Introduction to Craniotomy

A craniotomy is a major neurosurgical procedure in which a portion of the skull (the "bone flap") is temporarily removed in order to access the brain. The objective is to treat or relieve an intracranial condition-such as a tumour, haemorrhage, vascular malformation, traumatic brain injury, or an infection-by providing surgeons access to the brain tissue beneath the skull. Once the underlying procedure is completed, the bone flap is typically replaced and fixed in position using plates and screws, and the incision is closed. In modern practice, craniotomies vary in size and approach-from large traditional openings to more minimally-invasive "keyhole" or "mini" craniotomies. The choice of approach depends on the lesion's location, size, the patient's condition, and the neurosurgeon's plan.

Beyond just "opening the skull," the procedure involves careful pre-operative planning (using imaging modalities such as CT and MRI), intra-operative navigation (sometimes using stereotactic or image-guided tools), and post-operative care, including monitoring for complications, managing pain, and supporting rehabilitation. For patients and families, understanding what craniotomy involves-why it is done, what to expect before, during and after the surgery-can help reduce anxiety and improve preparedness.

Causes and Risk of Craniotomy

Craniotomy is a surgical procedure where part of the skull is temporarily removed to access the brain. It is performed for a variety of urgent and planned reasons, but the procedure has significant risks due to the complexity of brain surgery and the critical functions in the area being operated on.

Why a craniotomy may be required

There are many intracranial conditions for which a craniotomy may become necessary. These include:

-

Brain tumours (primary or metastatic) that require removal or biopsy to relieve mass effect, reduce intracranial pressure or improve neurologic function.

-

Intracranial haemorrhage (such as subdural haematoma, epidural haematoma, intracerebral bleed) where removal of the clot or bleeding source is required and access must be granted.

-

Cerebral aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) where a surgeon may need to clip an aneurysm or remove/repair a vascular malformation.

-

Traumatic brain injury with depressed skull fractures, foreign bodies, brain swelling or bleeding requiring surgical intervention.

-

Brain infections or abscesses that need surgical drainage or debridement through direct access to the brain.

-

Hydrocephalus or obstructive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) disorders in selected cases where access is needed to relieve pressure or install bypass shunts.

Risks that increase need or complicate a craniotomy

While the procedure itself is a response to a condition, there are patient-related and lesion-related risk factors that may increase both the need for craniotomy and the risk of poor outcome. These include:

-

Advanced age or frailty, which may reduce the ability to tolerate surgery and recover.

-

Existing comorbidities (heart disease, lung disease, uncontrolled diabetes, coagulation disorders) that increase surgical risk.

-

Large or deep-seated lesions in difficult to access brain regions, which make surgery more complex.

-

Brain swelling or elevated intracranial pressure pre-operatively, which complicates both the procedure and recovery.

-

Prior brain surgery or radiation, which may lead to scar tissue, altered anatomy and increased bleeding risk.

-

Pre-existing neurological deficits, which may limit recovery potential.

In summary, the decision to perform a craniotomy balances the serious underlying condition that requires treatment against the risks of surgery. The neurosurgical team assesses the patient's overall health, imaging findings, surgical approach options, and the expected benefits and risks before recommending the procedure.

Symptoms and Signs of Conditions Requiring Craniotomy

Because craniotomy is a means to an end (i.e., treating an underlying brain condition), the symptoms and signs vary according to the condition being treated-but there are shared warning features of serious intracranial disease. Recognising these helps in earlier diagnosis and referral.

Common symptoms

-

New or worsening headaches: especially those that are persistent, progressive, or different in character (e.g., worse on lying down, worse on waking, with vomiting).

-

Neurological changes: weakness in one side of the body (hemiparesis), numbness or tingling, difficulty speaking or understanding language, sudden visual loss or changes, seizures.

-

Sudden loss of consciousness, confusion or drowsiness: may indicate bleeding, swelling or raised intracranial pressure.

-

Changes in behaviour or cognitive function: memory problems, personality changes, difficulty concentrating, increased irritability.

-

Signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP): nausea/vomiting, blurry vision, papilledema (on examination), altered mental state, unequal pupils.

