Introduction to PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus) Ligation

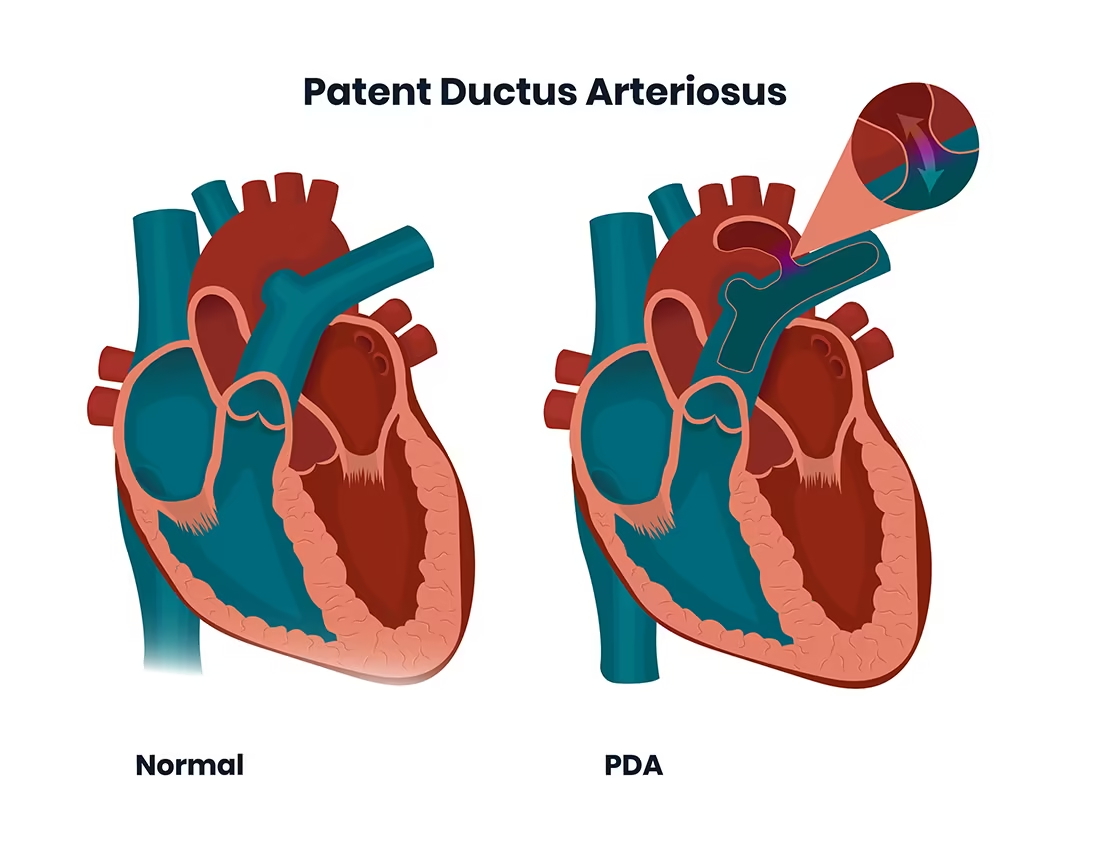

The ductus arteriosus is a fetal blood vessel connecting the pulmonary artery to

the descending aorta, allowing most of the right-ventricular output in utero to

bypass the non-functioning fetal lungs. After birth, with lung expansion and a

rise in oxygen levels, the ductus normally constricts and eventually becomes the

ligamentum arteriosum. However, when this vessel remains patent (open) beyond

the neonatal period or fails to close in a preterm infant, this is known as

patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). A persistently open ductus creates a

left-to-right shunt (aorta → pulmonary artery), increasing pulmonary blood flow,

overloading the left heart, and risking long-term complications such as

pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, and growth failure.

