Introduction to Acupressure

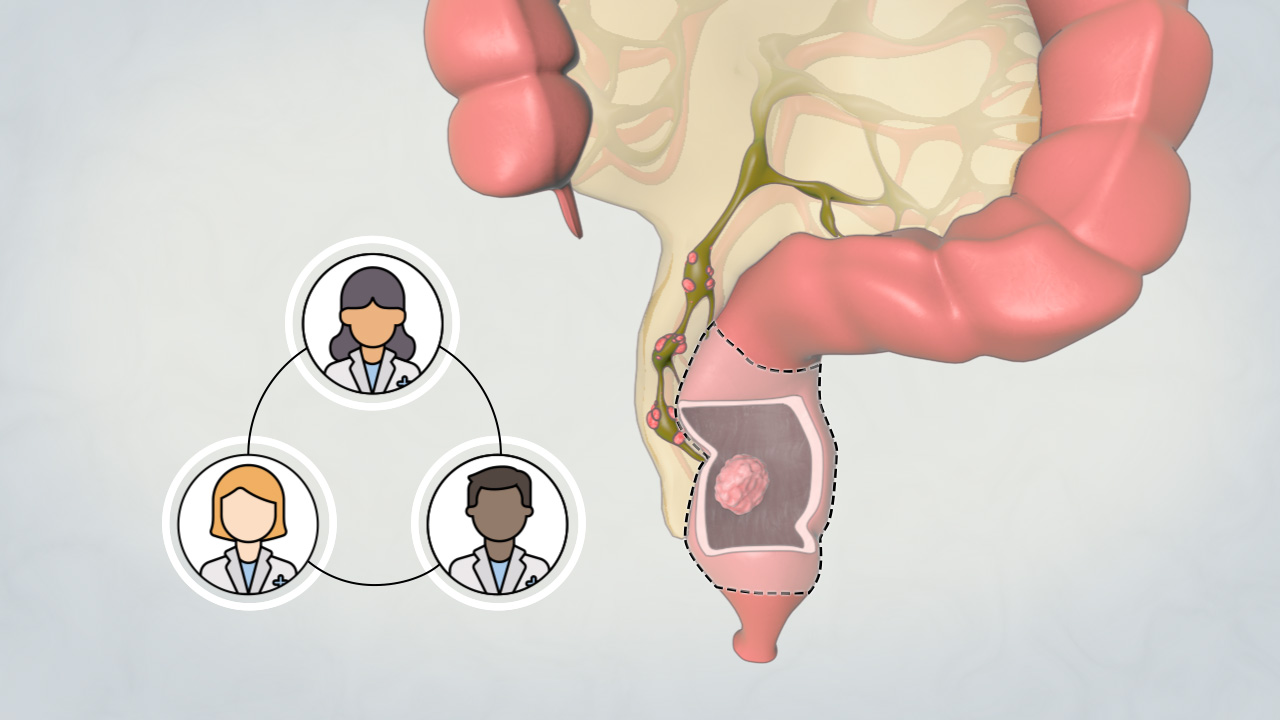

The rectum and distal sigmoid colon are common sites of disease — most notably colorectal cancer but also diverticular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, strictures, and benign tumors. When disease affects a resectable portion of the rectum, surgeons often perform an anterior resection (or low anterior resection if the lower rectum is involved) to excise the diseased segment and restore bowel continuity via colorectal or coloanal anastomosis. Unlike abdominoperineal resection (APR), which necessitates a permanent stoma, anterior resection aims to preserve sphincter function and maintain fecal continuity.

Over the last decades, techniques have refined — use of total mesorectal excision (TME), minimally invasive (laparoscopic, robotic), enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), and functional bowel management protocols have improved outcomes. Still, postoperative bowel dysfunction (collectively termed Low Anterior Resection Syndrome, or LARS) remains common and significantly affects quality of life.

Causes and Risk of Anterior Resection

Anterior resection, particularly low anterior resection (LAR), is a surgical procedure performed to remove a part of the rectum—typically for rectal cancer or benign conditions such as diverticulitis. Although it is a curative surgery, it carries notable risks and potential complications related to anastomosis (bowel reconnection), pelvic anatomy, and nerve injury.

