Introduction to Prostate Biopsy

A prostate biopsy is a minimally invasive diagnostic procedure performed to obtain tissue samples from the prostate gland for microscopic examination. The prostate is a walnut-sized gland located below the bladder and surrounding the urethra in males; its primary function is to produce seminal fluid that nourishes and transports sperm. A biopsy becomes necessary when screening tests such as a raised prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level or abnormal findings on a digital rectal examination (DRE) raise suspicion of prostate cancer or other prostate pathology.

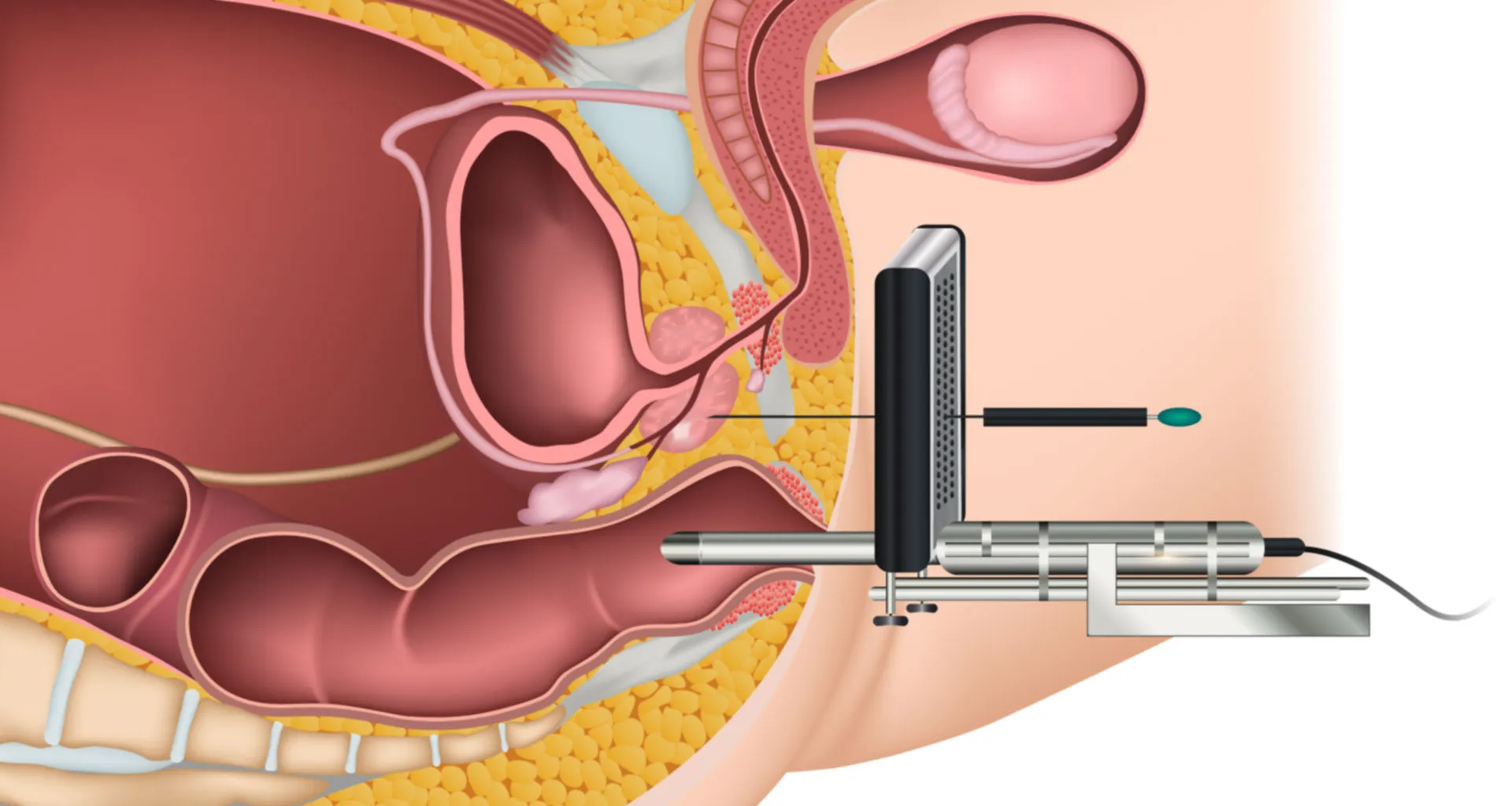

In a typical prostate biopsy, small cylinders ("cores") of prostate tissue are removed using a thin, spring-loaded needle guided by imaging-commonly transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) or, increasingly, MRI/ultrasound fusion. The samples are then sent to a pathology lab for detailed analysis including histology, grading (Gleason score), and sometimes molecular testing.