When medical management (such as NSAID-based closure in infants) fails, or when

the PDA is large or causing significant hemodynamic burden, surgical or device

closure becomes necessary. “PDA ligation” refers to the surgical technique of

tying off, clipping, or otherwise closing the ductus via a thoracotomy,

thoracoscopic or sometimes catheter-based approach. The goal is elimination of

the pathological shunt, mitigation of cardiac strain, and prevention of further

complications.

Over recent decades, surgical ligation of PDAs has evolved. In paediatric cardiac surgery, minimally invasive approaches, bedside ligation in neonatal ICUs for very low birth-weight infants, and hybrid techniques have improved outcomes and reduced morbidity. Adult patients with untreated PDA also may require surgical ligation or device closure if the shunt is significant. Surgical ligation remains a vital option especially when percutaneous device closure is not feasible (for example in calcified ducts, unusual anatomy or other contra-indications).

Causes and Risk Factors of PDA Requiring Ligation

The main causes and risk factors for patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) requiring ligation (surgical closure) include prematurity, genetic syndromes, maternal infections, family history, and environmental conditions that interfere with normal ductus closure at birth. Ligation is usually performed when the PDA is large, persists despite medical therapy, or causes significant cardiovascular symptoms.

Causes

PDA arises when the normal physiological closure of the ductus arteriosus does not occur. Contributing factors include:

-

Prematurity: The most common cause, because preterm infants often lack the maturity of smooth muscle in the ductus and have higher prostaglandin levels.

-

Genetic syndromes: Conditions such as Down syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, and other congenital heart disease associations increase PDA risk.

-

Infections or inflammation: Maternal rubella infection, chorioamnionitis, or neonatal sepsis may delay closure.

-

Other cardiac anomalies: Some congenital heart defects require the ductus to remain open temporarily; if closure occurs prematurely, it may cause problems-but later may remain open when it should not.

-

Increased prostaglandin levels or altered oxygenation: Conditions that delay the postnatal drop in prostaglandins can keep the ductus open.

Risk Factors for Needing Ligation

Not all PDAs require surgical ligation; ligation is considered when the shunt is “hemodynamically significant” or medical closure fails. Factors increasing the likelihood of needing ligation include:

-

Larger ductal diameter (studies show, for example, diameter > 2.0 mm in very low-birth-weight infants correlates with surgical ligation).

-

Low gestational age and low birth weight in neonates.

-

Failure of pharmacologic closure (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) or contraindications to such therapy.

-

Presence of clinical complications from the shunt: heart failure, pulmonary over-circulation, feeding intolerance, necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) in preemies.

-

In adults or older children: prolonged un-closed PDA may lead to calcification, pulmonary hypertension, and thus require surgical ligation rather than device closure.

Understanding these causes and risk factors helps clinicians decide the timing and method of intervention-and helps families understand why surgical ligation may be chosen.

Symptoms and Signs of PDA Requiring Ligatio

Symptoms and signs indicating the need for PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus) ligation generally relate to the size of the ductus, its hemodynamic significance, and the resulting impact on the heart and lungs.

In Neonates and Infants

When a PDA causes a significant left-to-right shunt, symptoms and signs may include:

-

Tachypnoea (rapid breathing), respiratory distress or increased work of breathing from pulmonary overcirculation.

-

Difficulty feeding, poor weight gain or failure to thrive.

-

Frequent lung infections or pneumonia due to excess pulmonary blood flow.

-

Heart failure signs: hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), oedema, sweating during feeds, tachycardia.

-

On examination: a continuous “machinery” murmur (often heard best at the left infraclavicular area), bounding peripheral pulses, widened pulse pressure (difference between systolic and diastolic pressure), hyperdynamic pre-cordium, left heart enlargement on imaging.

In Older Children or Adults

In less dramatic cases or when the PDA is moderate:

-

Exercise intolerance or fatigue.

-

Palpitations, shortness of breath, or recurrent respiratory infections.

-

Signs of long-standing volume overload such as left ventricular enlargement, atrial arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension.

