Introduction to Achilles Tendon Repair

Abdomino-perineal resection (APR), also known as the Miles procedure, is a radical surgical operation that involves the removal of the rectum, anal canal, and surrounding tissues. A permanent colostomy (an opening in the abdominal wall through which waste is diverted into a bag) is created, as the anal sphincter is removed with the rectum. This procedure is most commonly performed for rectal cancers located near or involving the anal sphincter, where sphincter-preserving surgeries (such as low anterior resection) are not feasible.

Why is APR Performed?

The primary goal of APR is to provide oncological control and remove tumors in low rectal or anal canal cancers, especially when other resection techniques are not possible. Low rectal cancers (defined as cancers located within 5 cm of the anal verge) that invade the sphincter complex or the pelvic floor often cannot be safely treated with sphincter-preserving surgeries. In these cases, APR remains the gold standard.

However, with advancements in neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the need for APR has been reduced, as many low rectal cancers can now be treated by preserving the sphincter. APR is still essential in cases of extensive tumor invasion where sphincter preservation would compromise the patient's safety or oncological outcome.

Key Indications for APR

-

Low rectal adenocarcinomas or cancers located too close to the anal sphincter or pelvic floor, which would result in poor functional outcomes with sphincter-preserving surgeries.

-

Invasive anal cancers (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma) that are not amenable to chemoradiation or are recurrent after previous treatments.

-

Extensive pelvic cancers or cases of trauma or congenital conditions causing irreparable damage to the anal sphincter or rectal wall.

Despite advancements, APR remains a crucial procedure in certain scenarios to ensure complete tumor removal and optimal oncologic outcomes. Surgery is often performed in a multidisciplinary setting, including surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and stoma care nurses.

Causes and Risk Factors for Achilles Tendon Repair

Radiotherapy (radiation therapy) is a common treatment for cancer, but it can produce a variety of symptoms and signs due to its effects on both cancerous and healthy cells. Common symptoms and their severity depend on the area treated, the dosage, and individual patient factors.

Primary Causes for APR: Low Rectal and Anal Cancer

Most commonly, rectal cancer is the leading cause that necessitates an abdomino-perineal resection (APR). It is essential to understand the risk factors that contribute to rectal cancer in general, as these often overlap with those for APR:

-

Age: The risk of developing colorectal cancer increases significantly with age, particularly after 50.

-

Family History: A personal or family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps greatly increases risk, especially in familial syndromes such as Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

-

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Conditions like ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease increase the risk of colorectal cancer. Chronic inflammation in the rectum and colon accelerates cancer development.

-

Genetic Mutations: Inherited mutations such as those in the APC gene in FAP or mutations in MLH1, MSH2 in Lynch syndrome can predispose individuals to early-onset cancer.

-

Dietary Factors: High-fat, low-fiber diets, and high red meat consumption are associated with an increased risk of rectal and colon cancer.

-

Lifestyle Factors: Smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and lack of physical activity increase the likelihood of developing colorectal cancer.

-

HPV Infection: Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a significant risk factor for anal squamous cell carcinoma, which may also necessitate APR if the tumor involves the anal canal and cannot be treated with chemoradiation alone.

Factors Leading to the Need for APR

-

Tumor Location: Rectal cancers located within 5 cm of the anal verge are challenging for sphincter-preserving surgery and often require APR.

-

Tumor Size and Extent: Larger or more invasive tumors that involve the pelvic floor, anal sphincter, or other nearby organs often require APR.

-

Failure of Neoadjuvant Therapy: In cases where chemoradiotherapy (CRT) does not shrink the tumor adequately or there is poor response, APR may become necessary to ensure complete resection.

Symptoms and Signs of Conditions Requiring APR

Rectal Cancer and anal cancers can have varying clinical presentations depending on the tumor's location, size, and extent. Patients requiring APR often present with symptoms directly related to their disease, particularly those with low rectal or anal tumors.

Common Symptoms

-

Rectal Bleeding: The most frequent and earliest symptom, especially with tumors that ulcerate or bleed.

-

Change in Bowel Habits: This includes increased frequency of stools, narrowing of stool caliber (pencil-thin stools), and the sensation of incomplete evacuation (tenesmus).

