Introduction to Coarctation of the Aorta

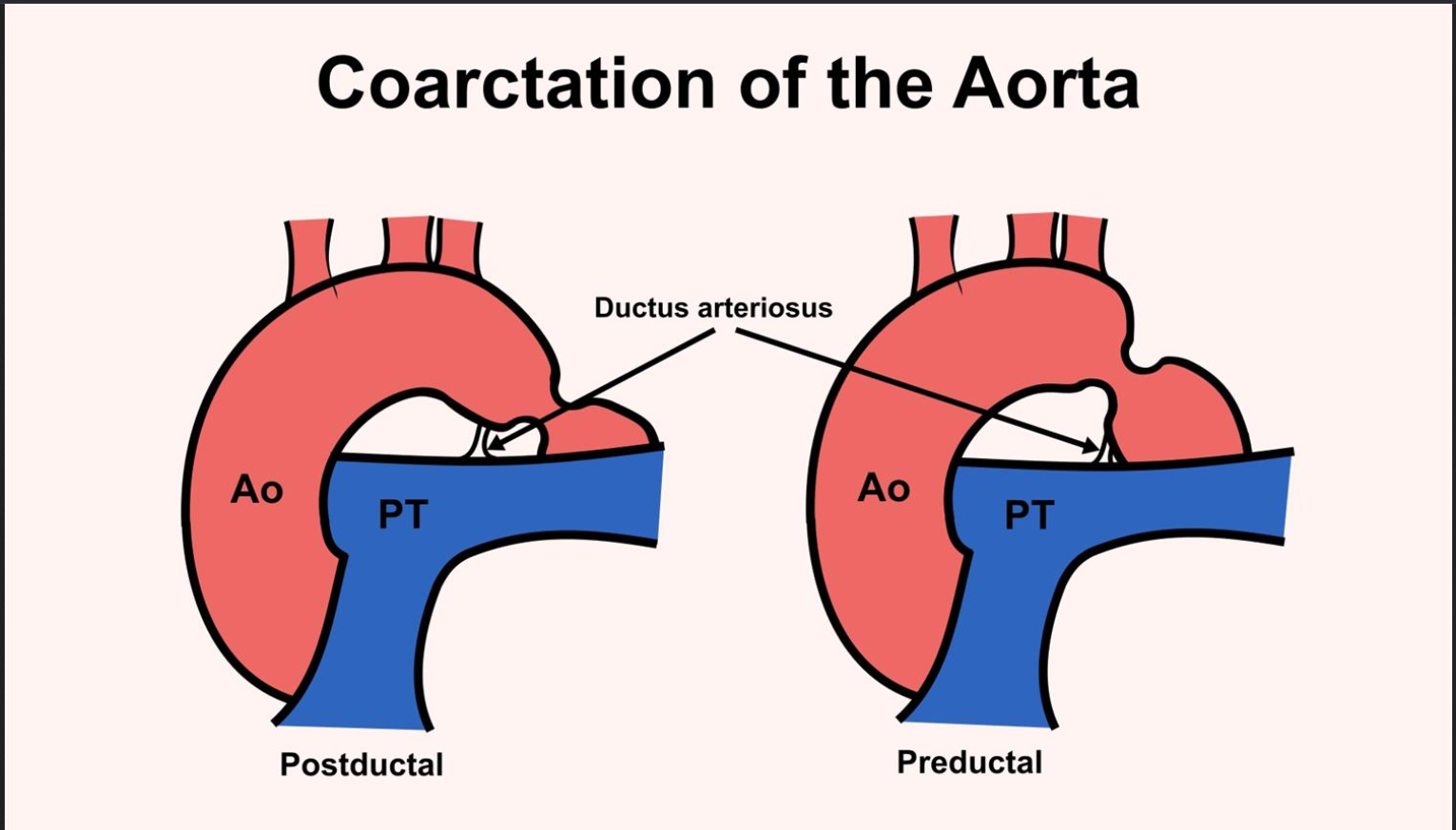

Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect in which a segment of the aorta-the main artery carrying oxygenated blood from the heart to the body-is narrowed or constricted. This narrowing obstructs normal blood flow, forcing the heart to work harder to push blood through the narrowed section. As a result, blood pressure rises in the upper body and decreases in the lower body, causing a significant imbalance in circulation.