-

In adult untreated PDAs: risk of Eisenmenger syndrome (reversal of shunt to right-to-left, causing cyanosis) or high pulmonary vascular resistance.

When to Consider Ligation

Symptoms and signs indicating that a PDA is “hemodynamically significant” (and thus likely to require closure) include: large shunt volume on echocardiography, left atrial or left ventricular enlargement, pulmonary hypertension, recurrent respiratory issues, failure to thrive, or complications like NEC in preterm infants. The decision to ligate is based on both clinical signs and imaging/echocardiographic evidence.

Diagnosis of PDA and Pre-Ligation Evaluation

Diagnosis of PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus) and pre-ligation evaluation use a combination of clinical findings, imaging (especially echocardiography), and laboratory markers to confirm the presence and significance of the ductus, assess its hemodynamic impact, and guide timing and need for surgical closure.

A careful diagnostic evaluation precedes any decision for PDA ligation. The key components are:

Clinical and Physical Examination

Detailed history (prematurity, infections, feeding/respiratory issues, congenital heart disease) and physical exam (heart murmur, bounding pulses, signs of heart failure, hepatomegaly, lung signs) provide initial clues.

Imaging and Cardiac Investigations

-

Echocardiography (transthoracic): Primary diagnostic tool. It assesses ductal size, shunt direction/velocity, left atrial and left ventricular enlargement, pulmonary artery pressure estimates, and associated heart defects.

-

Chest X-Ray: May show cardiomegaly, increased pulmonary vascular markings, and signs of pulmonary oedema.

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG): May show left heart strain or arrhythmia but is less specific.

-

Cardiac catheterisation / angiography: Rarely needed purely for diagnosis in uncomplicated cases, but used in older children/adults or when anatomy is complex or device closure is planned.

Laboratory and Other Assessments

-

Assessment of heart failure markers, renal function, oxygenation, and other comorbidities if present.

-

In the preterm infant: assessment of feeding, ventilator status, presence of NEC or IVH-which may influence timing of ligation.

Pre-Ligation Planning

Prior to surgical ligation, key considerations include: ductal anatomy and size, associated congenital heart lesions, pulmonary vascular resistance (especially in older children/adults), age and weight of the patient (especially neonates), presence of infection or organ immaturity, pre-operative optimisation (respiratory, nutritional), location of surgical approach (thoracotomy vs thoracoscopic vs bedside NICU ligation), and post-operative care planning. The diagnostic work-up guides the surgical method and timing to achieve best outcomes.

Treatment Options for PDA - Focus on Ligation

The main treatment options for patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) focus on achieving closure to prevent heart and lung complications. While some PDAs close on their own or with medication, ligation (surgical closure) is a proven, highly effective approach-especially for symptomatic, large, or treatment-resistant PDAs.

Medical (Non-Surgical) Options

-

Pharmacologic closure: In preterm neonates, first-line treatment often involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as indomethacin or ibuprofen, or acetaminophen in some centres. These agents inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, promoting ductal closure.

-

Conservative management: Some small PDAs in otherwise healthy term infants may be monitored, as spontaneous closure may still occur. The decision to treat is based on hemodynamic significance.

Device Closure

In children or adults with favourable anatomy, transcatheter device closure (coil, Amplatzer duct occluder, etc.) is often preferred because it is less invasive than surgery. However, not all PDAs are amenable to device closure (e.g., calcified ductus, unusual shape, large size, very small or premature infants).

Surgical Ligation (Focus of This Section)

When medical or device closure is not possible or has failed, and when the PDA is deemed hemodynamically significant, surgical ligation is indicated. Key features:

-

Timing: In neonates, especially preterm, early ligation (within the first 10 days of life) in selected infants with hemodynamically significant PDA may reduce complications such as NEC, IVH, prolonged ventilation.

-

Approach: Typically via left posterolateral thoracotomy (third or fourth intercostal space) in the infant/child. For adults or calcified ducts, sternotomy or cardiopulmonary bypass may be required.

