Introduction to Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) - the involuntary leakage of urine - is a condition that affects millions of people worldwide and has profound effects on quality of life, from social embarrassment to skin problems, psychological distress, and limitations on daily activities. Among the different types of UI, one of the more challenging to treat is sphincter deficiency-related incontinence (often stress urinary incontinence, SUI, due to failure of the urethral sphincter mechanism). In such cases, one of the most effective long-term solutions is the implantable device commonly called an artificial urinary sphincter (AUS).

An artificial urinary sphincter is a surgically implanted device designed to replicate or augment the function of the natural urethral sphincter - the valve-like muscle that keeps urine in the bladder until a person is ready to void. When properly selected and implanted, the AUS can restore continence (or markedly improve it) in patients who have failed conservative measures and whose incontinence is due primarily to sphincter insufficiency.

Historically, the first implantable devices to manage sphincter incompetence emerged in the 1940s, with the modern AUS design developed in the early 1970s. Over the decades, the AUS has become accepted in urology as the gold standard surgical treatment for severe SUI in men (especially following prostate surgery) and increasingly in carefully selected women.

In this article we will explore the causes and risks that lead to the need for an artificial sphincter, the symptoms and signs patients experience, how diagnosis is made, the range of treatment options (with focus on AUS), prevention and management strategies, possible complications, and what life is like after the implant.

Causes and Risk of Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

To understand when the artificial urinary sphincter becomes relevant, it is important to understand the mechanisms of incontinence and how sphincter deficiency arises.

Mechanism of Continence

In a healthy urinary system, continence is maintained by a coordinated interplay of anatomical structures and neural control:

-

The bladder stores urine under low pressure until a person is ready to void.

-

The urethra is closed by the action of the urethral sphincter (both internal and external sphincters) and is supported by surrounding pelvic floor and connective tissue.

-

When voiding is initiated, neural signals cause the detrusor (bladder muscle) to contract and the sphincter to relax, allowing urine to flow out.

When the sphincter mechanism fails (either from weakness, injury, or loss of neural control), leakage may occur - especially when intra-abdominal pressure rises (coughing, sneezing, lifting). This is known as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In more severe cases, the sphincter may be so deficient that leakage occurs with minimal effort, even at rest.

Causes of Sphincter Deficiency

Some common causes that lead to the need for an artificial urinary sphincter include:

-

Post-prostatectomy or other prostate surgery in men: Radical prostatectomy or surgery for benign prostatic enlargement can damage the external urethral sphincter or its nerve supply. The prevalence of incontinence post-prostatectomy varies widely, reported as up to ~8% or more depending on surgical technique and patient factors.

-

Radiation therapy: Radiation to the pelvis or prostate may lead to tissue fibrosis, reduced urethral blood supply, and sphincter atrophy or dysfunction. Such patients face higher complication or revision risks when considering AUS.

-

Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD): This term is used when the urethral closure mechanism is inherently weak (due to age, trauma, congenital weakness) even if pelvic support is adequate.

-

Prior pelvic surgery: Surgeries such as radical cystectomy, urethral reconstruction, or previous incontinence surgeries may compromise urethral integrity or impair sphincter function.

-

Neurological causes: In patients with neurogenic bladder or spinal cord injury, sphincter dysfunction may contribute to incontinence; although less common as primary AUS indication, it is increasingly being explored.

-

Ageing, obesity, chronic cough, heavy lifting: These factors do not by themselves mandate an AUS but increase the risk of incontinence by placing stress on the pelvic floor and urethral closure mechanisms.

Risk Factors for When AUS Is Necessary

Not everyone with incontinence will need an artificial sphincter - but certain risk factors increase the likelihood of needing an advanced surgical option such as AUS. These include:

-

Moderate to severe leakage (many pads per day, large volumes) despite conservative treatment.

-

Long-standing incontinence (especially >6-12 months) that is significantly impacting quality of life. (Guidelines suggest earlier referral for persistent SUI after prostate surgery)

-

Previous failed incontinence surgery or sling device.

-

Urethral injury, prior radiation, or other anatomical damage making less invasive options less likely to succeed.

In summary: when the urethral sphincter mechanism is irreversibly compromised, and conservative therapies have failed, an artificial urinary sphincter becomes a viable and often preferred surgical option.