This condition typically occurs just beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery, near the site where the ductus arteriosus (a fetal blood vessel) attaches to the aorta. Depending on the location and extent of the narrowing, the condition may range from mild to severe. In severe cases, especially in newborns, it can cause life-threatening heart failure if not promptly treated.

Coarctation of the Aorta accounts for about 5-8% of all congenital heart diseases. It affects both genders but is slightly more common in males. Many patients also have associated heart defects, particularly a bicuspid aortic valve (present in up to 75% of cases), which can complicate the clinical picture.

Understanding this condition is vital because, if untreated, CoA can lead to persistent hypertension, heart failure, aortic aneurysm, or stroke. Fortunately, with modern diagnostic tools and surgical or interventional treatments, most patients can achieve excellent long-term outcomes and live full, active lives.

Causes and Risk Factors of Coarctation of the Aorta

The primary cause of coarctation of the aorta is abnormal development of the aortic arch before birth, making it a congenital heart defect. Most cases are diagnosed in infancy or childhood, but rarely, it can develop later in life due to trauma, atherosclerosis, or inflammatory conditions like Takayasu arteritis. The precise reason for the congenital form remains unknown, but both genetic and environmental factors during pregnancy are implicated.

Common causes / underlying mechanisms

-

CoA is fundamentally a congenital anomaly of the aortic arch/descending aorta whereby there is narrowing (stenosis) or hypoplasia of a segment of the aorta.

-

Embryologically, errors in aortic arch development (e.g., abnormal migration or differentiation of neural-crest derived cells, abnormal remodeling of the aortic arch) are implicated in many cases of isolated CoA.

-

Histologically, the region of coarctation may include ductal tissue or abnormal vessel wall architecture that predisposes to narrowing over time.

-

CoA may also occur in the setting of other congenital heart defects (e.g., bicuspid aortic valve, ventricular septal defect, left heart obstructive lesions) so the narrowing may be part of a complex cardiac anatomy rather than isolated.

Risk factors

-

Genetic syndromes: For instance, females with Turner Syndrome (45,X or variants) have a higher propensity for coarctation.

-

Family history: There is familial clustering in some cases, suggesting a heritable component even in “isolated” CoA.

-

Maternal and prenatal factors: Some studies suggest that prenatal factors such as altered hemodynamics, maternal diabetes, or other environmental exposures may slightly increase risk though clear causation is less well-defined in CoA than in some other congenital defects.

-

Associated vascular wall pathology: Some patients have a broader arteriopathy (vessel wall abnormality) that may predispose to coarctation plus aneurysm formation later.

Why the risk matters

Understanding causes and risk factors helps clinicians identify candidates for screening (for example siblings, or children of mothers with known risk) and ensures that once diagnosed, management considers associated networks (other heart defects, vascular abnormalities, genetic syndromes). Early recognition leads to better outcomes.

Symptoms and Signs of Coarctation of the Aorta

This section covers how CoA manifests-both in infancy/childhood and later life-and what clinical examination may reveal.

Symptoms by age of presentation

Infants / neonates (severe obstruction):

-

May present early with heart failure, poor feeding, respiratory distress, lower body perfusion compromise shortly after ductus arteriosus closes.

-

Signs of shock, acidosis, weak or absent femoral pulses, differential blood pressure between upper and lower limbs.

Children / adolescents (moderate narrowing):

-

Hypertension (upper limbs), headaches, nosebleeds (epistaxis) due to increased upper body pressure.