-

Focal neurological signs: depending on the lesion's location, symptoms like hearing loss (if tumour in cerebellopontine angle), ataxia (if cerebellar), cranial nerve palsies.

Physical and examination findings

-

On neurological exam: decreased strength, abnormal reflexes, abnormal coordination, decreased level of consciousness.

-

Scalp swelling or a skull fracture in trauma cases.

-

Evidence of increased intracranial pressure: for example papilloedema on fundus examination, bradycardia/hypertension/irregular breathing (Cushing's triad) in severe cases.

-

Imaging hints (though not symptoms): midline shift, mass effect on imaging, hydrocephalus.

Early identification of these signs and timely investigations are critical so that the neurosurgical team can plan and intervene before permanent damage occurs.

Diagnosis of Conditions Requiring Craniotomy

Diagnosis is a multi-step process combining patient history, physical/neuro examination, imaging, and sometimes invasive monitoring or special tests-all to define the nature of the intracranial problem and plan the surgery.

History and examination

The patient interview explores onset, duration and progression of symptoms (headache, seizures, focal deficits, trauma). The neurological exam assesses level of consciousness (for example via Glasgow Coma Scale), motor and sensory function, cranial nerves, cerebellar/coordination testing, signs of raised intracranial pressure, and overall medical status (comorbidities, medications, especially anticoagulants).

Imaging studies

-

CT scan (non-contrast and with contrast) is often first-line, especially in acute settings (trauma, haemorrhage) to rapidly identify bleeding, fractures, mass effect or hydrocephalus.

-

MRI/MRA provides more detailed views of brain tissue, vascular structures, tumours, and is useful for surgical planning, especially for lesions in tricky locations.

-

CT or MR angiography when vascular lesions (aneurysms/AVMs) are suspected.

-

Functional MRI, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), tractography in selected cases for mapping critical brain pathways pre-operatively.

-

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) in complex vascular cases.

Additional tests and monitoring

-

Blood tests (including coagulation, complete blood count, electrolytes, renal/liver profile) to assess surgical risk.

-

Possibly intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with high suspicion of raised ICP and when surgical timing is being evaluated.

-

Neurophysiological monitoring or intra-operative mapping may be planned, especially if the lesion is in or near eloquent brain regions (speech, motor cortex).

-

Pre-operative anaesthetic assessment including cardiac and pulmonary evaluation.

Surgical planning

Using the data above, the neurosurgeon identifies the optimal approach (which skull region, size of bone flap, what instruments/navigation to employ), estimates risks, discusses with anaesthesia, critical care, and rehabilitation teams, and plans for both the operation and post-operative care.

Treatment Options of Craniotomy

The term "treatment options" in the context of craniotomy actually refers to both the decision-making around performing the craniotomy and the intra-operative and post-operative management strategies.

Indications and decision-making

Craniotomy is indicated when the benefits of gaining access to the brain (for tumour removal/biopsy, clot evacuation, vascular repair, infection drainage) outweigh surgical risks. The neurosurgical team must evaluate: patient's general health and fitness for surgery, the expected functional outcome, alternatives (for example non-surgical options, less invasive endovascular techniques for vascular lesions), and timing (urgent vs elective).

Surgical approaches

-

Traditional open craniotomies: large skull openings when the pathology is large, deep or complex and requires wide exposure.

-

Minimally invasive or "keyhole" craniotomies: smaller openings, less disruption of tissue, shorter recovery, used for select lesions in favourable locations.

-

Endoscopic or microscopic assisted craniotomies: using cameras or microscopes to reduce brain manipulation, improve precision.

-

Navigation-guided or stereotactic craniotomies: use of real-time imaging, frameless systems, intra-operative MRI/CT to guide the surgeon to the target with minimal collateral damage.