Symptoms and Signs Artificial Sphincters For Urinary Incontinence

The signs and symptoms of sphincter-related urinary incontinence (and the indications for an AUS) can vary, but there are characteristic features that warrant evaluation.

Typical Symptoms

-

Leakage of urine during increased abdominal pressure: Sneezing, coughing, laughing, running, lifting heavy objects - the classic sign of stress urinary incontinence (SUI).

-

Large volume leaks or continuous dribbling: In more severe sphincter deficiency, even minimal movements may trigger leakage, or there may be loss of control that leads to dampness or full pads.

-

Frequent pad/diaper usage: Patients may need multiple protective pads per day, constantly changing due to leakage.

-

Night-time leakage: Although more common in urgency incontinence, severe SUI may result in leaks during sleep or while lying down.

-

Perineal or groin skin irritation: Constant dampness may cause skin breakdown, rashes, or infection.

-

Avoidance or alteration of activities: Many patients restrict social outings, travel, exercise, or intimacy due to fear of leakage, embarrassment, or odor.

-

Psychological and emotional toll: Anxiety about incontinence episodes, social withdrawal, depression, impact on self-esteem.

When to Suspect Sphincter Deficiency / Need for AUS

-

If the leakage remains persistent and bothersome, despite pelvic floor exercises, behavioural measures, and possibly medications.

-

If there is a known cause of sphincter injury (e.g., prior prostatectomy, pelvic surgery, radiation).

-

If the patient is using multiple pads daily (e.g., >3-4 pads/day) and still experiencing leakage.

-

If the patient has failed prior incontinence surgery (e.g., sling) and still has significant symptoms.

-

If there are no significant bladder overactivity symptoms (urgency/frequency) dominating the picture but rather a pure stress leakage scenario.

Recognising the symptoms early and referring for specialist assessment can make a difference in outcomes - delaying too long may allow secondary changes (bladder dysfunction, urethral atrophy) that complicate treatment.

Diagnosis of Artificial Sphincters For Urinary Incontinence

A thorough diagnostic work-up is key to determine whether an artificial urinary sphincter is appropriate, to identify any co-existing bladder or urethral problems, and to plan surgery safely.

Clinical Assessment

-

Detailed patient history: Document onset of incontinence, number of pads used daily, triggers of leakage, prior surgeries (e.g., prostatectomy, pelvic radiation), bladder symptoms (frequency, urgency), neurological history.

-

Bladder diary: Recording voiding times, volumes, leakage events, pad changes for 48-72 hours can help quantify severity and pattern.

-

Physical examination:

-

In men: Digital rectal exam, check for prior surgical scars, incontinence maneuvers (coughing while standing).

-

In women: Examination of pelvic floor support, urethral mobility, presence of pelvic organ prolapse, signs of urethral or vaginal surgery.

-

-

Urinalysis/urine culture: To rule out infection, hematuria, which may worsen incontinence or contraindicate surgery.

-

Urodynamic testing: Important in many cases: assesses bladder capacity/compliance, detrusor overactivity, urethral pressure/closure, leak point pressures, residual urine. Especially valuable if mixed incontinence (stress/urgency) or suspected bladder dysfunction.

-

Imaging / endoscopy: May include ultrasonography (bladder wall, post-void residual), cystoscopy (to check urethra, prior surgery or radiation damage) or MRI in complex anatomy.

-

Urethral/urethrogram assessment: Prior urethral procedures or radiation may cause urethral fragility; this affects surgical planning (e.g., choice of cuff placement such as trans-corporal).

Suitability and Pre-operative Counselling

A key part of diagnosis is deciding if an AUS is appropriate. Some considerations include:

-

Ensuring bladder function is adequate. If bladder has poor compliance, uncontrolled overactivity or high residual volumes, an AUS alone may not fix the problem.

-

Ensuring no untreated bladder outlet obstruction or urethral stricture, since placing a cuff around a narrowed urethra increases risks (erosion, retention).

-

Reviewing patient's manual dexterity and cognitive ability: The patient must be able to operate the pump (especially in men) and understand how to use the device, recognize problems, and follow follow-up.

-

Discussing patient expectations: Even after AUS, many patients may still require 0-1 pad/day rather than being completely pad-free. Satisfaction is high, but full "dry all the time" outcome is not guaranteed. For example, meta-analysis data show a "dry" rate around 52% and "social dry" (<1 pad/day>) around 82% in selected men.