-

Leg fatigue, claudication or cold lower limbs during exercise due to reduced distal flow.

-

Collateral circulation signs (rib-notching on x-ray, more visible intercostal vessels) may develop.

Adults (undetected or residual CoA):

-

Persistent or newly diagnosed hypertension despite treatment.

-

Aortic aneurysm/dissection risk elevated.

-

Heart failure signs, premature coronary disease, stroke risk increased.

Signs on physical examination

-

Difference in blood pressure (and pulses) between upper and lower limbs: often high in arms, low in legs. Delayed up-stroke in femoral pulses (“brachial-femoral delay”).

-

Systolic murmur (often heard on the back between the scapulae) due to turbulent flow across the narrowed segment or collateral vessels.

-

Rib-notching on chest x-ray (due to enlarged intercostal arteries forming collateral flow) in older children/adults.

-

Left ventricular hypertrophy signs (on ECG/echo) because of increased afterload.

Why recognising symptoms/signs matters

Early detection based on these clues allows timely imaging, diagnosis and intervention before major complications such as hypertensive damage, aortic rupture or heart failure occur. It also emphasises the importance of measuring blood pressure in both arms and legs in suspected cases.

Diagnosis of Coarctation of the Aorta

Here we discuss how the condition is diagnosed and evaluated-including imaging, hemodynamics and associated investigations.

Initial work-up and screening

-

Measurement of blood pressure in both arms and legs. Persistent difference or gradient triggers further investigation.

-

Pulse examination: delayed or diminished femoral pulses relative to radial/brachial pulses.

-

ECG and chest-X-ray may provide clues (LVH, rib-notching, “figure-3 sign” on aorta contour) though not definitive.

Imaging & advanced diagnostics

-

Echocardiography (transthoracic or trans-oesophageal): first-line in children and infants to visualise the aortic arch, measure gradients, assess LV function and associated cardiac anomalies (eg bicuspid aortic valve).

-

CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA): Provide detailed 3-D anatomy of the aortic arch, descending aorta, collateral vessels, aneurysms, hypoplastic segments. Key for planning intervention, especially in older children, adolescents and adults.

-

Cardiac catheterisation / angiography: May be used when non-invasive imaging is inconclusive or when planning interventional therapy (to measure precise gradients, anatomy, collaterals).

Associated investigations

-

Evaluation for associated heart abnormalities (e.g., bicuspid aortic valve, ventricular septal defect).

-

Assessment of hypertensive damage: renal function, cerebrovascular assessment if hypertension present.

-

Long-term follow-up imaging to detect recoarctation or aneurysm formation.

Why diagnosis and evaluation are critical

Accurate diagnosis identifies the location and severity of narrowing, presence of collaterals, associated defects and guides the timing and type of intervention. Proper evaluation reduces risk of residual disease, complications and improves life expectancy.

Treatment Options of Coarctation of the Aorta

This is the core section: it outlines how CoA is treated - including surgical, percutaneous and medical adjuncts.

Timing of treatment

Treatment often depends on age at diagnosis, severity of obstruction, presence of symptoms, hypertension, and associated anomalies. Many recommend early repair (infancy) for significant narrowing; in older children/adults, intervention is still beneficial though outcomes may carry increased background risk due to long-standing hypertension.

Surgical treatment options

-

Resection with end-to-end anastomosis: removal of narrowed segment and direct connection of the two ends of the aorta. Historically common.

-

Extended end-to-end anastomosis: includes a larger portion of aorta (arch plus isthmus) to address hypoplastic arch in addition to coarctation. Shown to reduce re-coarctation.

-

Subclavian flap aortoplasty: uses a flap of left subclavian artery to enlarge constricted aortic segment. Less commonly used in some centres.

-

Patch aortoplasty: opening the narrowed area and inserting a patch to widen it (occasionally associated with aneurysm risk).

