Introduction to VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect) Closures

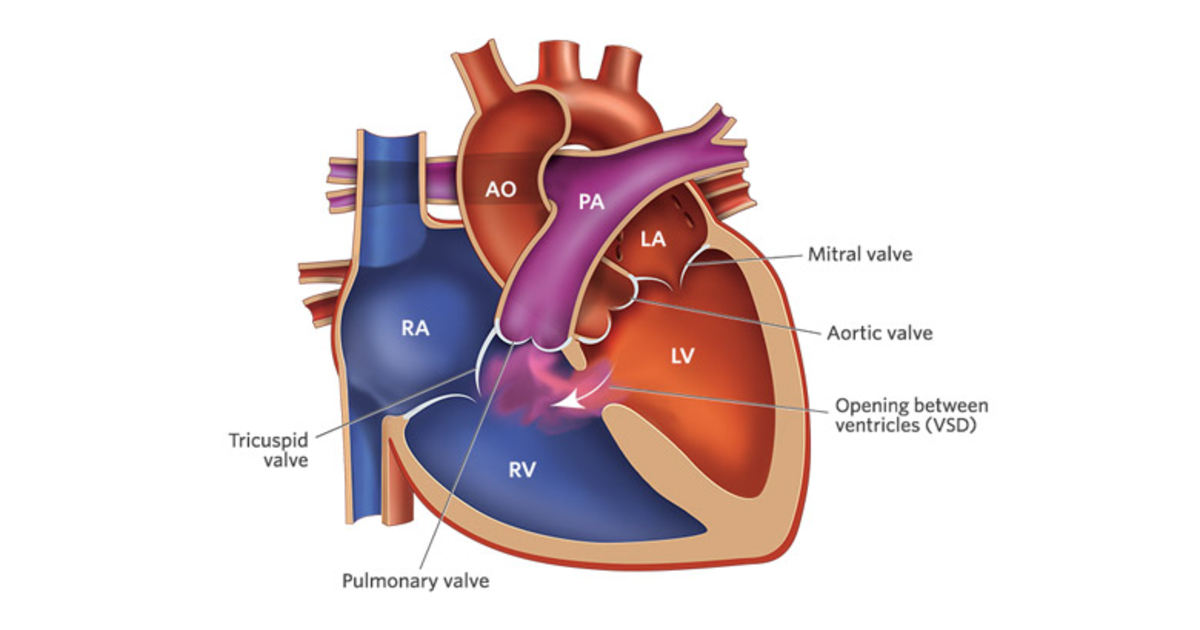

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) is a congenital heart condition where there is a hole or abnormal opening in the septum that separates the heart's two lower chambers, the ventricles. This defect allows blood to flow between the two ventricles, which in a normal heart would not happen. The left ventricle, which pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body, leaks blood into the right ventricle, which pumps oxygen-poor blood to the lungs. This can lead to inefficient circulation, putting extra strain on both the heart and the lungs.

What happens in a VSD?

In a healthy heart, the septum ensures that the oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart is sent to the body, while the oxygen-poor blood from the right side is sent to the lungs. When there is a VSD, this separation is compromised, and oxygen-rich blood mixes with oxygen-poor blood, reducing the efficiency of the circulatory system. The severity of the condition depends on the size and location of the hole in the septum.

Types of VSDs:

-

Membranous VSD: The most common type, located in the upper portion of the septum.

-

Muscular VSD: Found in the muscular portion of the septum, sometimes leading to multiple holes.

-

Inlet VSD: Located near the tricuspid valve, which is the valve between the right atrium and right ventricle.

-

Outlet VSD: Located near the pulmonary valve that connects the right ventricle to the lungs.

-

Supracristal VSD: Located near the aortic valve and typically associated with more complex heart issues.

VSDs can vary significantly in terms of their size, shape, and the effect they have on the heart. While some may be small and asymptomatic, others can lead to serious complications, including heart failure, if not addressed properly.

Treatment:

Treatment for VSDs typically involves a procedure to close the hole in the septum. This can be done surgically or through a less invasive method using a catheter. The decision on how to treat the condition depends on the size of the defect, the severity of symptoms, and the age of the patient.

Causes and Risk Factors of VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect) Closures

Ventricular Septal Defect is primarily a congenital heart defect, which means it develops during fetal development. The exact cause of the defect in many cases is not clear, but several factors can increase the risk of a VSD developing.

Developmental Origin:

VSDs occur during fetal development, usually early in pregnancy, when the heart is forming. During this time, the septum that divides the ventricles does not develop properly, leaving a hole. The septum may be completely or partially absent, leading to a VSD. While the exact cause of this failure to form correctly is not always known, various factors can contribute.