-

Surgical risk assessment: Because AUS surgery is not trivial and long-term outcomes are influenced by surgeon experience. For example, at least 200 procedures may be required to reach optimum proficiency.

Timing of Intervention

For men with post-prostatectomy incontinence, guidelines suggest waiting at least 6-12 months to allow for spontaneous recovery of continence before proceeding to AUS in those with moderate symptoms; however, in severe cases earlier intervention may be justified.

In summary, successful outcomes depend on careful patient selection, comprehensive evaluation of bladder and urethral function, realistic expectation setting, and planning for the surgical approach tailored to the patient's anatomy and history.

Treatment Options of Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

This section covers a continuum of treatment approaches - from conservative management to surgical implants, with a detailed focus on the artificial urinary sphincter (AUS).

Conservative / Non-Surgical Treatments

Before moving to implantable devices, many patients will undergo - or should undergo - non-surgical strategies.

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT)

-

An underpinning therapy especially in women or men with mild-to-moderate SUI: supervised physiotherapy, use of biofeedback, electrical stimulation in some cases.

-

The aim is to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles that support the urethra and assist sphincter closure.

Behavioural & Lifestyle Measures

-

Weight loss in obese individuals improves incontinence outcomes.

-

Avoiding/limiting bladder irritants (caffeine, alcohol), timed voiding, bladder training.

-

Treating chronic cough/sneezing (e.g., smoking cessation).

-

Reducing heavy lifting or high-impact activities if they exacerbate leakage.

Absorbent Products & External Devices

-

Pads, diapers, penile clamps (in men) may be used as interim or adjunctive measures.

-

These do not treat the underlying cause but improve quality of life.

Minimally Invasive Surgical Options

-

Male sling procedures: For mild to moderate SUI in men, slings compress or reposition the urethra to improve closure.

-

Urethral bulking agents: Injections under the urethra to enhance urethral coaptation. Their long-term efficacy is variable and often inferior in moderate/severe cases.

-

Adjustable continence devices: Some devices allow adjustment of urethral compression.

However, for moderate to severe SUI due to intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), slings/bulking may not suffice; the implantable AUS often yields superior outcomes. For example a recent study indicated AUS was better than slings for moderate male SUI with acceptable complication rate.

The Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS)

What is an AUS?

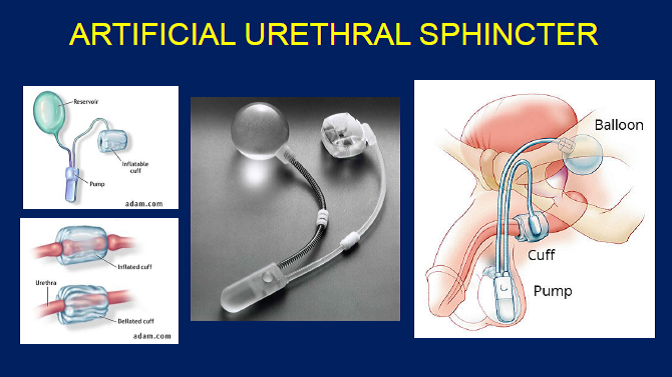

The artificial urinary sphincter is a mechanical, hydraulic device typically composed of three key parts:

-

A cuff that wraps around the urethra (or bladder neck in some women) and exerts pressure to keep the urethra closed.

-

A control pump / activation unit, usually implanted in the scrotum in men (or in the labia/perineum in women) which the patient presses when ready to void.

-

A pressure-regulating balloon/reservoir, typically placed in the retropubic space or abdomen, which holds fluid and establishes the pressure in the system.

When the patient wishes to urinate, he/she squeezes the pump, temporarily reducing cuff pressure and opening the urethra; after voiding, the system automatically re-inflates the cuff and restores continence.

Indications

-

Moderate to severe stress urinary incontinence due to intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) - especially in men after prostate surgery.

-

Cases in women with SUI where other options (slings, pelvic floor training) have failed and anatomy allows. Meta-analysis showed AUS implantation in women had overall continence rate ~72%, though with higher revision/explantation rates.

-

Neurogenic sphincter deficiency in selected patients (e.g., neurogenic bladder + sphincter incompetence) - though outcomes in this group tend to have higher revision rates.