Modern practice emphasizes careful patient selection, preparation (including antibiotic prophylaxis, cessation of blood-thinners if required), and risk counselling. While the procedure carries some risk-such as bleeding and infection-these risks are well documented and manageable when protocols are followed.

For many men, the prostate biopsy represents a critical step in distinguishing benign from malignant prostate disease, determining the tumour's aggressiveness, and guiding subsequent treatment decisions. As such, understanding the procedure-its indications, process, risks, and post-care-is essential for both patients and clinicians.

Causes and Risk of Prostate Biopsy

A prostate biopsy is done when tests suggest a significant chance of prostate cancer, and like any invasive test it carries some risks, though serious complications are uncommon when done in experienced hands. Understanding both the medical reasons for the biopsy and the potential side effects helps in deciding whether and when to proceed.

Why is a prostate biopsy done?

A biopsy is recommended when preliminary investigations suggest an elevated risk of prostate cancer or other significant prostate disease. Some of the key triggers for considering a biopsy include:

-

Elevated PSA levels beyond expected for age and prostate volume.

-

Abnormal findings on a digital rectal exam (DRE), such as nodules, asymmetry, or induration of the prostate.

-

Suspicious imaging findings, for example on multiparametric MRI of the prostate, showing areas of concern.

-

Persistent or rising PSA levels in spite of previous negative biopsy or benign pathology.

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of requiring a biopsy

Several risk factors increase the probability of finding prostate cancer on biopsy and therefore help guide decision-making:

-

Older age (prostate cancer incidence increases with age).

-

Family history of prostate cancer (first-degree relative).

-

African descent (higher incidence and aggressiveness).

-

High PSA density or rapid PSA velocity (increase in PSA over time).

-

Prior abnormal biopsy findings (such as high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, atypical small acinar proliferation).

-

Findings on MRI (e.g., PI-RADS 4/5 lesions) suggesting higher risk.

Risks associated with the biopsy procedure

Because a biopsy involves penetrating the prostate gland, there are some associated procedure-related risks:

-

Bleeding: blood can appear in urine, stool or semen after the biopsy.

-

Infection: though uncommon, urinary tract infections or prostate infections may occur. Rates of infection after some transrectal biopsies have been reported at 1-2%.

-

Urinary retention or difficulty urinating post-procedure.

-

Discomfort or pain in the biopsy region.

-

Rarely, significant bleeding requiring intervention.

In sum: while the biopsy itself is a diagnostic tool, the decision to perform it is based on weighing the risk of underlying prostate cancer against procedural risks and patient factors.

Symptoms and Signs of Prostate Biopsy

This heading can be somewhat confusing, because a prostate biopsy is a procedure rather than a disease. However, this section can cover the indications for a biopsy (i.e., symptoms and signs that lead to biopsy) as well as what patients can expect during and after the biopsy.

A. Symptoms and signs prompting biopsy

Patients may present with:

-

Elevated PSA blood test without symptoms.

-

Abnormal DRE findings (e.g., a palpable nodule or asymmetry of the prostate).

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS): difficulty urinating, increased frequency, weak stream, though these are often from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) rather than cancer specifically.

-

Hematuria (blood in urine) or hematospermia (blood in semen), though these are less specific.

-

Suspicious imaging findings on prostate MRI or ultrasound.

These findings lead the urologist to recommend a biopsy to rule in or out malignancy.

B. Signs during and after biopsy

During the biopsy procedure, the clinician may observe or anticipate:

-

Use of ultrasound or MRI-fusion guidance to visualise the prostate.

-

Local anaesthesia administration followed by insertion of biopsy needle(s).

-

Multiple tissue cores being taken (often 10-12 or more).

-

Possible transient pain or pressure sensation when needle fired.

After the procedure, patients may notice:

-

Mild rectal or perineal discomfort for 24-48 hours.

-

Blood in urine or stool for a few days, and blood-tinged semen for up to several weeks.

-

Slight swelling or bruising in perineal area.

-

Rarely, difficulty urinating or need for catheter.

It is important that patients are informed about expected post-biopsy signs and warning signs of complications (fever, inability to urinate, heavy bleeding) so they can seek timely care.