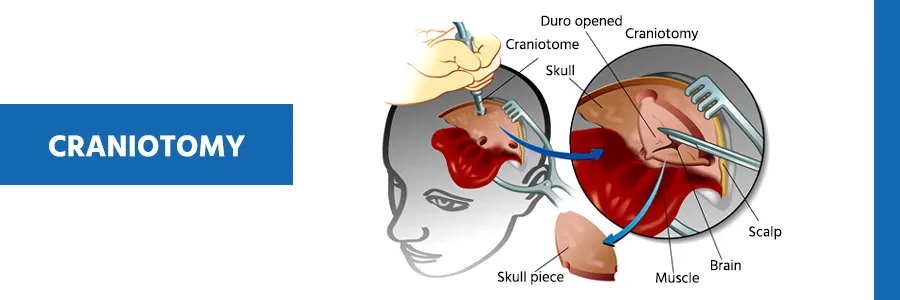

Within the operation, after removal of the skull flap, the surgeon opens the dura mater, manipulates the brain as required, deals with the pathology (tumour removal, clipping of aneurysm, evacuation of haematoma, drainage of abscess), achieves haemostasis, closes the dura, reattaches the bone flap (fixing with plates/screws) and closes the scalp.

Post-operative management

Following surgery the patient is transferred to intensive care or high-dependency neurosurgical ward. Key aspects of post-operative management include:

-

Monitoring level of consciousness and neurological status.

-

Monitoring intracranial pressure (if applicable).

-

Pain management and control of nausea/vomiting.

-

Prevention of complications: infection (prophylactic antibiotics, wound care), deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary complications.

-

Early mobilisation and initiation of rehabilitation (physical/occupational/speech therapy) as soon as safe.

-

Imaging follow-up (CT/MRI) to assess for residual lesion, edema, bleeding, or complications.

-

Coordination between neuro-surgery, ICU, rehabilitation and nursing teams to optimise recovery.

Alternatives or adjuncts

In some cases, alternatives to craniotomy may include endovascular treatments (for aneurysms/AVMs), radiosurgery (for selected small tumours), medical management of intracranial pressure, or conservative monitoring. The neurosurgical team may also plan adjuncts such as intra-operative neurophysiological monitoring, awake craniotomy (in select cases of brain tumour in eloquent areas), and pre-habilitation (optimising patient condition pre-operatively).

Prevention and Management of Craniotomy

Prevention and management of complications after craniotomy are critical for optimizing neurological outcomes, functional recovery, and quality of life. This involves surgical strategies to reduce risk, vigilant perioperative care, and structured multidisciplinary rehabilitation for all patients.

Prevention of complications and optimisation of outcome

Prevention in the context of craniotomy mainly refers to minimising surgical risk and optimising patient status to improve outcomes. Key points include:

-

Careful pre-operative assessment of patient fitness for surgery: controlling blood pressure, diabetes, heart/lung disease, stopping or managing anticoagulants/antiplatelets appropriately.

-

Pre-operative imaging and planning to make the procedure as precise and minimally traumatic as possible.

-

Use of minimally invasive techniques when feasible to reduce operative trauma, blood loss and recovery time.

-

Intra-operative protective measures: accurate navigation, microsurgical technique, careful handling of brain tissue, minimizing retraction and exposure time.

-

Post-operative vigilance: strict aseptic technique, wound care, early detection of complications (e.g., CSF leak, infection, bleeding), and early mobilisation to reduce risks of complications like pneumonia, DVT.

Management after craniotomy

Once the surgery is completed, the ongoing management is crucial to ensure healing, recovery of neurological function, and quality of life. This involves:

-

Neuro-rehabilitation: physical therapy to regain strength, mobility and coordination; occupational therapy to restore independence in daily activities; speech/language therapy if there are deficits.

-

Cognitive rehabilitation: many patients may have memory, attention, executive function issues-assessment and targeted therapy help.

-

Monitoring for and managing complications: such as seizures (antiepileptic medications where indicated), hydrocephalus (may require shunting), skull healing problems (bone flap resorption, infection), wound healing issues.

-

Lifestyle modification and preventive care: depending on the underlying condition, e.g., tumour follow-up, vascular risk factor control (hypertension, smoking cessation, cholesterol), head injury prevention (helmet use, falls prevention).

-

Follow-up imaging and consultations: to assess for residual lesions, recurrence, or new pathology; also to ensure skull flap is intact and healing well.