-

Technique: After incision and exposure, the ductus arteriosus is dissected free from surrounding structures (aorta, pulmonary artery, recurrent laryngeal nerve, thoracic duct, left superior intercostal vein). A clamp is placed, and the duct is ligated (tie with suture) or clipped. Some surgeons divide and oversew the duct but ligation alone is common. In neonates, metal clips may be used to reduce dissection risks.

-

Postoperative care: Chest tube placement, monitoring of haemodynamics, ventilation, removal of drain when stable. Hospital stay may be 2-4 days in uncomplicated cases (longer in neonates).

-

Outcomes: High success rates with closure of shunt, improvement of pulmonary over-circulation, reduction in ventilator days, better feeding and growth in infants, and decreased pulmonary hypertension in older children/adults.

Decision-Making: Why Ligation?

Surgery is chosen because: medical therapy failed or is contraindicated (renal impairment, necrotising enterocolitis, bleeding risk), the PDA anatomy is not suitable for device closure, or the patient is very small/preterm where device closure is impractical. Furthermore, when the shunt is large and causing organ damage (lungs, heart, kidneys, gut) timely ligation may reduce morbidity. In preterm infants, data support earlier ligation rather than delay after prolonged exposure.

Prevention and Long-Term Management After PDA Ligation

After PDA ligation, prevention and long-term management require careful follow-up, early identification of rare complications, lifestyle considerations, and periodic cardiac assessment to ensure optimal health and reduce risks for late sequelae.

Prevention

-

In preterm infants: Minimising risk of PDA persistence includes optimal prenatal & perinatal care (limiting chorioamnionitis, optimising ventilation and oxygenation after birth), early screening for PDA, and timely medical therapy when indicated.

-

In term infants/children: Avoidance of risk factors for delayed closure (infections, high prostaglandin states) and early recognition of murmurs/heart symptoms so that closure occurs before irreversible pulmonary vascular disease.

Long-Term Management Post-Ligation

After successful ligation:

-

Follow-up echocardiography to confirm closure, assess ventricular size/function, rule out residual shunt or complications.

-

Monitor growth and development especially in preterm infants: feeding, weight gain, respiratory status, neurodevelopmental milestones.

-

Cardiac follow-up: In older children/adults treated, assess for pulmonary hypertension resolution, arrhythmias, residual heart changes.

-

Lifestyle advice: Healthy diet, physical activity as permitted, avoiding undue strain in early postoperative period.

-

Surveillance for complications: Although rare, recognize signs such as recurrent shunt, residual duct, late pulmonary vascular disease.

-

Multi-disciplinary care: Especially in preterm infants who needed ligation, coordinated follow-up including neonatology, cardiology, developmental paediatrics, and wherever needed physical and occupational therapy.

Prevention of long-term complications is effected by timely closure, minimising shunt exposure, and ensuring optimal post-operative recovery and development.

Complications of PDA Ligation

While surgical ligation is generally safe and effective, there are potential complications:

Early/Postoperative Complications

-

Bleeding: Injury to aorta or pulmonary artery during dissection may cause serious haemorrhage.

-

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury: Leading to hoarseness, vocal cord paresis.

-

Diaphragmatic paralysis: Via phrenic nerve or via injury to the left hemidiaphragm-especially in neonates.

-

Chylothorax: Injury to thoracic duct leads to lymphatic leak into chest.

-

Arrhythmias or hypotension: Post-ligation hypotension can occur in preterm infants due to sudden changes in load.

-

Infection, wound complications, pneumothorax, pleural effusion.

Late or Long-Term Complications

-

Residual or recurrent shunt: Rare, but may require further intervention.

-

Pulmonary hypertension that developed before closure may persist. In older patients, irreversible pulmonary vascular disease may limit benefit.

-

Developmental or neurodevelopmental disorders in preterm infants: Some studies suggest association of very early ligation with neurodevelopmental issues, although cause and effect remain debated.

