineal sinus / nonhealing wounds: one of the most frequent challenges.

-

Pelvic abscess or fluid collection

-

Urinary dysfunction / retention / bladder injury, especially with pelvic dissection

-

Venous thromboembolism (DVT / pulmonary embolism)

-

Respiratory complications (atelectasis, pneumonia)

-

Cardiac events (e.g. myocardial infarction) in susceptible patients

-

Other general surgical risks: anastomotic leaks (if adjunct resections or bowel reconnections), ileus, wound hernias.

In a series of 306 flap reconstructions after laparoscopic or robotic APR, a wound complication rate of 15 % was reported; non-abdominal wall flap reconstructions such as ALT had favorable complication profiles.

Late / Long-Term Complications

-

Perineal hernia: abdominal contents may herniate through the perineal defect later.

-

Stoma complications: parastomal hernia, prolapse, retraction, obstruction, skin irritation or breakdown.

-

Sexual dysfunction / genitourinary dysfunction: nerve injury may lead to erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory disturbance in men; dyspareunia, vaginal changes in women.

-

Local recurrence of cancer, especially if margins were positive or intraoperative perforation occurred.

-

Chronic perineal sinus or wound issues

-

Psychosocial impact / quality-of-life reduction: body image, stoma adjustment, depression, social isolation.

A 2025 study of prognosis and quality-of-life in patients undergoing APR versus low anterior resection reported that APR was associated with slightly worse role and physical functioning at 3 years; however, intensified chemoradiotherapy protocols may mitigate local recurrence risk differences.

Other reviews of quality of life in rectal resection patients show that domains most impacted include bowel function (incontinence, frequency), urinary/sexual function, body image, and psychosocial well-being.

Risk Factors Increasing Complications

-

Prior radiation therapy, which impairs tissue healing and vascularity

-

Large perineal defect and tension on closure

-

Poor nutritional status, diabetes, smoking, obesity

-

Prolonged operative time or intraoperative contamination

-

Inadequate drainage, poor wound technique

-

Use of wider resection (ELAPE) may increase wound complication risk

Management & Mitigation

-

Prompt recognition and treatment: infection gets antibiotics and drainage; dehiscence may require reoperation or vacuum-assisted closure.

-

Flap reconstruction or muscle flaps (VRAM, gracilis, ALT) for difficult perineal defects.

-

Stoma revision or repair for complications such as prolapse or hernia.

-

Sexual/urinary rehabilitation: referral to urology / sexual medicine, medications, pelvic rehabilitation.

-

Close oncologic surveillance for recurrence, with early intervention.

-

Psychosocial support and counseling to address adaptation and quality-of-life issues.

A 2023 study on salvage APR (for persistent disease) indicated worse survival outcomes compared to APR done for recurrent disease, underlying the importance of appropriate timing and patient selection.

In another recent paper, the impact of etiology (e.g. infectious causes) was examined: short-term outcomes in patients undergoing APR with ALT flap reconstruction were worse in cases with underlying infectious pathology, reinforcing the need to tailor reconstructive planning to underlying disease.

Living with APR: Adaptation, Quality of Life Long-Term Outlook

Undergoing APR results in fundamental changes to bowel function, body image, and daily life. While the surgery is life-saving or life-extending, the post-surgical phase requires adaptation, support, and proactive management.

Adapting to a Permanent Colostomy

-

Stoma care training: emptying, changing appliance, skin hygiene, preventing leaks.

-

Choosing the right stoma appliance and accessories: see-through pouches, filters, convex rings, skin barriers.

-

Diet, hydration, and avoiding blockages: educate about foods that increase gas or risk obstruction; chew well; hydration helps stoma output.

-

Monitoring stoma output and warning signs: unusually high or low output, bleeding, stoma retraction, peristomal skin irritation.

-

Addressing stoma complications: skin irritation, parastomal hernias, prolapse or stenosis may require surgical or conservative management.

Functional & Physical Rehabilitation

-

Gradual return to physical activity (walking, light exercise), avoiding heavy lifting for an initial period.

-

Pelvic floor and core strengthening if residual musculature is preserved.

-

Nutritional counseling and maintaining healthy body weight.