-

Psychosocial support: dealing with the emotional impact of brain surgery, possible changes in cognitive/physical function, supporting family/caregiver involvement, addressing quality of life issues.

Complications of Craniotomy

While craniotomy is a life-saving or life-improving surgery in many cases, like all major procedures it carries risks. Some of the common and serious complications include:

-

Infection: wound infection, meningitis, brain abscess.

-

Bleeding or haematoma formation: either intra-operatively or post-operatively, which may necessitate further surgery.

-

Seizures: the brain manipulation and underlying lesion increase seizure risk; may require long-term antiepileptic therapy.

-

Neurological deficits: despite successful surgery, a patient may be left with weakness, speech problems, sensory deficits, visual changes or cognitive impairment, especially if the underlying condition or surgery was near eloquent brain areas.

-

CSF leak or hydrocephalus: fluid leakage from the dura or malfunction of CSF pathways may require further intervention (e.g., shunt).

-

Bone flap complications: bone flap resorption, infection of plates/screws, deformity of skull.

-

Cerebral oedema/raised intracranial pressure: can occur post-operatively, particularly if the brain has already been injured or swollen.

-

General surgical risks: deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, heart or lung complications, anaesthetic risks.

Because of the significant risk profile, the neurosurgical team takes a multidisciplinary approach-surgeon, neuro-intensive care, neuro-rehabilitation, nursing-to minimise risk and manage complications quickly if they arise.

Living with the Condition After Craniotomy

Living with the aftermath of a craniotomy depends greatly on the underlying reason for the surgery, the patient's pre-operative condition, and how the recovery proceeded. Some key considerations include:

Physical recovery and mobility

Many patients will experience a gradual improvement in strength, coordination and stamina over weeks to months. Early rehabilitation is critical. There may be limitations-balance issues, weakness, fatigue, headaches, or altered sensation. Patients must pace themselves and avoid strenuous activity until cleared.

Cognitive and psychological recovery

Brain surgery and the underlying pathology often affect memory, attention, processing speed, executive functions and mood. It is common for patients to have some "brain fog", changes in personality or emotional lability. Cognitive rehabilitation and psychological support (for anxiety, depression) are often needed.

Return to everyday life

Patients may need to make modifications: avoiding contact sports or activities with high risk of head injury, using protective headgear if advised, regular check-ups with neurosurgery/neurology, monitoring for seizures and knowing when to seek medical attention. Lifestyle changes-such as controlling blood pressure, managing cholesterol, quitting smoking, maintaining healthy weight-support long-term brain health.

Long-term monitoring

Depending on the underlying lesion (tumour, vascular malformation, trauma), long term follow-up imaging may be needed. There may be a need for additional procedures, like a second surgery, cranioplasty (skull reconstruction), shunt placement, or further rehabilitation. Patients and caregivers should be aware of warning signs: new headache, seizures, neurological changes, infection signs at the surgical site.

Quality of life and support

Recovery from brain surgery is not just physical-it affects relationships, employment, independence, and mental health. Involving family/caregivers, connecting with support groups, rehabilitation teams and adapting expectations are important. Some patients may return to full function; others may need permanent accommodations (assistive devices, part-time or modified work). It is vital to set realistic goals and celebrate incremental improvements.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Craniotomy

1. What Is a Craniotomy?

A craniotomy is a surgical procedure in which a portion of the skull is temporarily removed to access the brain for treatment of various conditions.

After the surgery, the bone flap is typically replaced and secured using plates and

screws.

Craniotomy is performed to:

-

Remove brain tumors or cysts

-

Treat brain aneurysms or vascular malformations

-

Relieve pressure from traumatic brain injury

-

Control bleeding after a stroke or hemorrhage

-

Treat infections, abscesses, or other neurological conditions

The procedure allows neurosurgeons to directly access the brain safely.