-

Perineal or Rectal Pain: This may occur in advanced cases, especially if the tumor is infiltrating surrounding tissues or nerves.

-

Anorectal Mass: A palpable mass may be detected on digital rectal examination (DRE), particularly in tumors that are located near the anal canal.

-

Urinary and Sexual Dysfunction: Pelvic tumors may cause urinary retention or sexual dysfunction due to the proximity to pelvic structures.

-

Systemic Symptoms: Weight loss, fatigue, anemia, or unexplained fever can occur with more advanced stages of cancer.

-

Absence of Symptoms: In early or small tumors, patients may be asymptomatic, which makes regular screening essential.

Signs Detected on Physical Examination

-

Digital Rectal Exam (DRE): The first step in the clinical evaluation of rectal tumors. A mass or irregularity in the rectal wall may be palpated.

-

Perineal Inspection: In anal cancers, external examination may reveal ulcers, masses, or skin changes.

-

Imaging Abnormalities: In cases where symptoms suggest cancer but physical exams are inconclusive, CT scans and MRI (particularly rectal MRI) help confirm the diagnosis and staging.

Red Flags for Immediate Referral

-

Persistent rectal bleeding.

-

A palpable rectal mass or abnormal findings on digital rectal exam.

-

Symptoms of obstruction or tenesmus.

-

Family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease.

Diagnosis of Conditions Requiring APR

Conditions requiring abdominoperineal resection (APR) are most commonly diagnosed through detailed clinical and imaging assessment, focusing on malignancies and severe benign diseases affecting the lower rectum and anus. The main indications include low rectal or anal cancers, complex Crohn's disease, refractory fistulas, and selected cases of incontinence or trauma.

Diagnostic Approach for Low Rectal Cancer

-

Colonoscopy:

-

Colonoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosing colorectal cancer. It allows for biopsy of any suspicious lesions and facilitates visualization of the tumor and other potentially synchronous lesions in the colon.

-

-

Imaging Studies:

-

MRI Pelvis: The rectal MRI protocol is crucial for determining tumor involvement with the anal sphincter complex, pelvic floor, and surrounding tissues. It assesses whether the cancer can be removed with sphincter-preserving surgery or whether APR is necessary.

-

CT Abdomen and Pelvis: This imaging modality is used for staging and checking for distant metastases (particularly to liver or lungs).

-

Endorectal Ultrasound (ERUS): In cases where MRI is not available, endorectal ultrasound can be used to assess tumor depth and involvement of the mesorectal fascia.

-

PET/CT: For advanced cases, PET scans may help detect metastasis in lymph nodes or distant organs.

-

-

Biopsy:

-

A biopsy obtained during colonoscopy confirms the histopathology of the tumor (usually adenocarcinoma in rectal cancers). A biopsy from any suspicious perineal or anal masses is used to diagnose anal squamous cell carcinoma.

-

Preoperative Workup

-

Staging: Tumor stage is essential in determining the need for neoadjuvant therapy. This will guide the decision on whether APR is needed or if a sphincter-preserving surgery can be attempted.

-

Multidisciplinary Team: The decision for APR is made by a team of colorectal surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and stoma nurses to provide comprehensive care and make the best choice for the patient.

Treatment Options for Low Rectal Cancer and APR

The treatment options for low rectal cancer depend on the tumor's location, size, and stage. For those patients in whom APR is necessary, there are specific goals and approaches.

Surgical Approach for APR

-

Classic Open APR (Miles' Procedure):

-

The traditional open APR involves a two-stage approach. The first stage is performed through an abdominal incision, where the colon and rectum are mobilized, and the tumor is dissected out. The second stage involves excising the perineal portion of the rectum and anus via a perineal incision. A permanent colostomy is then created.

-

-

Minimally Invasive APR:

-

Laparoscopic APR and robotic-assisted APR are becoming increasingly common for tumors that can be approached laparoscopically. These minimally invasive approaches offer quicker recovery, reduced blood loss, and fewer complications than the traditional open procedure.