Psychosocial & Emotional Adjustment

-

Counseling for body image changes, self-esteem, social interaction, intimacy and sexual concerns.

-

Peer support groups or stoma support networks can offer practical tips and emotional backing.

-

Open communication with family/caregivers about adjustments and expectations.

Chronic Health Monitoring & Follow-Up

-

Regular surveillance for cancer recurrence (imaging, labs, colonoscopy of remaining colon).

-

Routine visits with colorectal surgeon, oncologist, stoma therapist.

-

Monitoring and managing long-term complications (urinary, sexual, hernias).

-

Maintaining healthy lifestyle: diet, exercise, avoiding smoking, staying updated with vaccinations, etc.

Prognostic Outlook & Quality-of-Life Trends

-

Long-term outcomes depend heavily on pathologic stage, margin status, nodal involvement, and recurrence risk.

-

Some comparative data suggest APR patients may have worse local recurrence and survival compared with low anterior resection (LAR) in historical series-though confounding factors (tumor location, biology) may drive the difference.

-

A 2024 study on prognosis and QoL found that after 3 years, role and physical function were modestly lower in APR patients compared to LAR patients, though modern intensified chemoradiotherapy may lessen the difference in recurrence risk.

-

Many patients adapt well over time; quality-of-life scores often improve after the initial postoperative period as patients adjust.

-

Among rectal cancer patients broadly, QoL domains most affected relate to bowel function, sexual/urinary functioning, and body image.

Overall, with proper support, rehabilitation, and monitoring, many APR patients can lead active, meaningful lives, albeit with adjustments.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Abdomino Perineal Resection Of Rectum

1. What is Abdominoperineal Resection (APR)?

Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) is a complex surgical procedure used primarily to treat

rectal cancer located in the lower part of the rectum or the anal

canal. The procedure involves the removal of the rectum, anus, and surrounding

tissue. The goal is to eliminate cancerous cells from the rectum while

ensuring that the margins around the tumor are clear to prevent recurrence. During the

surgery, the anus and rectum are removed, and a permanent

colostomy is created. This means that the waste will exit the body through

an opening in the abdomen, which leads to the creation of a colostomy

bag.

This surgery is typically recommended when the cancer is located too low in the rectum

to preserve the anal sphincter muscles that control bowel movements.

2. Why is Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) performed instead of other surgical treatments?

APR is recommended when the tumor is located near the anal canal and

cannot be removed through less invasive methods like Low Anterior Resection

(LAR), which aims to preserve the anus. In cases where the tumor is close

to or involves the sphincter muscles, or when it's not possible to

achieve clear surgical margins with other methods, APR becomes the best option.

Additionally, rectal cancer with spread to surrounding tissues (such as

lymph nodes) or recurrent cancer may require APR. The procedure also offers the best

chance to fully remove the tumor and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence.

Ultimately, the decision for APR is made based on the location of the cancer, its stage,

and other factors like the patient's general health and whether the cancer has spread.

3. What are the steps involved in the Abdominoperineal Resection surgery?

Abdominoperineal resection involves two main parts:

-

Abdominal Incision: The surgeon makes an incision in the abdomen to access the rectum and sigmoid colon. The colon and rectum are removed along with any surrounding tissue that may have been affected by the tumor.

-

Perineal Incision: Another incision is made in the perineum (the area between the anus and the genitals) to remove the remaining rectal tissues and anus.

After the rectum is removed, the remaining portion of the sigmoid colon is brought through the abdominal wall to create a colostomy. A stoma (an opening in the abdomen) is created, and a colostomy bag is attached to collect waste.

The surgery may take between 4 to 6 hours depending on the complexity of the case and whether any complications arise during the procedure. The patient is closely monitored for bleeding or infection, which are common risks associated with such major surgeries.

4. Is Abdominoperineal Resection considered a major surgery?

Yes, Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) is considered a major surgery due

to its complexity and the significant physical changes it brings to the body. This

surgery requires general anesthesia and involves both abdominal

and perineal incisions, which can take a toll on the body. Recovery can be

lengthy, and patients typically require a hospital stay of 7-10 days

after the surgery. Postoperative care is crucial to monitor for complications such as

infection, bleeding, or issues with the newly created colostomy.

Patients may experience discomfort, pain, and difficulty with mobility

in the days following the surgery, and it will take several weeks to

months to fully recover.