Surgical Procedure Overview

-

Typically performed under general or regional anaesthesia; many centres now perform as outpatient or 1 overnight stay.

-

In men: The cuff is placed around the bulbar urethra, the reservoir in retropubic space, the pump in the scrotum.

-

In women: The cuff may be placed around the bladder neck via vaginal or abdominal approach (less common).

-

After surgery, there is a healing period (often 4-6 weeks) before the device is activated/used.

-

Patient education is delivered on how to operate the pump, what to expect, follow-up schedule.

Outcomes & Efficacy

-

Numerous studies demonstrate high levels of improvement. For example, a meta-analysis found an "overall dry rate" ~52% and "social dry" (≤1 pad/day) ~82% in post-prostatectomy men.

-

A long-term outcomes review of 50 patients (median follow-up 23 months) reported 90% satisfaction, 96% would recommend AUS.

-

For women: A systematic review found 72% continence but revision rate ~22.5% and explant ~17.6%.

-

Recent literature emphasizes that AUS remains the gold standard for severe SUI in men, with very high satisfaction when patient selection is correct.

Recent Developments & Future Directions

-

While the basic design of the AUS has remained largely unchanged for decades, recent work is exploring adjustable cuffs, electronic AUS (eAUS), and refinements in implantation techniques (e.g., trans-corporal cuff placement for fragile urethras) to improve durability and reduce complications.

-

A narrative review covering June 2022-June 2024 highlights innovations and prospective trials in AUS development.

How to Choose Between Options

When deciding between a sling, bulking, adjustable device or AUS, key considerations include:

-

Severity of leakage (pad count, volume).

-

Underlying cause (pure sphincter deficiency vs mixed incontinence).

-

Previous surgeries/radiation (which may reduce success of slings).

-

Patient's manual dexterity and willingness to accept an implantable mechanical device.

-

Surgeon's experience and institutional volume (outcomes are better at high-volume centres)

Post-operative Care & Follow-Up

-

After implantation, the device is typically activated after ~4-8 weeks (depending on healing).

-

Training on pump use: when and how to void, what to expect.

-

Avoid heavy lifting, bicycling, or high-impact activity early on to prevent cuff migration or erosion.

-

At follow-up: check for leaks, residual urine, signs of infection or erosion, device function (via palpation of pump/reservoir) and patient satisfaction.

-

Long-term: Many devices may last ~8-10 years (or more) before revision or replacement may be needed.

Prevention and Management of Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

While an artificial urinary sphincter is a powerful treatment, prevention of incontinence (or prevention of worsening of incontinence) and good management practices before and after surgery enhance outcomes.

Prevention of Incontinence or Progression

-

Encourage pelvic floor muscle training early (especially in women antenatal/postnatal, men pre/post prostate surgery).

-

Lifestyle measures: Maintain healthy weight, treat chronic cough, avoid smoking, limit heavy physical strain.

-

Address modifiable factors: Manage diabetes, avoid constipation (which leads to straining), reduce bladder irritants.

-

Early referral when incontinence persists after prostate surgery (>6 months) or when leakage is severe. Delays may worsen urethral atrophy or bladder dysfunction, reducing success of future implants.

Management Before AUS Implantation

-

Manage bladder dysfunction (urge symptoms, detrusor overactivity) so that post-implant continence is not compromised.

-

Treat any urinary tract infection, urethral strictures or obstructions.

-

Optimize general health (nutrition, smoking cessation, pelvic floor readiness).

-

Educate the patient about the device, risks, expected outcome and timing of surgery. Setting realistic expectations improves satisfaction.

Post-Implantation Management and Long-Term Care

-

Ensure the patient understands how to operate the device, signs of malfunction, and how to contact the urology team if problems arise.

-

Lifestyle modifications continue to matter: Avoid high-impact activities early; ensure smooth bowel habits; avoid heavy straining; maintain pelvic floor strength.

-

Monitor for signs of complications: increased leakage, pain, infection, pump malfunction, urethral erosion (see next section). Early recognition helps salvage device function.

-

Regular follow-up: Some surgeons recommend annual check-ups to assess device function (though exact schedules vary).

-

Patient should inform other healthcare providers of the presence of an AUS (important for catheterization, cystoscopy, MRI compatibility, surgical planning) - this can prevent inadvertent damage.