-

-

Extended Resections:

-

In some cases, an extralevator abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) is used. This modification of APR involves wider excision of the pelvic floor to obtain clear margins when the tumor extends beyond the rectum. ELAPE is especially helpful for tumors with mesorectal fascia involvement.

-

-

Perineal Reconstruction:

-

The perineal defect left after APR is often closed primarily. However, flap reconstruction (e.g., VRAM flaps) may be necessary for larger defects or in patients with prior radiation.

-

Neoadjuvant Therapy for Rectal Cancer

-

Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation (CRT): Patients with locally advanced rectal cancer often undergo CRT before surgery to reduce tumor size, control local disease, and increase the chance of sphincter preservation. However, for those with tumors located too close to the sphincter, APR is still the recommended approach.

Prevention and Management of Achilles Tendon Injury

Prevention and management of Achilles tendon injuries rely on a combination of lifestyle, exercise habits, early recognition, and structured treatment tailored to the severity of injury. Effective prevention can greatly reduce the risk of strains, tendinitis, and ruptures, while evidence-based management helps restore function and minimize complications.

Prevention of Achilles Tendon Injury

-

Proper Warm-up and Stretching: Ensuring muscles and tendons are warm and flexible before engaging in physical activities reduces the risk of injury.

-

Strengthening Exercises: Eccentric strengthening exercises, which focus on lengthening the tendon under load, are proven to reduce the risk of Achilles tendon injuries.

-

Footwear: Wearing shoes that provide adequate arch support and heel cushioning can help prevent strain on the tendon.

-

Avoiding Overuse: Gradually increasing physical activity levels rather than making sudden jumps in intensity can help prevent overuse injuries.

Managing the Condition Post-Injury

-

Immediate Care (R.I.C.E.): Rest, ice, compression, and elevation are critical immediately following an Achilles tendon injury to reduce swelling and pain.

-

Physical Rehabilitation: For both surgical and non-surgical treatments, rehabilitation is essential for regaining strength, mobility, and function.

Complications of APR and Long-Term Management

Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is a major surgical procedure associated with significant complications and complex long-term management requirements. Perineal wound problems, stoma care issues, and effects on physical and psychological health are common and require concerted management.

Early Complications After APR

-

Wound infections (including perineal wound infections): One of the most common and severe complications after APR, especially when preoperative radiotherapy is used. Prevention includes meticulous surgical technique, appropriate antibiotics, and perineal flap reconstruction when necessary.

-

Urinary and Sexual Dysfunction: Autonomic nerve damage during surgery can lead to urinary retention, and sexual dysfunction (e.g., erectile dysfunction in men, dyspareunia in women).

-

Bowel complications: Post-surgical bowel dysfunction or stoma-related issues like blockage or prolapse can occur.

-

Thromboembolic events: As with any major surgery, DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) are risks, requiring prophylaxis.

-

Pain management: Postoperative pain, particularly in the perineum, is a significant issue, and regional anesthesia or epidural analgesia is often used in the perioperative period.

Long-Term Complications and Management

-

Perineal Hernia: A rare but known complication following APR, where the perineal space may protrude after the surgery. This may require repair with surgical mesh or flaps.

-

Colostomy Care Issues: Patients must adapt to living with a permanent colostomy. Problems include stoma prolapse, parastomal hernia, skin irritation, and blockage.

-

Local Recurrence of Cancer: The recurrence rate for rectal cancer varies, and regular oncological follow-up with imaging, colonoscopy, and CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) monitoring is essential.

-

Psychological Effects: Many patients experience depression, anxiety, or body image concerns due to the permanent stoma. Psychological support, including stoma counseling, is essential to address these issues.

Living with APR: Stoma Care and Lifestyle

Living with a permanent stoma after abdominoperineal resection (APR) requires adjustment, but with proper education, stoma care support, and lifestyle adaptation, most patients can return to a full and active life. Initial challenges typically improve within several months, and ongoing support maximizes comfort and confidence.

Adapting to a Permanent Colostomy

Living with a permanent colostomy can be challenging, but with the right education and support, most patients adjust well. Key considerations include:

-

Stoma Care: Proper care and maintenance of the stoma and surrounding skin are critical. Choosing the correct pouching system and understanding how to prevent leakage is vital.