Diagnosis of Prostate Biopsy

Here we cover how prostate biopsy fits into the diagnostic algorithm for prostate cancer and how results are interpreted.

A. Diagnostic pathway

-

Initial screening/tests: PSA measurement, DRE, possibly prostate MRI (multiparametric) to localise suspicious areas.

-

Decision to biopsy: Based on elevated PSA, abnormal DRE, MRI findings, or persistent concern despite previous negative tests.

-

Biopsy procedure: Typically guided by TRUS or MRI/ultrasound fusion, cores taken from prostate zones.

-

Pathology assessment: Tissue cores are examined by a pathologist. They determine:

-

Presence or absence of cancer.

-

If cancer present: Gleason score/grade group, tumour volume, margins and other prognostic features.

-

If no cancer: may detect atypical cells, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or benign findings.

-

-

Post-biopsy follow-up: If cancer found, discussion of treatment options. If no cancer, ongoing surveillance or repeat biopsy may be considered if suspicion remains.

B. Newer diagnostic enhancements

-

MRI/Ultrasound fusion biopsy: Improves detection of significant cancers and reduces over-diagnosis of indolent lesions.

-

Targeted plus systematic cores: Combining targeted sampling of MRI lesions with systematic sampling increases accuracy.

-

Genomic and molecular markers: Growing role in refining risk stratification though not yet routine in all settings.

C. Interpretation of results

-

A negative result reduces likelihood of cancer but does not rule it out-clinician may recommend continued surveillance if risk remains.

-

A positive result leads to staging, Gleason grading, and treatment planning.

-

Uncertain findings (atypical cells) may prompt repeat biopsy or closer monitoring.

Thus, the prostate biopsy is a pivotal diagnostic moment that launches the definitive path of either treatment or surveillance.

Treatment Options of Prostate Biopsy

Again, this heading is slightly mis-labelled-since a biopsy is a diagnostic procedure rather than a treatment. However, in the context of your blog structure, this section can cover treatment decisions following biopsy and how the biopsy outcome influences management.

A. If cancer is detected

Based on biopsy results a variety of treatment pathways may be considered:

-

Active Surveillance / Watchful Waiting: For low-risk prostate cancer (low Gleason score, low volume, slow PSA rise), regular monitoring rather than immediate intervention may be chosen.

-

Radical Treatment Options:

-

Radical prostatectomy (surgical removal of the prostate).

-

Radiation therapy (external beam, brachytherapy).

-

Focal therapy (HIFU, cryotherapy) in selected cases.

-

-

Combination Therapies: In higher-risk disease, multimodal treatment including surgery + radiation + androgen-deprivation therapy may be recommended.

-

Individualised Decision-Making: The biopsy result (Gleason score, tumour volume, location), patient age, comorbidities, life expectancy and preferences guide the choice of treatment.

B. If biopsy is negative or shows benign findings

-

Continue surveillance: monitor PSA levels, repeat DRE, consider MRI if suspicion persists.

-

If MRI or other risk markers remain concerning, a repeat biopsy may be warranted (perhaps using MRI-fusion technique) to ensure no cancer was missed.

C. Pre- and post- biopsy procedural care

Though not a treatment of the biopsy itself, preparation and after-care are integral:

-

Pre-procedural antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce infection risk.

-

Stop or adjust blood thinners as guided by physician to reduce bleeding risk.

-

Post-biopsy instructions: rest, avoid heavy lifting, observe for complications.

In summary: the prostate biopsy informs the next steps-whether active monitoring or definitive therapy-so its role is more diagnostic than therapeutic, but intimately linked to treatment planning.

Prevention and Management of Prostate Biopsy

A prostate biopsy itself is not something you "prevent" if it is clearly needed, but unnecessary biopsies can often be avoided, and the risks of a needed biopsy can be reduced and managed. Prevention here mainly means avoiding over-testing and using better imaging and risk tools, while management focuses on preparation, technique, and after-care.

A. Prevention (in terms of minimising complications of biopsy)

While one cannot "prevent" the need for biopsy when indicated, one can minimise risks and complications:

-

Administer antibiotic prophylaxis and bowel preparation to reduce infection risk.

-

Use of transperineal biopsy approaches rather than transrectal in suitable patients to reduce infection risk.

-

Stopping blood-thinning medications (when safe) prior to biopsy to reduce bleeding.