-

Planning for device longevity: The patient should be aware that while many AUS devices last a decade or more, revision is not uncommon; therefore the patient should maintain ongoing engagement with urology.

-

Psychological/social support: Addressing the patient's confidence, social reintegration, sexual function (especially in men) is important. Peer-support groups or continence associations may help.

In short: good peri-operative management, patient education and lifestyle support maximize the benefits of an AUS and minimise complications.

Complications of Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

No surgical intervention is entirely without risk; successful outcomes with AUS rely in part on careful anticipation and management of complications.

Common Complications

-

Mechanical failure: Device parts (cuff, tubing, pump, balloon) can malfunction. Long-term survival varies; some series report device survival at 5 years ~74%.

-

Urethral erosion: The cuff can erode into or through the urethra, especially in patients with prior radiation, urethral surgery or poor tissue quality.

-

Infection: Implant infections may require explantation of the device. Some series report explant rates ~17.6% in women.

-

Urethral atrophy: Over time, the pressure from the cuff may compress and thin the urethra, leading to recurrent incontinence or device failure.

-

Bladder outlet obstruction/urinary retention: If the cuff pressure is too high, or if bladder contraction is weak, the patient may have difficulty voiding.

-

Migration/malposition of cuff or pump: Leading to leakage or palpation/discomfort.

-

Complications in special populations (e.g., neurogenic bladder): Higher revision rates, more complex management.

Risk Factors for Complications

-

Prior pelvic radiation, which impairs tissue healing and blood supply.

-

History of prior incontinence surgery, urethral stricture repair or urethroplasty (so-called "fragile urethra"). For example, a study found that trans-corporal cuff placement in patients with a fragile urethra reduced revision/erosion rates compared with standard placement.

-

Low surgical volume / inexperienced surgeon. Devices implanted by low-volume surgeons have higher failure/revision rates.

-

Active infection, untreated bladder dysfunction, poor manual dexterity, poor general health.

Management of Complications

-

Infections/erosion often require device explantation and delay of re-implantation until tissue healing and infection control are complete.

-

Mechanical failure: Device revision or replacement may be planned; many series show revision rates of ~20-30% over several years.

-

Urethral atrophy or recurrent incontinence: Options include cuff downsizing, tandem cuffs, repositioning, adjustable pressure balloons.

-

Retention: May need cuff deactivation or adjustment.

-

Prevention strategies: Use of antibiotic-coated devices, careful surgical technique, choosing trans-corporal placement in fragile urethra cases, selecting experienced surgeon.

In summary: although AUS implantation offers very good continence outcomes, it is not a "once and forget" procedure-ongoing monitoring, awareness of complications and readiness to intervene are key to long-term success.

Living with the Condition of Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

How does life change for patients after they undergo implantation of an AUS? What should they know? What lifestyle issues matter?

Psychological and Social Aspects

-

Many patients experience dramatic improvement in their quality of life: fewer leaks, fewer pad changes, increased confidence, improved social and intimate life. For example, studies show >90% satisfaction in some cohorts.

-

Social reintegration: Being comfortable leaving the house, travelling, participating in physical exercise, returning to work or hobbies.

-

Intimate/sexual life: In men, improved continence often positively affects sexual activity and self-esteem. In women, careful counselling is needed about vaginal anatomy and device presence.

-

Emotional support: Patients may still have anxiety about device malfunction or leakage, so ongoing reassurance and counselling may help.

Practical Day-to-Day Tips

-

Learn to operate the pump (every patient should be trained by the surgical/continence team).

-

Maintain a smooth voiding schedule, avoid straining, manage bowel habits to avoid increased intra-abdominal pressure.

-

Be mindful of activities: For example, heavy lifting, cycling, horse-riding can put pressure on the cuff or pump - your doctor will advise when and how to resume these.

-

Travel: Many patients travel without issue, but carrying documentation about the device and awareness of potential concerns (airport security, MRI compatibility) is useful.

-

Medical procedures: Always inform other health-care providers (dentist, surgeon, urologist, radiologist) about the AUS - especially if catheterisation, cystoscopy or MRI is planned.

-

Device longevity: While many devices last a decade or more, revision may be necessary; keep in touch with your urology team and attend follow-up visits.

What to Do in Case of Problems

-

If you notice increased leakage, pain around the device, urinary retention, signs of infection (redness, fever, swelling) - contact your urologist promptly.