Percutaneous / catheter-based interventions

-

Balloon angioplasty: dilatation of the narrowed segment via catheter in older children/adults or as interim therapy. However risk of aneurysm or re-narrowing may be higher.

-

Stent placement: implanting a stent in the narrowed aorta to hold it open, widely used in older children and adults. Particularly useful for recoarctation or residual narrowing after surgery.

Medical and adjunctive therapy

-

Management of hypertension (medical therapy: ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, etc.) even after repair, because many patients remain hypertensive long-term.

-

Lifelong surveillance: imaging for aneurysm, recoarctation, vascular complications.

-

Optimization of other cardiovascular risk factors (lipids, diabetes, lifestyle) given elevated risk of atherosclerosis in some patients.

Outcomes and expectations

-

When treated early and appropriately, survival and quality of life are significantly improved. Many patients go on to normal daily activities.

-

Even after repair, risk of hypertension, recoarctation, aneurysm remains, hence follow-up is essential.

Choosing between options

The choice (surgery vs stent vs balloon) depends on factors such as age, anatomy (length of narrowing, arch hypoplasia), presence of other cardiac defects, collateral circulation, and institutional expertise. Multi-disciplinary decision-making is key.

Prevention and Management of Coarctation of the Aorta

Although congenital, some aspects of management and secondary prevention are important.

Prevention (primary)

-

Since CoA is congenital and often arises during fetal development, primary prevention is limited. However, careful prenatal care, monitoring of mothers at risk (e.g., with known congenital heart disease) may help early detection.

-

Genetic counselling for families with history of congenital heart defects may assist risk stratification.

Management (secondary)

-

Post-repair, strict blood pressure control is mandatory because persistent hypertension is common.

-

Lifestyle modifications: healthy diet, regular physical activity, non-smoking, weight management - these reduce cardiovascular risk which is elevated in CoA patients.

-

Regular imaging / surveillance to detect: recoarctation, aneurysm formation at repair site or elsewhere in the aorta, premature atherosclerosis.

-

Coordination of care across lifespan: from childhood into adulthood, transition of congenital heart disease (CHD) patients to adult cardiology is vital.

-

Pregnancy management: Women with repaired CoA should have pre-conception counselling and careful monitoring during pregnancy (risk of hypertension, aortic dilation).

Why prevention/management matters

Management ensures that even after successful repair, long-term outcomes remain good. Without vigilance, late complications can undercut the benefit of early treatment.

Complications of Coarctation of the Aorta

Both untreated and treated CoA have risks; understanding complications helps in counselling and monitoring.

Untreated or delayed treatment complications

-

Severe hypertension leading to target organ damage (heart, kidneys, brain).

-

Left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure or dysfunction.

-

Aortic aneurysm and dissection proximal or distal to the coarctation site.

-

Cerebral aneurysm and intracranial haemorrhage due to elevated proximal pressure.

-

Lower limb ischemia, exercise intolerance, claudication.

Post-treatment complications

-

Recoarctation: re-narrowing of the aorta after repair, which may require re-intervention.

-

Aneurysm formation: especially at repair sites or patch/ graft sites in adulthood; predisposed to rupture or dissection.

-

Persistent hypertension: despite the relief of narrowing, many individuals continue to have elevated blood pressure.

-

Arterial stiffening and early atherosclerosis: Evidence shows patients post-CoA repair may have accelerated vascular aging and higher risk of cardiovascular events.

-

Other cardiovascular complications: such as coronary disease, aortic valve disease (e.g., bicuspid aortic valve), heart failure.

Monitoring and addressing complications

Being aware of these potential complications underscores the need for lifelong follow-up, surveillance imaging, blood pressure monitoring, and multidisciplinary care. Early intervention improves outcomes.

Living with the Condition of Coarctation of the Aorta

This section deals with life before diagnosis/repair (when relevant) and life after treatment - realistic expectations, lifestyle, and long-term outlook.