-

Scarring or chest wall deformity from thoracotomy in infants, though minimally invasive approaches reduce this risk.

Risk-Benefit Discussion

While risks exist, for hemodynamically significant PDAs, the benefits of ligation (reduced lung injury, improved growth/feeding, better cardiac outcomes) often outweigh risks. Optimal timing and surgical expertise minimise complications. In very low birth-weight preterm neonates, decision-making is nuanced given their vulnerability and co-morbidities.

Living with PDA and Life After Ligation

Life after PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus) ligation-whether by surgery or device closure-is typically excellent, with most individuals achieving a normal or nearly normal quality of life, rapid return of energy, and complete resolution of symptoms. Ongoing care and adaptation are usually minimal, particularly when closure is done in infancy or early childhood.

Before Ligation

Children or infants with untreated significant PDAs may experience difficulty feeding, frequent respiratory infections, fatigue, growth delay, heart murmur detection, and anxious parents. They may have repeated hospitalisations for lung issues or heart failure. For older children/adults, exercise intolerance, arrhythmia risk, and pulmonary hypertension may emerge.

Recovery and Life After Ligation

-

In straightforward term infants, hospital stay may be brief (2-4 days) and return to normal activities occurs rapidly. In preterm infants or those with co-morbidities, more extended recovery may be necessary.

-

Post-operative care includes monitoring for pain, breathing, wound healing, and ensuring feeding and growth. Parents/caregivers are instructed on incision care, recognising signs of infection, how to monitor heart/respiratory symptoms, and follow-up appointments.

-

Over the long term, many children lead normal lives with normal cardiac function, normal growth and development, and no further symptoms. Cognitive and developmental outcomes are best when PDA closure is timely and comorbidities managed.

-

For older children/adults treated for PDA, follow-up focuses on cardiac status, lung pressures, arrhythmia surveillance, and lifestyle guidance such as moderate exercise, healthy diet, avoiding smoking, and managing other cardiovascular risk factors.

Patient and Family Education

-

Explain what a PDA is, why closure was necessary, how surgery was performed, expected outcomes, and what to expect during recovery.

-

Emphasise signs to watch for after surgery (fever, incision swelling, breathing difficulty, poor feeding).

-

Promote adherence to follow-up visits and cardiac imaging as recommended.

-

Encourage normal activity levels appropriate for the child's age once the surgeon gives the green light; reassure families about long-term prognosis.

-

Provide emotional support: surgery on the heart vessel-even minor-can be stressful for families; connecting with support groups or other families may help.

Long-Term Outlook

The prognosis after successful PDA ligation is excellent in most cases. Critical factors for optimal outcomes include the timing of closure (earlier is generally better in hemodynamically significant cases), the absence of irreversible pulmonary vascular disease, and absence of significant associated congenital heart defects. With timely ligation, risk of growth delay, respiratory complications, congestive heart failure and pulmonary vascular degeneration decreases significantly. In older children/adults who underwent closure, reduction in pulmonary pressure, improvement in heart function, and better quality of life have been documented.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus) Ligation

1. What is Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)?

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) is a congenital heart defect in which a small blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus fails to close naturally after birth. This vessel connects the pulmonary artery to the aorta in fetal circulation to bypass the lungs. Normally, it closes within the first few days of life, but in PDA, it remains open, causing abnormal blood flow between the aorta and pulmonary artery. Left untreated, PDA can result in increased pulmonary blood flow, heart enlargement, heart failure, or lung complications.

2. Why is PDA ligation necessary?

PDA ligation is a surgical procedure designed to close the patent ductus arteriosus, restoring normal circulation. It is required when:

-

The PDA is large or symptomatic, causing fatigue, shortness of breath, poor feeding, or failure to thrive in infants.

-

Medication therapy (like indomethacin or ibuprofen in preterm infants) fails to close the PDA.

