Introduction to Laminectomies

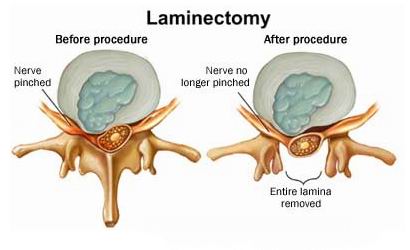

A laminectomy is a surgical procedure performed to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerves by removing part or all of the vertebral "lamina," which is the bony arch forming the back of the spinal canal. The lamina acts like a protective cover for the spinal cord, and in certain medical conditions, this space can become narrowed, resulting in compression of the spinal nerves. Laminectomy is primarily performed to alleviate symptoms caused by spinal stenosis, herniated discs, bone spurs, tumors, or other spinal abnormalities.

The procedure can be performed at different levels of the spine, including the cervical (neck), thoracic (mid-back), and lumbar (lower back) regions, depending on where nerve compression is occurring. Laminectomy aims to relieve pain, restore mobility, improve neurological function, and prevent further deterioration. Modern approaches include both traditional open surgery and minimally invasive techniques, the latter reducing muscle damage, blood loss, and recovery time.

Understanding the role of laminectomy in spinal health is essential because it addresses one of the most common causes of chronic back and limb pain, especially in older adults. By removing the structures compressing the nerves, patients often experience significant improvements in quality of life, including reduced pain, better walking ability, and restored independence. This article explores the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of conditions requiring laminectomy.

Causes and Risk Factors of Laminectomies

Laminectomy is not a disease in itself; it is a surgical treatment for conditions that cause narrowing of the spinal canal or compression of the nerves. The most common cause leading to a laminectomy is degenerative spinal disease, which is usually age-related. As people age, the discs between vertebrae may shrink or herniate, the ligaments may thicken, and bone spurs may develop, collectively reducing the space available for the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Key conditions leading to laminectomy include:

-

Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the spinal canal due to bone overgrowth, thickened ligaments, or disc degeneration. It is the most frequent indication for lumbar and cervical laminectomy.

-

Herniated or Bulging Discs: When the soft tissue of the disc protrudes into the spinal canal, it can press on nerve roots, causing pain, numbness, and weakness.

-

Bone Spurs (Osteophytes): Extra bony growths that develop on vertebrae, often due to osteoarthritis, may encroach on the nerve space.

-

Tumors or Infections: Less commonly, spinal tumors or infections may compress nerves and necessitate decompression.

-

Spinal Injuries or Fractures: Trauma that leads to misalignment or bone fragments in the canal may require surgical relief.

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of requiring a laminectomy include aging, genetic predisposition to spinal degeneration, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and repetitive heavy lifting. Smoking and obesity accelerate spinal degeneration and can impair healing post-surgery. Prior spine surgeries or spinal instability may also increase the risk of nerve compression at adjacent levels, potentially requiring further surgical intervention. It is important to note that not every patient with these conditions will require surgery; laminectomy is usually reserved for those whose symptoms are severe or unresponsive to conservative treatments.

Symptoms and Signs Leading to Laminectomies

Symptoms prompting a laminectomy primarily arise from nerve compression caused by spinal stenosis, herniated discs, or bone spurs. The manifestations depend on the level of the spine affected, but all involve pain, numbness, and functional impairment.

Common symptoms include:

-

Lower Back (Lumbar) Stenosis: Pain radiating to the buttocks, thighs, or legs (sciatica), numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, and difficulty walking. Many patients experience neurogenic claudication, where leg pain worsens with standing or walking and improves with sitting or leaning forward.

-

Neck (Cervical) Stenosis: Neck pain, shoulder or arm pain, numbness, weakness in arms and hands, difficulty with fine motor skills, and in severe cases, gait disturbances or balance issues.

-

Thoracic Stenosis: Mid-back pain, radiating symptoms around the chest or abdomen, which is less common but can be serious if spinal cord compression occurs.

Additional clinical signs may include:

-

Reduced reflexes in affected limbs.

-

Weakness or atrophy of muscles.

-

Sensory loss or altered sensation in arms or legs.

-

Gait instability, difficulty with balance, or frequent tripping.

-

In severe cases, loss of bladder or bowel control (cauda equina syndrome), which requires urgent surgical intervention.

Recognizing these symptoms early and seeking medical evaluation is crucial. The progression of nerve compression can lead to permanent neurological damage if left untreated, making timely diagnosis and intervention vital for maintaining mobility and quality of life.