Before treatment

-

In cases where CoA is diagnosed late, individuals may have endured hypertension or vascular changes for years. This may mean they have early organ damage (kidney, heart, brain) at the time of intervention.

-

Psychosocial impact: Children or adults with untreated CoA may struggle with exercise intolerance, leg fatigue, or restrictions in physical activity, which can affect quality of life.

-

Important to educate patients/families about the nature of the disease, the need for treatment, and the long-term implications.

After treatment - recovery and life-long health

-

Post-repair, many patients resume normal daily activities, including exercise and work. With proper treatment, the outlook is very good.

-

However, patients must be aware of the need for lifelong surveillance - even in the absence of symptoms. This includes periodic imaging, blood pressure checks, lifestyle management and follow-up with congenital heart disease specialists.

-

Some limitations may persist: e.g., reduced exercise capacity compared to peers, need for ongoing blood pressure medications, or monitoring for late vascular changes.

Lifestyle and self-care

-

Strict blood pressure control is paramount. Home monitoring may be useful.

-

Adopt cardiovascular-healthy habits: non-smoking, regular aerobic and strength exercises, balanced diet, stress management.

-

Inform all healthcare providers of history of CoA repair (especially when prescribing medications or in case of pregnancy).

-

Work, sports and activities: Many patients can engage fully, but competitive athletics should be assessed individually by cardiologist/CHD specialist.

-

Transition from pediatric to adult congenital cardiology care is important - many patients “fall off” after childhood; continuity of care matters.

Special considerations in India / low-resource settings

-

Diagnosis may be delayed or missed; raising awareness among primary-care, paediatricians of upper-vs-lower limb blood pressure difference can help.

-

Access to specialized congenital cardiac centres for repair and long-term follow-up may be limited - thus emphasising the need for coordination and referral networks.

-

Cost, follow-up logistics and patient education may be more challenging; local adaptations (community follow-up, linking with adult CHD networks) may help.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Coarctation of the Aorta

1. What Is Coarctation of the Aorta?

Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect where a section of the aorta - the main artery carrying oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the body - is narrowed or constricted.

This narrowing forces the heart to pump harder to move blood through the aorta, leading to high blood pressure (hypertension) in the upper body and poor circulation in the lower body.

CoA can range from mild to severe, and in serious cases, it can cause heart failure, stroke, or organ damage if left untreated.

The condition can occur alone or along with other congenital heart defects, such as a bicuspid aortic valve or ventricular septal defect (VSD).

2. What Causes Coarctation of the Aorta?

The exact cause of CoA isn’t fully understood, but it typically develops before birth as part of abnormal heart or vessel formation during fetal development.

Possible contributing factors include:

-

Genetic abnormalities (e.g., Turner syndrome)

-

Family history of congenital heart defects

-

Developmental issues during fetal growth of the aorta

In some cases, coarctation can appear after birth due to inflammation or trauma, but this is rare.

3. What Are the Common Symptoms of Coarctation of the Aorta?

Symptoms depend on the severity and age of the patient.

In Infants (Severe CoA):

-

Pale or bluish skin

-

Difficulty breathing

-

Poor feeding and weight gain

-

Excessive sweating

-

Signs of heart failure

In Older Children and Adults (Mild to Moderate CoA):

-

High blood pressure (especially in the arms)

-

Headaches or nosebleeds

-

Cold legs or feet

-

Muscle weakness or cramping in the lower body

-

Chest pain or shortness of breath during exercise

Sometimes, CoA may go unnoticed until adolescence or adulthood, discovered during a routine blood pressure check showing differences between arms and legs.

4. How Is Coarctation of the Aorta Diagnosed?

Diagnosis begins with a physical examination and blood pressure

measurement in both the arms and legs.

Doctors often notice higher blood pressure in the upper body and

weaker pulses in the legs.

Diagnostic tests include:

-

Echocardiogram (Echo): The primary test that uses sound waves to visualize the heart and aorta.