1. Causes / Indications (Why the Surgery Is Done)

Anterior resection is not a disease itself; it's a surgical treatment. The underlying conditions that often lead to anterior resection include:

-

Rectal cancer or rectosigmoid colon cancer (most common indication).

-

Sigmoid colon cancer or lesions located at the distal colon / upper rectum.

-

Diverticular disease / complicated diverticulitis in the sigmoid colon when recurrent or complicated, sometimes requiring resection.

-

Benign tumors / polyps not amenable to endoscopic resection.

-

Inflammatory bowel disease complicated cases (though less commonly).

-

Other local pathology (e.g. strictures, fistulas) in the distal colon/rectum.

In cancer settings, the surgical goal is not simply removal of the diseased segment but also associated lymphadenectomy (removal of lymph nodes) and mesorectal excision (removing the fatty envelope around the rectum) to reduce risk of recurrence.

A variant, low anterior resection (LAR), is often used when the tumor is in the lower rectum but high enough that the sphincter muscles can be preserved.

2. Risk Factors / Patient Factors Influencing Success & Risks

Several patient or disease features raise the complexity, risk, or likelihood of adverse outcomes:

-

Tumor location: Lower / distal rectal tumors are more technically challenging, with higher rates of anastomotic leak and functional disturbance.

-

Male gender and narrow pelvis: anatomically more constrained, raising surgical difficulty and leak risk.

-

Higher blood loss during surgery is associated with higher leak risk.

-

Absence of a diverting stoma (i.e. no temporary diversion) is a risk factor for leak.

-

Radiation therapy / neoadjuvant therapy may impair tissue healing, increase leak risk, and affect functional outcomes.

-

Comorbidities: e.g. diabetes, vascular disease, malnutrition, obesity, smoking, prior abdominal surgery or adhesions.

-

Age: elderly patients may have less reserve, weaker sphincter muscles, and more postoperative functional issues (e.g. incontinence)

-

Preoperative bowel function / sphincter status: patients with weaker baseline sphincter or poorer rectal function are at higher risk of postoperative functional problems.

-

Extent of resection / length of rectum removed: more extensive resection can reduce reservoir effect and predispose to bowel symptoms.

-

Surgical technique, surgeon experience, perioperative care: critical in determining outcomes and complications.

In short: anterior resection is more complex and risky when the tumor is lower, anatomy is challenging, healing potential is compromised, or preoperative function is poor.

Symptoms & Signs (When Anterior Resection Is Indicated)

Because anterior resection is done for underlying bowel disease, the symptoms/signs relate to the disease (cancer, diverticulitis, etc.). Below are typical features that may prompt consideration of resection, plus signs on workup.

1. Clinical Symptoms

Patients considered for anterior resection typically present with:

-

Rectal bleeding (blood in stool, either fresh or darker)

-

Change in bowel habits — e.g. diarrhea, constipation, increased frequency, urgency

-

Tenesmus (feeling of incomplete evacuation)

-

Mucus in stool / discharge

-

Pelvic or rectal pain / discomfort

-

Altered stool caliber (narrowing of stool)

-

Weight loss, fatigue, signs of systemic illness (especially with malignancy)

-

Symptoms of obstruction (if advanced disease) — e.g. cramping, abdominal distension, constipation

-

Recurrent diverticulitis symptoms (in diverticular disease) — pain in left lower quadrant, fever, changes in bowel habits

2. Signs & Physical Examination Findings

-

On digital rectal exam: a palpable mass, irregularity, or nodularity in the rectum

-

Tenderness in the lower abdominal / pelvic region

-

Signs of anemia (pallor) or weight loss

-

Occult blood positive on stool testing

-

On imaging investigation (colonoscopy, CT), suspicious lesions in rectum or sigmoid colon

These symptoms and signs lead to diagnostic evaluation (see next section).

Diagnosis Preoperative Workup

Before performing an anterior resection, a detailed diagnostic and staging workup is essential, particularly in cancer cases, and to plan the surgical approach and anticipate risks.

1. Endoscopic Evaluation & Biopsy

-

Colonoscopy with biopsy of any suspicious lesion — to confirm histopathology (benign vs malignant).