2. Why Is Craniotomy Surgery Needed?

Craniotomy is performed when non-surgical treatments are insufficient or unsafe, including situations like:

-

Brain tumors (benign or malignant)

-

Aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations (AVMs)

-

Traumatic brain injuries with hematomas or swelling

-

Severe brain infections or abscesses

-

Epilepsy surgery for seizure control

-

Intracranial pressure management in stroke or trauma

This surgery allows surgeons to treat, repair, or remove brain lesions while minimizing damage to healthy tissue.

3. How Is a Craniotomy Performed?

Craniotomy is performed under general anesthesia.

Procedure Steps:

-

The scalp is shaved and disinfected.

-

A section of the skull (bone flap) is carefully removed to expose the brain.

-

Surgeons treat the underlying problem - e.g., removing a tumor, clipping an aneurysm, or draining a hematoma.

-

The bone flap is replaced and secured using metal plates and screws, or sometimes a synthetic substitute if needed.

-

The scalp is closed with sutures or staples.

Surgery duration varies from 2 to 6 hours depending on complexity.

4. What Are the Different Types of Craniotomy?

Craniotomy procedures may vary depending on the target area and condition:

-

Standard Craniotomy: Open surgery to access tumors or remove hematomas.

-

Keyhole Craniotomy: Small incision and minimal bone removal, often aided by an endoscope.

-

Supratentorial Craniotomy: Accessing the upper part of the brain (cerebrum).

-

Infratentorial Craniotomy: Accessing the lower brain or cerebellum.

-

Awake Craniotomy: Performed while the patient is awake to monitor brain function during tumor removal.

The neurosurgeon chooses the type based on location, size, and surgical goals.

5. Is Craniotomy Surgery Painful?

During surgery, you will be under general anesthesia and feel no pain.

After the procedure, mild to moderate pain around the scalp incision or headache is common. Pain is usually managed with prescription or over-the-counter analgesics.

Most patients report that discomfort is temporary, gradually improving over the first few weeks of recovery.

6. What Is the Recovery Process After Craniotomy?

Recovery varies depending on the surgery's complexity and the patient's health:

-

Hospital Stay: Usually 3–7 days, sometimes longer for complications.

-

Initial Recovery: Headache, fatigue, scalp swelling, or bruising are common.

-

Rehabilitation: Physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy may be needed, especially if neurological function was affected.

-

Full Recovery: May take weeks to months, depending on the underlying condition and brain healing.

Patients are advised to avoid strenuous activity, heavy lifting, and contact sports during the initial healing phase.

7. What Are the Risks or Complications of Craniotomy?

Craniotomy is generally safe but carries risks such as:

-

Infection at the incision or in the brain

-

Bleeding or hematoma formation

-

Seizures

-

Stroke or neurological deficits

-

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage

-

Cognitive or memory changes

-

Rarely, death

Most complications are preventable with experienced surgeons, ICU monitoring, and proper post-operative care.

8. Who Is a Good Candidate for Craniotomy?

Patients who may benefit from craniotomy include those with:

-

Brain tumors, aneurysms, or AVMs

-

Severe head injuries with bleeding or swelling

-

Epilepsy unresponsive to medication

-

Brain abscesses or infections requiring drainage

-

Skull deformities needing correction

Candidates must be healthy enough for anesthesia, and their medical team will evaluate overall risk factors before surgery.

9. How Long Do Craniotomy Results Last?

Craniotomy addresses the underlying brain problem, so results depend on the condition treated:

-

Tumor removal: Reduces mass effect and may improve neurological function; follow-up imaging is required to detect recurrence.

-

Aneurysm clipping: Permanently reduces rupture risk.

-

Hematoma removal or pressure relief: Often provides lasting improvement in neurological symptoms.

Post-surgery care and medication adherence affect long-term outcomes.

10. What Is the Long-Term Outlook After Craniotomy?

The prognosis after craniotomy depends on:

-

The underlying condition (tumor type, stroke severity, injury extent)

-

Patient age and overall health

-

Timeliness of surgery and post-operative care

With proper treatment and rehabilitation, many patients experience:

-

Improved neurological function

-

Reduced risk of recurrent bleeding or pressure

-

Enhanced quality of life and independence

Regular follow-ups with a neurosurgeon and neurologist are crucial for monitoring recovery and preventing complications.