-

Chest X-ray: May show an enlarged heart or “3 sign” indicating aortic narrowing.

-

CT Angiography or MRI: Provides detailed images of the aorta and surrounding vessels.

-

Cardiac Catheterization: Measures pressure differences across the narrowed area and sometimes used to treat the narrowing.

Early diagnosis is crucial to prevent complications like hypertension and heart failure.

5. How Is Coarctation of the Aorta Treated?

Treatment depends on the patient’s age, the severity of the narrowing, and whether other

heart defects are present.

The main goal is to restore normal blood flow through the aorta and

reduce strain on the heart.

Treatment Options:

-

Surgical Repair:

-

The narrowed section of the aorta is removed and the healthy ends are reconnected (end-to-end anastomosis).

-

In some cases, a synthetic patch or graft is used to widen the area.

-

-

Balloon Angioplasty and Stent Placement:

-

A catheter with a small balloon is inserted into the narrowed area and inflated to open it.

-

A stent (metal mesh tube) may be placed to keep the artery open.

-

This is often used in older children and adults or when narrowing returns after surgery.

-

-

Medication:

-

Drugs to control blood pressure or manage heart failure symptoms before or after surgery.

-

6. What Is the Difference Between Surgery and Balloon Angioplasty?

Surgical repair is often recommended for infants and young children, as it provides a long-term solution and can address associated heart defects during the same operation.

Balloon angioplasty, on the other hand, is less invasive and often used for:

-

Older children or adults

-

Re-narrowing after previous surgery (re-coarctation)

While angioplasty involves shorter recovery time, surgery remains the preferred approach for complex or severe cases.

7. What Is the Recovery Process After Treatment?

Recovery varies depending on whether the patient had open surgery or catheter-based treatment.

After Surgery:

-

Hospital stay: 5-10 days for monitoring heart function and blood pressure.

-

Temporary fatigue, soreness, and mild pain near the incision site.

-

Follow-up visits to check blood pressure and healing.

After Balloon Angioplasty:

-

Hospital stay: Usually 1-2 days.

-

Light activity resumed in 1 week; full recovery within 2-3 weeks.

In both cases, patients must have regular cardiac follow-ups to ensure the repaired area remains open and to monitor for re-narrowing or high blood pressure.

8. Are There Any Risks or Complications Associated With the Condition or Treatment?

Untreated Coarctation of the Aorta can lead to serious complications, including:

-

Chronic high blood pressure

-

Aortic aneurysm or rupture

-

Heart failure

-

Stroke or brain hemorrhage

-

Early coronary artery disease

After treatment, potential complications may include:

-

Re-narrowing (re-coarctation)

-

Aortic aneurysm at the repair site

-

Persistent hypertension

These risks are minimized with early diagnosis, proper treatment, and lifelong cardiac monitoring.

9. Can Coarctation of the Aorta Recur After Treatment?

Yes, in some cases, re-narrowing (re-coarctation) can occur months or years after the initial repair, especially in:

-

Infants operated on at a very young age

-

Patients with associated heart defects

If narrowing recurs, it can often be treated successfully with balloon angioplasty or a stent placement.

Regular follow-up with a pediatric or adult congenital cardiologist is essential to detect and manage such complications early.

10. What Is the Long-Term Outlook for Patients With Coarctation of the Aorta?

With timely treatment and proper follow-up, most patients with CoA enjoy normal, healthy, and active lives.

Long-term expectations include:

-

Normal heart function after successful repair

-

Lifelong monitoring for blood pressure control

-

Regular echocardiograms or MRIs to ensure the aorta remains open

-

Possible medications to manage hypertension

Women with repaired CoA can usually have healthy pregnancies, but they should be closely monitored by a cardiologist and obstetrician experienced in congenital heart conditions.

Early treatment and ongoing care are key to preventing complications and ensuring a healthy life expectancy.