-

Assessment of multiplicity/ synchronous lesions in colon.

2. Imaging & Staging (for cancer cases)

-

CT scan of chest, abdomen, pelvis — to stage and rule out metastases.

-

MRI pelvis (especially in rectal cancer) — to assess depth of tumor invasion, mesorectal involvement, circumferential resection margin, and nodal involvement.

-

Endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) - in selected rectal cancer cases to assess depth of invasion.

-

CT angiography / contrast imaging to evaluate vascular anatomy, especially in planning blood supply to the bowel ends and for anastomosis viability.

-

PET-CT in selected cases to detect metastatic disease.

3. Laboratory & Systemic Workup

-

Full blood count, liver/renal function tests, CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) if colorectal cancer, coagulation profile.

-

Assessment of nutritional status (albumin, prealbumin)

-

Preoperative cardiac, pulmonary risk assessment

-

Bowel preparation, prophylactic antibiotics

4. Preoperative Planning & Risk Assessment

-

Determine whether a diverting stoma (e.g. temporary ileostomy) is needed to protect anastomosis. Many surgeries do this to reduce the risk of leak.

-

Decide between open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted anterior resection depending on tumor location, patient factors, surgeon skill.

-

Plan for total mesorectal excision (TME) if tumor is in lower/mid rectum, to remove mesorectal fat and lymph nodes en bloc, which is known to reduce local recurrence.

-

Evaluate risk of anastomotic leakage, and plan mitigation strategies (stoma, reinforcement, careful surgical technique).

-

Consent discussions: risks (bleeding, leak, infection, stoma, bowel function change, sexual/urinary dysfunction)

Treatment Options Surgical Technique of Anterior Resection

Anterior resection (AR), particularly the low anterior resection (LAR), is the preferred surgical treatment for rectal and sigmoid colon cancers. It aims to remove the cancerous or diseased section of the rectum while preserving the anal sphincter and bowel continuity. The procedure may be done via an open, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted technique depending on tumor location, stage, and patient factors.

1. Treatment Options / Alternatives

-

Local excision / transanal excision: for very early superficial lesions

-

Segmental colectomy / sigmoid resection: for proximal lesions

-

Abdominoperineal resection (APR): when tumors are very low and sphincter cannot be preserved

-

Hartmann's procedure (resection with colostomy and closure of distal stump) in emergency settings or when primary anastomosis is unsafe.

-

Palliative bypass / stenting for unresectable cases

-

Neoadjuvant therapy (chemoradiation) + surgery in rectal cancer protocols

The choice depends on tumor location, stage, patient health, sphincter preservation feasibility, and surgeon judgment.

1. Surgical Technique of Anterior Resection (Step-by-Step)

Below is a generalized overview of how anterior (or low anterior) resection is performed. Variations exist depending on open vs laparoscopic vs robotic.

-

Preparation & anesthesia

- General anesthesia, patient in supine (often Trendelenburg for pelvic access).

- Bowel prep, prophylactic antibiotics. -

Abdominal access

- Open laparotomy or laparoscopic / robotic ports inserted.

- Mobilize colon/sigmoid: mobilize splenic flexure or left colon if needed to allow tension-free reach. -

Vascular ligation and mesenteric dissection

- Ligation of supplying arteries (inferior mesenteric artery, and branches) and division of mesocolon.

- Retract and control blood vessels carefully. -

Rectal mobilization / mesorectal excision (TME)

- Mobilize rectum within mesorectal envelope using sharp dissection in the “holy plane.”

- Preserve pelvic autonomic nerves as much as possible (hypogastric nerves, pelvic plexus). Injury here can cause urinary or sexual dysfunction. -

Tumor resection / margins

- The diseased rectal/sigmoid segment is removed with adequate margins.

- Lymph node removal (regional nodes) is done in cancer cases. -

Anastomosis

- The proximal healthy colon is reconnected to the remaining rectum or anus (colorectal or coloanal anastomosis), often using staplers or hand-sewn technique.