-

If you are unable to operate the pump or feel that voiding is impaired - ask for evaluation (which may include imaging or device assessment).

-

Keep pad usage diary - if leakage increases, it may signal device malfunction or change in bladder/urethral function.

Long-Term Expectations

-

Many patients enjoy continent or near-continent status (≤1 pad/day) for many years.

-

Device survival: While some devices may function well >10 years, studies indicate revision risk increases with time. For example, a 5-year device survival rate ~74%.

-

The need for caution: Although life with an AUS is much better than life with uncontrolled incontinence, patients should understand that ongoing monitoring and possibly revision surgery are part of the journey.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Artificial Sphincters for Urinary Incontinence

1. What is an Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS)?

An artificial urinary sphincter is a surgically implanted device designed to

treat severe urinary incontinence caused by a weakened or damaged

natural sphincter muscle.

The device consists of three parts:

-

Cuff - placed around the urethra to control urine flow.

-

Pump - implanted in the scrotum (for men) or labia (for women) to activate the device.

-

Reservoir - filled with fluid, usually placed under the abdominal wall.

When the cuff is inflated, it closes the urethra to prevent leakage; when deflated using the pump, it allows urination.

2. Who is a candidate for an Artificial Urinary Sphincter?

AUS is typically recommended for patients who:

-

Have moderate to severe urinary incontinence not responding to medications, pelvic floor exercises, or other non-surgical treatments.

-

Have stress urinary incontinence, often following prostate surgery in men or pelvic surgery in women.

-

Have sufficient dexterity to operate the pump.

A detailed medical evaluation, including urinary tests and imaging, is required to confirm candidacy.

3. How is Artificial Sphincter Surgery performed?

The procedure is done under general or spinal anesthesia and usually lasts 1-2 hours.

Surgical steps include:

-

Making small incisions to place the cuff around the urethra.

-

Placing the pump in the scrotum or labia.

-

Inserting the fluid reservoir under the abdominal wall.

-

Connecting all components and testing the device.

Most patients stay in the hospital 1-2 days and receive detailed instructions on using the pump.

4. How effective is the Artificial Urinary Sphincter?

Studies show that 75-90% of patients achieve significant or complete

continence with an AUS.

While some minor leakage may occur, most patients can regain confidence in daily

activities and improve their quality of life dramatically.

5. What is the recovery time after AUS surgery?

-

Hospital Stay: 1-2 days.

-

Initial Recovery: Avoid strenuous activity for 4-6 weeks.

-

Pump Activation: Usually performed 4-6 weeks post-surgery, once healing is complete.

-

Full Recovery: Most patients resume normal activities within 6-8 weeks.

Patients are instructed on proper hygiene and handling of the device to prevent infection and ensure long-term functionality.

6. Are there any risks or complications?

As with any surgery, there are potential risks, including:

-

Infection (may require device removal in severe cases)

-

Mechanical failure of the device

-

Urethral erosion or atrophy

-

Pain or discomfort at the implant site

-

Difficulty using the pump in rare cases

Careful surgical technique, regular follow-ups, and proper patient education minimize these risks.

7. How long does an Artificial Sphincter last?

Modern AUS devices are designed to last 10-15 years on average. Device longevity depends on:

-

Frequency of use

-

Patient activity and lifestyle

-

Regular maintenance and follow-up care

Replacement or revision surgery may be necessary if mechanical failure or complications occur.

8. Can both men and women use an Artificial Urinary Sphincter?

Yes. While AUS devices were originally developed for men, modified devices and

surgical techniques allow women with severe stress incontinence to benefit

as well.

The procedure may differ slightly in terms of cuff placement and pump

location.

9. How do I use the Artificial Sphincter?

Using the AUS is straightforward:

-

To urinate: Squeeze the pump in the scrotum/labia to temporarily deflate the cuff.

-

After urination: The cuff automatically reinflates over a few minutes, closing the urethra.

Patients receive hands-on training and written instructions from their surgeon before discharge.

10. Is Artificial Urinary Sphincter surgery covered by insurance?

Yes. Most major insurance providers and government health

programs cover AUS implantation when medically necessary.

Coverage typically includes:

-

Surgeon fees

-

Hospital costs

-

Device cost

Patients should confirm specifics with their insurance provider and hospital billing department to avoid unexpected expenses.