-

Good antiseptic technique, bowel cleansing, and appropriate patient counselling.

-

Monitoring for and early management of urinary retention, haematuria or other symptoms post-procedure.

B. Post-Biopsy Management

-

Provide clear instructions about expected post-procedure symptoms (blood in urine/semen, mild discomfort) and when to seek help.

-

Encourage hydration, avoid heavy physical exertion for 24-48 hours.

-

Follow-up to review pathology and discuss next steps based on results.

-

If infection occurs: prompt antibiotic therapy; if urinary retention: catheter insertion and urology referral.

-

Monitor PSA levels and other relevant markers if biopsy is negative but suspicion remains.

C. Patient education and shared decision-making

-

Educate patients before biopsy about why it is recommended, what to expect, benefits vs risks.

-

Discuss options if biopsy is positive: active surveillance vs intervention.

-

Provide psychological support-biopsy can cause anxiety about cancer risk and complications.

In sum: Prevention and management here focus on safe procedural execution, complication minimisation, and post-procedural follow-through.

Complications of Prostate Biopsy

It is vital to inform patients about potential complications-even though many are minor-and how to manage or avoid them.

A. Common complications

-

Bleeding: blood in urine (hematuria), stool (rectal bleeding), or semen (hematospermia). Usually self-limited.

-

Pain or discomfort: mild rectal/perineal pain for 24-48 hours.

-

Urinary retention: occasionally after biopsy, especially in men with large prostates.

B. Less common but serious complications

-

Infection: urinary tract infection, prostatitis, sepsis. Some studies report up to ~1-2% infection rate in transrectal biopsies.

-

Severe bleeding or haematoma: though rare, may require hospitalisation.

-

Erectile dysfunction or ejaculatory changes: rare and typically transient.

-

False negative or missed cancer: biopsy may not sample the tumour, leading to continued disease despite negative result; follow-up is critical.

C. Long-term considerations

-

Repeated biopsies may increase risk of complications.

-

Psychological stress: anxiety about results and future surveillance.

D. Management of complications

-

Bleeding: usually resolves; if persistent or heavy, seek medical advice.

-

Infection: prompt antibiotic treatment; hospitalisation if systemic signs.

-

Urinary retention: catheterisation, urology referral.

-

Negative biopsy but ongoing suspicion: consider MRI, repeat biopsy.

Understanding these risks and measures helps ensure the biopsy process remains as safe as possible.

Living with the Condition of Prostate Biopsy

This section focuses on what patients should know about life after a prostate biopsy and how to handle the potential outcomes and follow-up.

A. Immediately after biopsy

-

Expect mild discomfort, blood in urine/semen for days to weeks.

-

Avoid strenuous physical activity for 24-48 hours; resume normal activities cautiously.

-

Follow instructions from your urologist: antibiotics, catheter care if needed, monitoring for fever or urinary difficulty.

B. Interpreting and coping with results

-

Negative result: While reassuring, continued monitoring may be advised because no test is perfect and repeat biopsy might be needed if suspicion remains.

-

Positive result (cancer detected): It triggers a detailed discussion of treatment options-active surveillance vs surgery vs radiation vs combinations-and what is best for your health, age, comorbidities, and preferences.

-

Atypical findings: May require further investigation, repeat biopsy, or enhanced imaging.

C. Long-term follow up and wellness

-

Keep regular PSA tests, DREs, and imaging as guided.

-

Maintain a healthy lifestyle: balanced diet, exercise, weight control, limit alcohol, no smoking.

-

Monitor urinary and sexual function: changes may occur from prostate disease or treatments.

-

Psychological and emotional health: the experience of biopsy, possibility of cancer, or treatment side-effects can impact mood, so access to counselling/support groups may be helpful.

D. When further testing or treatment is required

-

If biopsy is positive: attend oncology/urology appointments, discuss risks/benefits of each treatment path.

-

If biopsy is negative but PSA rises or imaging is suspicious: your doctor may recommend repeat MRI, active surveillance, or another biopsy.

-

Communicate openly with your healthcare team about any new urinary symptoms, bleeding, pain, or sexual concerns.

E. Quality of life considerations

-

Many men experience minimal impact from the biopsy itself and go on to lead normal lives.