- Leak testing (air or dye) to check anastomosis integrity; if risk, a diverting stoma may be created. -

Stoma (if used) and drainage

- A temporary ileostomy or colostomy may divert fecal stream away to allow the anastomosis to heal safely.

- Drains may be placed in pelvic cavity to monitor for leaks/bleeding. -

Closure & recovery

- The abdominal incision / port sites are closed, patient monitored in ICU or ward, follow post-op protocols.

Minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic, robotic) follow same principles but with smaller incisions, camera guidance, and instrument assistance.

Surgical success depends heavily on tension-free anastomosis, good vascular supply to ends, meticulous technique, and preservation of autonomic nerves.

Prevention Perioperative Management (How to Reduce Risk / Optimize Outcomes)

Prevention and perioperative management for anterior resection focus on minimizing complications (especially anastomotic leakage and low anterior resection syndrome, LARS), optimizing patient outcomes, and promoting faster recovery. This is achieved through a combination of patient preparation, evidence-based surgical techniques, early rehabilitation, and careful aftercare.

1. Preoperative Optimization

-

Smoking cessation

-

Good nutritional status (correct deficiencies, optimize albumin)

-

Control comorbidities (diabetes, cardiovascular disease)

-

Preoperative bowel preparation, prophylactic antibiotics

-

Preoperative evaluation of pelvic anatomy (imaging)

-

Marking stoma site with stoma nurse if diversion is considered

-

Patient education and informed consent covering functional consequences

2. Intraoperative Risk Mitigation

-

Sharp surgical dissection along correct planes (mesorectal plane) to preserve nerves

-

Meticulous hemostasis

-

Adequate vascular ligation preserving collateral blood flow

-

Ensure tension-free and well-perfused anastomosis

-

Routine leak testing of anastomosis, with intraoperative reinforcement or diversion if needed

-

Selective use of diverting stomas to reduce consequences of leaks

-

Gentle tissue handling, minimize traction on nerves and blood supply

3. Postoperative Care & Early Monitoring

-

Early mobilization

-

Bowel regimen (prevent ileus)

-

Monitor for signs of leak (fever, abdominal pain, drainage, peritoneal signs)

-

DVT prophylaxis, fluid and electrolyte management

-

Nutritional support — early feeding as tolerated

-

Delayed reversal of temporary stoma after healing

-

Long-term monitoring for functional adaptation

Complications of Anterior Resection

Anterior resection carries risks, some general to colorectal surgery and some specific to pelvic / rectal operations (including nerve injury and low anterior resection syndrome). Below is a detailed list with incidence ranges, risk factors, detection, and management.

1. Common & Serious Complications

-

Anastomotic leak

- One of the most feared complications.

- In one series: 8.1% leak rate in TME (total mesorectal excision) vs 1.3% in PME (partial mesorectal excision) cases.

- Risk factors: male gender, high blood loss, low anastomosis, no diversion, poor tissue perfusion, prior radiation.

- Recognition: postoperative fever, abdominal pain, peritonitis, elevated inflammatory markers, drainage.

- Management: conservative (antibiotics, drainage) or surgical re-exploration / diversion. -

Postoperative infections (surgical site infection, abscess)

- Incisional infection, pelvic abscess, urinary tract infections, etc. -

Pelvic autonomic nerve injury / urinary and sexual dysfunction

- Due to damage to hypogastric nerves, pelvic plexus, inferior hypogastric plexus during mobilization.

- Consequences: urinary retention, erectile dysfunction, retrograde ejaculation, dyspareunia in women. -

Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS) / Bowel dysfunction

- High prevalence: up to 80% of patients may experience bowel dysfunction including urgency, frequent bowel movements, fecal incontinence, clustering, incomplete evacuation.

- A recent long-term study found 53.4% had major LARS in a cohort of 311 patients ~6.5 years out.