-

Dietary Adjustments: Post-surgery, patients may need to avoid foods that cause gas, odor, or irregular stool (e.g., high-fiber foods).

-

Physical Activity: Most patients can return to light physical activities, and many can resume their normal routines with time.

-

Sexual Health: With support from stoma care nurses and psychologists, patients can address concerns related to intimacy, sexual activity, and body image. Counseling can help individuals and their partners cope with changes.

Quality of Life and Psychological Support

While there is an initial adjustment period after surgery, studies show that quality of life (QoL) improves significantly with proper education, support, and follow-up care. Most patients adapt to their colostomies, and the fear of having a colostomy is often worse than the reality. Long-term psychological and emotional support is integral in the postoperative phase.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Achilles Tendon Repair

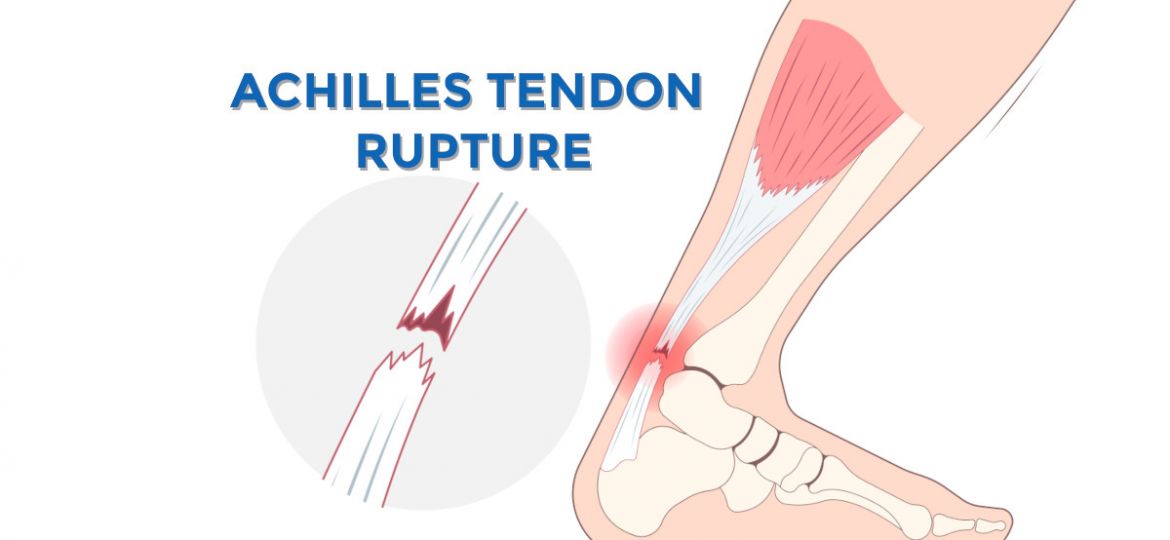

1. What is the Achilles tendon, and what is its function?

The Achilles tendon is a strong band of tissue that connects the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) to the heel bone (calcaneus). It is the largest tendon in the human body and plays a crucial role in walking, running, and jumping by allowing the foot to push off the ground. The Achilles tendon helps with activities that require pushing the foot downward, such as walking, running, and climbing stairs.

2. What causes an Achilles tendon injury?

Achilles tendon injuries often result from sudden or intense physical activity that puts stress on the tendon. Common causes include:

-

Overuse or repetitive strain: Particularly in athletes involved in running, basketball, or tennis.

-

Sudden acceleration or deceleration: Often occurs during sprinting or explosive movements.

-

Tendon degeneration: Over time, the tendon can weaken and become more susceptible to injury, especially in individuals over the age of 30.

-

Trauma: A direct blow or sharp twist can lead to an injury.

Injuries can range from mild strains to complete ruptures of the tendon.

3. What are the symptoms of an Achilles tendon injury?

Symptoms of an Achilles tendon injury may include:

-

Pain and swelling in the back of the ankle, especially after physical activity.

-

A popping or snapping sound at the time of injury, particularly with a rupture.

-

Difficulty walking, running, or pointing the foot downward.