-

If subsequent treatments are required (for cancer), those may carry additional lifestyle implications (urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, radiation side-effects) which need discussion, planning, and support.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about Prostate Biopsy

1. What is a Prostate Biopsy?

A prostate biopsy is a medical procedure in which small samples of tissue are removed from the prostate gland to evaluate the presence of cancerous or abnormal cells. It is the definitive method for diagnosing prostate cancer. Most men undergo a biopsy after abnormal findings, such as elevated PSA levels or suspicious areas on MRI scans. During the biopsy, the physician uses ultrasound or MRI guidance to target specific regions of the prostate. The extracted tissues are examined by a pathologist, who identifies whether cancer is present and assesses its aggressiveness through the Gleason grading system. A biopsy remains the most accurate method of detecting prostate cancer early, which is crucial for effective treatment and long-term survival.

2. Why is a Prostate Biopsy Necessary?

A biopsy is recommended when screening tests indicate potential abnormalities. High or rising PSA levels, abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE), and suspicious lesions on MRI imaging are the most common reasons for referral. A biopsy helps differentiate between benign conditions such as prostatitis or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and actual malignancy. It also helps determine the type of cancer, how fast it is likely to grow, and whether immediate treatment is necessary. Without biopsy confirmation, doctors cannot reliably diagnose or plan treatment for prostate cancer.

3. How Is the Prostate Biopsy Performed?

There are two main approaches: transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy (TRUS) and transperineal biopsy.

-

Transrectal biopsy: An ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum, and a spring-loaded needle collects tissue samples through the rectal wall.

-

Transperineal biopsy: Needles are inserted through the skin between the anus and scrotum. This method lowers infection risk and allows more precise sampling.

Typically, 10-14 core samples are taken. In MRI-fusion biopsies, real-time ultrasound images are merged with MRI scans to target suspicious areas more accurately. The procedure usually takes 15-30 minutes and can be done under local anesthesia or sedation.

4. Does the Procedure Hurt?

Most men experience mild discomfort rather than significant pain. Local anesthesia numbs the prostate area, making the process tolerable. Some pressure during needle sampling is normal. After the procedure, patients may have mild soreness, fullness in the rectum, or discomfort while sitting, which usually subsides within 24-48 hours. Pain relievers, warm baths, and adequate rest help improve comfort during recovery.

5. What Are the Risks and Side Effects of a Prostate Biopsy?

Common side effects include temporary blood in the urine, semen, or stool-often lasting several days to weeks. Minor rectal bleeding or discomfort is normal. More serious complications are rare but can include infection, fever, urinary retention, or excessive bleeding. Antibiotics are prescribed to reduce infection risk. Transperineal biopsies have even lower infection rates. Patients should contact a doctor immediately if they experience high fever, difficulty urinating, or persistent pain.

6. How Should I Prepare for a Prostate Biopsy?

Preparation typically involves stopping blood-thinning medications, taking prescribed antibiotics, and performing a cleansing enema before the procedure. Patients should inform their doctor about existing medical conditions, medications, allergies, or past infections. Eating a light meal before the procedure is recommended unless sedation will be used. Clear instructions will be provided based on the biopsy method chosen.

7. What Happens After the Biopsy?

Most patients return home the same day and resume light activities quickly. It is normal to see blood in urine or semen for several days. Sexual activity, heavy lifting, and strenuous exercise should be avoided for 48-72 hours. Drinking plenty of fluids helps clear minor bleeding faster. If discomfort persists, pain relievers and warm sitz baths provide relief. Patients should monitor for signs of infection, such as fever or chills.

8. How Long Do Biopsy Results Take?

Results typically take 5-10 days. The pathology report will specify whether cancer cells are present and describe their characteristics. The most important part of the report is the Gleason score, which helps measure how aggressive the cancer is. Results may also identify inflammation, precancerous changes, or benign conditions. The doctor will explain the findings and recommend next steps.

9. What If My Biopsy Shows Cancer?

If cancer is detected, treatment options depend on factors such as Gleason score, PSA levels, cancer stage, and patient health. Choices may include active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, focal therapy, or combination treatment. Not all prostate cancers require immediate intervention. Many low-grade tumors grow slowly and may be monitored safely with active surveillance. Your doctor will guide you on the best option based on your diagnosis.

10. Can a Prostate Biopsy Miss Cancer?

Yes, biopsies can occasionally miss cancer, especially if the tumor is small or located in difficult-to-reach regions. If PSA levels continue rising or MRI scans remain suspicious, doctors may recommend a repeat biopsy or an MRI-fusion biopsy for improved accuracy. Regular monitoring ensures early detection if abnormalities progress.