- LARS significantly impacts quality of life. -

Fecal incontinence, urgency, frequency

- Particularly in elderly or patients with weaker sphincter function at baseline. -

Stoma complications (if temporary ileostomy or colostomy used)

- Stoma site infection, prolapse, retraction, hernia -

Bleeding / hemorrhage

- Intraoperative vascular injury or postoperative bleeding -

Ileus / bowel obstruction

- Transient ileus after abdominal surgery is common. -

Urinary complications (retention, bladder dysfunction)

-

Reoperation / surgical re-interventions

-

Local recurrence of cancer (in cancer cases)

- E.g. in a cohort with anterior resection + mesorectal excision: 5-year local recurrence ~9.7%. -

Mortality risk (rare in elective settings, higher in emergency settings or with comorbidities)

Quantitative risk models exist. For example, a prediction model for postoperative complications after LAR includes risks of surgical site infection (excluding leak), anastomotic leakage, UTI, pneumonia, renal failure, etc.

Because many complications interplay (nerve injury + LARS, leak + reoperation), preoperative planning, surgical precision, and postoperative vigilance are essential.

Living with Anterior Resection — Recovery, Function & Quality of Life

After anterior resection, patients must adapt to changes in bowel function, recover physically, cope with complications, and gradually regain quality of life. This section describes typical recovery trajectory, long-term functional expectations, strategies for managing LARS, and patient experience.

1. Recovery Timeline & Functional Progress

-

Hospital stay: often around 7-10 days (varies by open vs minimally invasive).

-

Return of bowel function: gradually over days (may begin with liquids, then soft diet).

-

Stoma reversal (if temporary) often done after 3-6 months, depending on healing and absence of complications.

-

Full recovery: 3-6 weeks for general recovery, but functional bowel adaptation may take many months to years.

-

Long-term follow-up: monitor oncologic outcomes (if cancer), surveillance colonoscopies, supportive care for bowel symptoms.

2. Bowel Function, LARS & Quality of Life

Low Anterior Resection Syndrome (LARS)

-

A combination of symptoms—fecal urgency, incontinence, clustering, frequent bowel movements, evacuatory difficulties.

-

It can have major impact on quality of life, social function, emotional well-being.

-

Longitudinal data show that the prevalence of major LARS declines over time postoperatively; in one study, functional domains like constipation, social/emotional scores improved after ileostomy reversal over years.

-

In qualitative studies, patients describe bowel emptying becoming all-consuming, work and social life disruption, guilt, and sexual/urinary effects.

Other functional outcomes

-

Fecal incontinence / urgency are common, especially in older patients or those with weaker sphincter function.

-

Sexual dysfunction / urinary symptoms: damage to pelvic autonomic nerves can cause urinary retention, bladder dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, retrograde ejaculation, dyspareunia in women.

-

Loss of rectal reservoir capacity: when a large portion of the rectum is removed, its ability to serve as a stool reservoir is diminished, contributing to frequent bowel movements.

Quality of Life

-

Many patients report improvement over time, but symptoms may persist in a substantial subset.

-

In long-term retrospective cohorts, improvements in social, emotional and constipation scores are observed over years.

-

Overall QoL after rectal resection is affected by bowel dysfunction, urinary/sexual problems, pain, and psychological adaptation.

3. Strategies to Manage Bowel Symptoms

-

Dietary adjustments: smaller meals, low-residue diet initially, gradual reintroduction of fiber, avoid irritants (caffeine, spicy foods).

-

Bowel regimen: use of anti-diarrheal agents (e.g. loperamide), bulking agents, fiber supplements, or osmotic agents depending on symptoms.

-

Pelvic floor rehabilitation / biofeedback: retraining muscles, improving control.

-

Transanal irrigation: regular flushing of the lower bowel to prevent clustering or urgency episodes.

-

Sacral nerve stimulation or posterior tibial nerve stimulation (in selected cases) for persistent LARS.

-

Medications for motility / stool consistency

-

Lifestyle adjustments: planning bathroom access, scheduling meals/activities around bowel patterns, modifying work/social life.

-

Psychosocial support: counseling, support groups, coping strategies

4. Special Considerations & Risk Groups

-

Older patients and women may have higher risk of incontinence postoperatively.

-

Pelvic radiotherapy or prior pelvic surgery increases risk of functional complications.

-

Patients with baseline weak sphincter or poor continence need more counseling.