-

Weakness or stiffness in the affected foot or ankle.

-

Bruising or warmth around the tendon.

If the tendon is completely ruptured, the individual may have severe pain, an inability to walk normally, or difficulty standing on tiptoe.

4. What is Achilles tendon repair surgery?

Achilles tendon repair surgery is a procedure performed to repair or reconnect a

torn Achilles tendon. It is often required when the tendon is completely

ruptured or if conservative treatments (such as rest, ice, and physical therapy) do not

provide relief.

The surgery involves making an incision along the back of the ankle, then

suturing the tendon ends back together or, in some cases, using

grafts or tendons to replace the damaged tissue. The goal of the surgery is

to restore function to the foot and reduce the risk of further damage.

5. When is Achilles tendon repair surgery necessary?

Surgery is typically recommended in the following cases:

-

Complete rupture of the tendon: When the Achilles tendon is completely torn and cannot heal properly without surgical intervention.

-

Failure of conservative treatment: When non-surgical treatments like rest, ice, and physical therapy fail to relieve symptoms or restore functionality.

-

Recurrent injuries or weakness: If the tendon remains weak or prone to injury after initial non-surgical treatment.

Your orthopedic surgeon will evaluate the severity of the injury and recommend surgery if it is necessary for functional recovery.

6. What are the different types of Achilles tendon repair surgery?

There are two main types of Achilles tendon repair surgery:

-

Open surgery:

-

The surgeon makes a larger incision along the back of the ankle to access the damaged tendon directly.

-

The tendon ends are stitched together, and if needed, a graft is used to reinforce the repair.

-

-

Minimally invasive surgery (percutaneous repair):

-

In this technique, the surgeon makes small incisions and uses specialized instruments to repair the tendon.

-

It typically results in less tissue damage, faster recovery, and lower risk of infection.

-

7. What can I expect during the recovery process after Achilles tendon repair surgery?

The recovery process typically involves several stages:

-

Immobilization: The foot and ankle are usually placed in a cast or boot for the first 4-6 weeks to allow the tendon to heal.

-

Physical therapy: After the immobilization period, physical therapy begins to restore strength, flexibility, and mobility to the tendon.

-

Weight-bearing: Weight-bearing is gradually introduced once the surgeon deems it appropriate, usually after 6-8 weeks.

-

Full recovery: It can take up to 6-12 months for full recovery, depending on the severity of the injury and the type of surgery performed.

8. What are the risks and complications of Achilles tendon repair surgery?

Although Achilles tendon repair surgery is generally safe, some potential risks and complications include:

-

Infection at the surgical site.

-

Blood clots or deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

-

Re-rupture of the tendon, especially in the first few months after surgery.

-

Tendon stiffness or weakness in the affected foot.

-

Scar tissue formation that may limit ankle mobility.

-

Nerve damage or sensory changes around the ankle.

Most of these risks can be minimized with proper care and following post-operative instructions.

9. Will I need physical therapy after Achilles tendon repair surgery?

Yes, physical therapy is a critical component of the recovery process after Achilles tendon repair surgery.

-

Phase 1 (early recovery): Focus on gentle range-of-motion exercises to maintain flexibility in the ankle and prevent stiffness.

-

Phase 2 (strengthening): As healing progresses, the focus shifts to strengthening exercises to rebuild the tendon's strength and support muscle function.

-

Phase 3 (return to activity): Once strength and mobility have been restored, physical therapy will focus on functional activities and sports-specific training to help return to full activity levels.

Physical therapy can last anywhere from 3 to 6 months depending on recovery progress.

10. How long does it take to fully recover from Achilles tendon repair surgery?

The recovery time varies depending on factors such as the severity of the injury, the surgical approach used, and the individual's overall health. However, the general recovery timeline is as follows:

-

First 6-8 weeks: Immobilization in a cast or boot and limited weight-bearing activities.

-

3-6 months: Physical therapy and gradual return to weight-bearing exercises.

-

6-12 months: Full recovery, where the patient is able to return to sports and high-impact activities.

Even after full recovery, the tendon may remain somewhat weaker than before the injury, and ongoing strengthening exercises may be necessary to maintain optimal function.