Diagnosis of Conditions Requiring Laminectomies

Accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of successful treatment for spinal nerve compression. The process begins with a thorough clinical evaluation, including a detailed history of symptoms, physical examination, and assessment of neurological function. Clinicians look for patterns of pain, numbness, weakness, changes in reflexes, and functional limitations that correlate with specific spinal levels.

Diagnostic tools and tests include:

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Provides a detailed view of soft tissues, discs, ligaments, and the spinal canal, and is often the preferred imaging technique.

-

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Excellent for assessing bone abnormalities, bone spurs, and spinal alignment.

-

X-Rays: Helpful in evaluating spinal stability, alignment, and degenerative changes.

-

Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies: Can assess the degree of nerve involvement and differentiate nerve compression from other neurological conditions.

The combination of imaging and clinical findings allows the surgeon to identify the exact location and severity of nerve compression. This evaluation also helps determine whether surgery is necessary or if conservative treatments might be effective. Preoperative assessment also includes evaluating the patient's overall health, comorbidities, and surgical risk factors to optimize outcomes.

Treatment Options Including Laminectomies

Treatment for spinal nerve compression ranges from conservative measures to surgical intervention. Laminectomy is considered when non-surgical treatments fail or when neurological deficits are progressive or severe.

Conservative treatments include:

-

Physical therapy and exercises to strengthen the core and improve flexibility.

-

Pain medications such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen.

-

Epidural steroid injections to reduce inflammation around compressed nerves.

-

Lifestyle modifications, including weight management, posture correction, and ergonomic adjustments.

Laminectomy is recommended when:

-

Pain or neurological symptoms persist despite conservative treatment.

-

There is weakness, numbness, or loss of function in arms or legs.

-

Patients experience difficulty walking, balance issues, or bladder/bowel dysfunction.

Surgical procedure details:

-

The surgeon removes part or all of the lamina to enlarge the spinal canal.

-

Bone spurs or thickened ligaments contributing to compression are also removed.

-

The procedure may be performed using traditional open surgery or minimally invasive techniques, which use smaller incisions and specialized instruments, leading to faster recovery and less tissue trauma.

-

In cases of spinal instability, the surgeon may perform a spinal fusion to maintain alignment and prevent post-surgical complications.

Recovery and outcomes:

-

Most patients experience significant relief of leg or arm pain and improvement in mobility.

-

Hospital stays can range from a few hours (outpatient minimally invasive procedures) to several days for more extensive surgeries.

-

Postoperative rehabilitation is essential to regain strength, flexibility, and functional independence.

Prevention and Management of Spinal Conditions Requiring Laminectomies

Although degenerative spinal changes cannot be entirely prevented, certain strategies can reduce the risk of progression and improve long-term outcomes.

Preventive measures include:

-

Maintaining a healthy weight to reduce stress on the spine.

-

Regular physical activity focusing on core and back strengthening.

-

Avoiding smoking, which accelerates disc degeneration and impairs healing.

-

Practicing good posture, ergonomics, and safe lifting techniques.

-

Early intervention for back pain and spinal discomfort.

Management after surgery:

-

Following a structured rehabilitation program including guided physical therapy.

-

Gradual return to normal activities, avoiding heavy lifting or twisting in the early weeks.

-

Continuing long-term spine care through exercise, flexibility routines, and ergonomic adjustments.

-

Monitoring for recurring symptoms or signs of adjacent segment disease.

Engaging actively in rehabilitation and lifestyle modifications significantly enhances surgical outcomes and long-term quality of life.

Complications of Laminectomies

While laminectomy is generally safe, like any major surgery, it carries potential risks. Complications may be immediate or long-term, and understanding them helps patients make informed decisions.

Possible complications include:

-

Bleeding or hematoma formation.

-

Infection at the surgical site.

-

Injury to nerves or the spinal cord, resulting in weakness, numbness, or paralysis.

-

Cerebrospinal fluid leaks due to dural tears.

-

Blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Long-term risks:

-

Persistent pain or incomplete symptom relief.

-

Spinal instability, sometimes requiring further surgery.

-

Degeneration of adjacent spinal segments leading to recurrent symptoms.

Risk factors for complications include older age, obesity, smoking, pre-existing medical conditions, and the complexity or extent of surgery. However, careful surgical planning, minimally invasive techniques when appropriate, and proper postoperative care can significantly reduce these risks.

Living with the Condition Before and After Laminectomies

Living with spinal nerve compression can profoundly impact daily life. Patients often struggle with chronic pain, mobility limitations, and the emotional stress of declining function. For those undergoing laminectomy, understanding the recovery process and adopting proactive strategies are essential for regaining independence and quality of life.

Before surgery:

-

Pain management through medications, physical therapy, and supportive devices.

-

Adjusting lifestyle and daily activities to minimize strain on the spine.