5. Long-term Monitoring & Follow-up

-

Regular colorectal surveillance (e.g. colonoscopy) for recurrence in cancer cases

-

Monitoring and managing late complications (strictures, fistula, recurrence)

-

Ongoing support for bowel, urinary, and sexual function

-

Assessment and management of nutrition, psychological health, and quality of life

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Anterior Resection Surgery

1. What is Anterior Resection Surgery?

Anterior resection is a surgical procedure primarily used to remove cancerous or diseased sections of the rectum or lower colon while preserving the anal sphincter. It is often performed for rectal cancer, diverticulitis, or other rectal diseases.

The goal of the surgery is to remove the affected portion of the bowel and reconnect the healthy ends, maintaining normal bowel function.

2. Who is a candidate for Anterior Resection?

Ideal candidates include patients who:

-

Have rectal or distal colon cancer located away from the anal sphincter

-

Suffer from recurrent diverticulitis or strictures

-

Are in good overall health to undergo major surgery

-

Require removal of diseased bowel while preserving bowel continence

Your surgeon will evaluate factors like tumor location, size, and overall health before recommending the procedure.

3. How is Anterior Resection Surgery performed?

Anterior resection can be performed as open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, or robotic-assisted surgery. The procedure generally involves:

-

Making an incision in the abdomen (or small laparoscopic ports)

-

Removing the diseased portion of the rectum or colon

-

Reconnecting the healthy ends (anastomosis) to restore bowel continuity

-

Sometimes a temporary ileostomy is created to allow healing

The surgery typically takes 2-4 hours, depending on complexity and patient anatomy.

4. What is the recovery process after Anterior Resection?

Recovery varies but generally follows this timeline:

-

Immediate post-surgery: Hospital stay of 5-10 days for monitoring and pain control

-

First 2-4 weeks: Avoid heavy lifting, follow a low-fiber diet, and gradually increase activity

-

4-6 weeks: Most patients resume light daily activities

-

3 months: Normal bowel function and energy levels typically return

Adhering to post-operative care and diet instructions is essential for proper healing.

5. What are the benefits of Anterior Resection Surgery?

Benefits include:

-

Removal of cancerous or diseased tissue

-

Preservation of anal sphincter function, allowing normal bowel movements

-

Reduced risk of recurrence for rectal cancer or diverticulitis

-

Improved quality of life through restored bowel function

The surgery aims to balance disease eradication with maintaining continence.

6. What are the risks or complications of Anterior Resection?

Potential risks include:

-

Bleeding or infection at the surgical site

-

Leakage at the anastomosis site (where the bowel is reconnected)

-

Bowel obstruction or adhesions

-

Temporary or permanent changes in bowel habits

-

Rarely, damage to nerves or surrounding organs

Careful surgical technique and proper post-operative monitoring minimize these risks.

7. Will I need a colostomy after Anterior Resection?

In some cases, a temporary colostomy or ileostomy may be created to allow the bowel to heal safely. This is usually reversed in 6-12 weeks after surgery once healing is confirmed.

Permanent colostomy is rare and typically only required if:

-

The tumor is very low near the anus

-

There is significant bowel disease or complications

Your surgeon will discuss this before surgery.

8. How soon can I return to normal activities after surgery?

-

Light activities and walking: Usually 2-4 weeks after surgery

-

Driving or desk work: Around 4-6 weeks

-

Strenuous exercise or heavy lifting: Typically 8-12 weeks

Following your surgeon's instructions on activity levels is essential for safe recovery.

9. How successful is Anterior Resection Surgery?

Success depends on the underlying condition and patient health:

-

Rectal cancer: Removal of the tumor significantly reduces the risk of recurrence if combined with proper staging, chemotherapy, or radiation when needed

-

Diverticulitis or strictures: Surgical removal of diseased bowel usually prevents recurrence

Most patients achieve good bowel function and quality of life, especially when the anal sphincter is preserved.

10. How should I prepare for Anterior Resection Surgery?

Preparation steps include:

-

Pre-operative medical evaluation, including blood tests, imaging, and colonoscopy

-

Medication review, especially anticoagulants or diabetes medications

-

Bowel preparation with laxatives or enemas before surgery

-

Smoking cessation to improve healing

-

Planning home support during the recovery period

Your surgeon will provide specific pre-operative instructions for optimal outcomes.