5. What is a colostomy, and why is it needed after APR?

A colostomy is a surgically created opening in the abdomen that allows

waste to leave the body. Since the rectum and anus are removed during

APR, there is no longer a natural route for waste elimination. As a result, a colostomy

is necessary for waste to exit the body.

During APR, a portion of the sigmoid colon is brought through the

abdominal wall to form the stoma. A colostomy bag is then attached to

the stoma to collect waste.

The colostomy is usually permanent, and patients will need to learn how to care for the

stoma and manage the colostomy bag effectively. While this may require some adjustment,

many people are able to live full and active lives after colostomy surgery with proper

care.

6. What are the risks and complications associated with APR surgery?

As with any major surgery, Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) carries potential risks and complications, including:

-

Infection: A risk at both the abdominal and perineal incisions.

-

Bleeding: May occur during or after surgery.

-

Bowel dysfunction: A new colostomy can lead to changes in bowel function, requiring long-term adjustments.

-

Urinary or sexual dysfunction: In rare cases, the surgery can affect the bladder or sexual organs due to proximity to nerves.

-

Blood clots: Can form in the legs (deep vein thrombosis) and travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism).

-

Stoma-related issues: Issues like stoma prolapse or leaks may arise and require further management.

-

Wound healing problems: In some cases, particularly in older patients or those with poor nutrition, wound healing may be delayed.

7. What is the typical recovery process after APR surgery?

The recovery process after Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) can be challenging, requiring patience and medical support. Some key stages of recovery include:

-

Hospital Stay: Most patients will stay in the hospital for 7-10 days to monitor for complications and manage pain.

-

Colostomy Care: One of the most important aspects of recovery is learning to manage the colostomy. A nurse or stoma therapist will provide guidance on caring for the colostomy bag, emptying it, and managing skin around the stoma.

-

Pain Management: Pain is common post-surgery and can be managed with medication. Patients will be closely monitored to ensure pain is well-controlled.

-

Diet: The first few days after surgery will involve a liquid diet, gradually progressing to soft foods as bowel function returns.

-

Mobility: Patients will be encouraged to start moving as soon as possible to reduce the risk of blood clots and improve overall healing.

Patients are generally able to return to normal daily activities after 6-8 weeks, although full recovery may take up to 6 months.

8. Will I need chemotherapy or radiation therapy after APR?

In many cases, chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be recommended after APR surgery, especially if the cancer was advanced or spread to surrounding tissues. These treatments help destroy any remaining cancer cells and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence.

-

Chemotherapy is commonly used for rectal cancer that has spread to lymph nodes or other organs.

-

Radiation therapy may be used to shrink the tumor before surgery or to treat any residual cancer cells after surgery.

Your oncologist will tailor the treatment plan based on the stage and type of cancer, as well as your overall health.

9. How will APR surgery affect my quality of life?

While APR surgery does significantly change bowel function and necessitate the use of a colostomy, many patients are able to lead normal, fulfilling lives after recovery. Some adjustments will be needed, particularly regarding the care of the colostomy bag and dietary modifications.

-

Psychological impact: The changes associated with APR can have a psychological impact, and some patients may experience anxiety, depression, or a sense of loss.

-

Physical adjustment: Patients may need to adjust their physical activity level, particularly avoiding heavy lifting and straining until fully recovered.

-

Social impact: Some patients may feel self-conscious about the colostomy bag. Support groups and counseling can be beneficial for emotional support and practical advice.

With the right support and care, patients can often return to work and resume most of their normal activities within a few months.

10. What is the long-term outlook after Abdominoperineal Resection?

The long-term outlook after Abdominoperineal Resection (APR) depends on factors such as the stage and grade of the cancer, the patient's overall health, and adherence to follow-up care.

-

Cancer-free survival: If the surgery successfully removes all cancerous tissue and adjuvant treatments (such as chemotherapy or radiation) are effective, the patient can live cancer-free for many years.

-

Regular follow-up: Follow-up appointments, including imaging tests and colostomy checks, are essential for detecting any signs of cancer recurrence or complications early.

-

Ongoing care: Even with a colostomy, many patients live full, active lives, though they will need regular monitoring and adjustments to their care.