-

Coping with emotional stress and anxiety related to chronic pain.

After surgery:

-

Gradual return to activity under the guidance of a physical therapist.

-

Following post-operative precautions, including avoiding heavy lifting, bending, or twisting initially.

-

Engaging in long-term spine strengthening and flexibility programs.

-

Maintaining overall health through nutrition, weight management, and avoidance of smoking.

-

Awareness of new or recurring symptoms to seek timely medical advice.

With proper care and rehabilitation, most patients experience significant improvements in pain, mobility, and independence. While spinal health requires lifelong attention, laminectomy often allows patients to return to meaningful daily activities, work, and hobbies with reduced pain and improved quality of life.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Laminectomy

1. What is a laminectomy?

A laminectomy is a spinal surgical procedure in which part or all of the vertebral "lamina" (the back arch of a vertebra) is removed to enlarge the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots. This is done to alleviate symptoms from nerve compression such as in spinal stenosis.

2. Why and when is laminectomy recommended?

Surgeons may recommend a laminectomy when non-surgical treatments (physiotherapy, medications, injections) have failed and you have:

-

Significant leg or arm pain, numbness or weakness due to nerve root compression.

-

Difficulty walking or standing because of spinal canal narrowing (neurogenic claudication).

-

Loss of bladder or bowel control in severe cases.

Imaging (MRI/CT) and clinical examination help determine the indication.

3. How is the laminectomy procedure performed?

The general surgical steps include:

-

Under general anesthesia, an incision is made over the affected vertebrae.

-

Muscles and ligaments are moved aside to expose the spinal canal.

-

The lamina (and possibly the spinous process or ligamentum flavum) is removed, and any bone spurs or disc fragments compressing nerves may also be removed.

-

In some cases, a fusion or instrumentation may be added if there's instability.

4. What types of laminectomy are there and where in the spine can it be done?

-

Lumbar laminectomy (lower back) — most common, for leg symptoms and walking difficulty.

-

Cervical laminectomy (neck) — for arm symptoms or spinal cord compression.

-

Thoracic laminectomy (mid-back) — less common but used in specific cases.

Techniques can vary between open surgery and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) depending on the case.

5. What are the benefits of undergoing a laminectomy?

Key potential benefits include:

-

Relief of nerve compression symptoms (less leg/arm pain, less numbness or weakness).

-

Improved walking ability, reaching or daily functions when nerves were limiting.

-

For many patients, a significant improvement in quality of life and ability to perform daily activities.

6. What are the risks and possible complications?

As with any surgery, there are risks. Potential complications include:

-

Infection, bleeding, or blood clots (deep vein thrombosis)

-

Nerve injury resulting in weakness, numbness or even paralysis (rare)

-

Dural tear (spinal fluid leak)

-

Persistent pain, or recurrence of symptoms due to underlying disease progression

-

Spinal instability if a large part of lamina or facets are removed without stabilisation

7. What is the recovery process like and how long will it take?

Recovery varies based on the region of surgery and whether a fusion was done. General guideline:

-

Hospital stay: often 1-2 nights for simple decompression.

-

Early mobilisation: patients often begin walking the day of or next day.

-

Return to light activities: within a few weeks.

-

Full return to unrestricted activities: often around 3 months; if fusion is done, it may take 6 months or more.

8. Will the surgery cure my back pain?

Not always. A laminectomy is most effective for nerve-compression symptoms (e.g., leg pain, numbness) due to spinal stenosis or disc fragment. It may not fully resolve axial back pain (pain from the spine itself, muscles, joints, arthritis) especially if degeneration is widespread. It's important to understand what symptoms are being targeted.

9. Are there lifestyle modifications after surgery and what restrictions apply?

Yes. After surgery, patients are typically advised to:

-

Avoid heavy lifting, bending or twisting for several weeks (often first 4-6 weeks).

-

Use proper body mechanics, posture, and gradually increase activity with supervision.

-

Continue physiotherapy or prescribed exercises for strengthening and flexibility.

-

Maintain a healthy weight, avoid smoking (which impairs healing) and moderate prolonged sitting/standing.

10. How do I choose a reliable surgeon and what questions should I ask?

When evaluating for laminectomy, you should ask:

-

What is your experience with laminectomy in my specific spine region (lumbar/cervical)?

-

What exact goal is the surgery aiming to achieve in my case (which symptoms will it relieve)?

-

Will you also need to perform fusion/instrumentation, and why?

-

What is the expected recovery timeline and what restrictions will I have?

-

What are the risks in my case, and what is the success rate?

By addressing these questions, you can ensure you have an informed discussion and realistic expectations.