-

There is risk of serious complications, such as pulmonary hypertension, endocarditis, heart failure, or left ventricular enlargement.

-

Long-standing PDA can lead to irreversible heart or lung damage, making early surgical closure essential for long-term health.

Ligation eliminates abnormal blood flow, improves cardiac function, and prevents life-threatening complications.

3. Who is a candidate for PDA ligation?

PDA ligation is suitable for:

-

Infants and children with significant or symptomatic PDA

-

Premature babies where PDA is causing respiratory distress or feeding difficulties

-

Patients with cardiomegaly or pulmonary over-circulation due to persistent PDA

-

Children at high risk of endocarditis or other PDA-related complications

Candidates undergo detailed evaluation including echocardiography, Doppler studies, chest X-rays, and sometimes cardiac catheterization to assess the size and hemodynamic impact of the PDA.

4. How is PDA ligation performed?

PDA ligation is performed under general anesthesia. The surgical steps include:

-

Incision: Typically a small left thoracotomy incision is made between the ribs to access the PDA.

-

Exposure: The ductus arteriosus is carefully dissected and separated from surrounding structures, including the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

-

Ligation: The PDA is tied off (ligated) using sutures or surgical clips to stop abnormal blood flow.

-

Closure: The incision is closed in layers, and the patient is moved to recovery for monitoring.

In some centers, minimally invasive thoracoscopic PDA ligation is performed, reducing recovery time and scarring.

5. What are the benefits of PDA ligation?

-

Restores normal blood circulation, reducing strain on the heart and lungs

-

Relieves symptoms like fatigue, rapid breathing, poor feeding, and growth delay

-

Prevents long-term complications including pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, or endocarditis

-

Improves overall growth and development in infants and children

-

Offers a high success rate with most PDAs permanently closed after surgery

PDA ligation provides both immediate and long-term improvements in cardiac and respiratory health.

6. Is PDA ligation painful?

During the procedure, general anesthesia ensures the child feels no pain. After surgery, mild pain and discomfort are expected:

-

Soreness or tenderness at the chest incision

-

Bruising or mild swelling around the surgical site

-

Temporary irritability or fussiness in infants

Pain is managed with age-appropriate medications, and most children recover comfortably within a few days to a week.

7. What are the risks and complications of PDA ligation?

PDA ligation is generally safe, but potential complications include:

-

Bleeding at the surgical site

-

Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing temporary hoarseness

-

Infection at the incision or in the lungs

-

Residual PDA if closure is incomplete, which may require a second procedure

-

Rare complications such as heart rhythm disturbances or pleural effusion

Careful surgical technique, proper patient selection, and post-operative monitoring reduce these risks significantly.

8. What is the recovery process after PDA ligation?

Recovery varies by age and procedure type:

-

Hospital stay: Usually 1-3 days, depending on the child's condition

-

Activity restrictions: Avoid strenuous activity and rough play for several weeks

-

Incision care: Keep the surgical site clean, dry, and monitor for redness or swelling

-

Follow-up: Echocardiography is performed to confirm complete PDA closure

-

Feeding and hydration: Normal feeding is usually resumed within a day or two, and hydration is encouraged

Most children return to normal activity and growth patterns within 1-2 weeks.

9. How successful is PDA ligation?

PDA ligation has a success rate of over 95-98%, with most PDAs permanently closed after surgery. Residual PDAs are uncommon and can often be addressed using catheter-based closure techniques. Long-term outcomes are excellent, with normal heart function and no recurrence of symptoms in the vast majority of patients.

10. How much does PDA ligation cost, and is it covered by insurance?

The cost depends on:

-

Hospital and surgeon fees

-

Anesthesia and operating room charges

-

Post-operative care and follow-up imaging

PDA ligation is considered medically necessary, and most insurance plans cover the procedure, including hospitalization and follow-up care. Cosmetic or elective procedures are generally not covered. Patients should verify coverage, co-pays, and out-of-pocket expenses with their insurance provider prior to surgery.