Genetic Factors:

Certain genetic conditions increase the likelihood of a VSD. Conditions like Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and DiGeorge syndrome are often associated with congenital heart defects, including VSDs. Additionally, a family history of congenital heart defects may increase the risk for a child to be born with a VSD.

Environmental Factors:

Certain environmental influences during pregnancy may contribute to the development of congenital heart defects. These include:

-

Maternal infections: Some infections that occur during pregnancy, such as rubella (German measles) or cytomegalovirus, can lead to congenital defects like VSD.

-

Substance use: Smoking, alcohol consumption, or drug use during pregnancy can negatively affect fetal development, including the formation of the heart.

-

Maternal health conditions: Uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, or high blood pressure in the mother can increase the risk of congenital heart defects in the baby.

Other Contributing Factors:

-

Premature birth: Babies born prematurely are at an increased risk of developing heart defects, including VSDs.

-

Age of the mother: Advanced maternal age (over 35 years) has been linked to an increased risk of congenital heart defects.

Is VSD Preventable?

Because the causes of VSD are not entirely understood, there is no foolproof way to prevent it. However, maintaining good prenatal care, avoiding harmful substances, and managing chronic conditions can help reduce the risk of VSD in newborns.

Symptoms and Signs of VSD

The symptoms of a VSD depend on the size of the hole in the septum and whether the defect is causing any complications. Some VSDs are small and cause no symptoms at all, while others can cause significant problems with heart function. Below are the common signs and symptoms associated with VSD.

Symptoms in Infants:

-

Heart murmur: This is often the first sign of VSD. A murmur is an abnormal heart sound caused by blood flowing through the hole in the septum. It is usually detected during a routine physical exam.

-

Difficulty feeding: Infants with larger VSDs may have difficulty feeding due to shortness of breath or fatigue.

-

Failure to thrive: Babies with VSD may not gain weight or grow at the expected rate because the defect puts extra strain on their heart and lungs.

-

Breathing problems: Rapid breathing, shortness of breath, or labored breathing, especially during feeding or exertion, are common signs of larger VSDs.

-

Frequent lung infections: VSDs can increase the amount of blood flowing to the lungs, which can lead to repeated respiratory infections.

Symptoms in Older Children and Adults:

-

Shortness of breath: As the individual grows, they may experience difficulty breathing or feel winded during physical activity.

-

Fatigue: Older children and adults with VSD may feel excessively tired, especially after exercise, because their heart is working harder than usual.

-

Exercise intolerance: People with untreated VSD may find it difficult to engage in physical activities without getting tired or out of breath.

-

Palpitations: In some cases, individuals with VSD may experience irregular heartbeats or palpitations as their heart compensates for the defect.

When Symptoms Are Mild:

Small VSDs may be asymptomatic, meaning they don't cause noticeable symptoms. These defects may close on their own over time, and the person may live without ever knowing they have the condition.

Diagnosis of VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect)

Diagnosing a VSD typically begins with a physical exam. If a heart murmur is detected during auscultation (listening with a stethoscope), further diagnostic tests will be performed to confirm the presence of a VSD and determine its size and location.

Key Diagnostic Tests:

-

Echocardiography (Echocardiogram):

-

An echocardiogram is the most important tool for diagnosing VSD. It uses sound waves to create an image of the heart, allowing doctors to visualize the septal defect, assess its size, and evaluate the heart's function.

-

A Doppler echocardiogram may also be used to assess blood flow and determine how much blood is shunting between the ventricles.

-

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG):

-

An ECG records the electrical activity of the heart and helps identify irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias) or heart enlargement that may result from the VSD.

-

-

Chest X-ray:

-

A chest X-ray can help assess the size of the heart and detect any changes in lung structure, such as fluid buildup or enlargement of the heart due to VSD.

-

-

Cardiac Catheterization:

-

This test may be used in complex cases where precise measurements of heart pressure are needed, especially to evaluate the severity of the defect and determine if surgery is required.

-

Treatment Options for VSD Closures

The treatment for VSD depends on the size of the defect, the age of the patient, and the severity of symptoms. There are two primary approaches to treating VSD: medical management and surgical intervention.

Medical Management:

-

Observation: For small VSDs that are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, doctors may recommend a wait-and-see approach. Regular follow-up visits with echocardiograms can monitor the defect's progress.

-

Medication: Medications such as diuretics (to reduce fluid buildup) or ACE inhibitors (to relax blood vessels and reduce strain on the heart) may be used to manage symptoms and help the heart function better.

Surgical Options:

-

Open-heart Surgery: If the VSD is large or causing significant symptoms, open-heart surgery may be required. The surgeon will either sew the hole shut or place a patch over the hole to prevent blood from flowing between the ventricles. This surgery is typically performed when the child is around six months to one year old.

-

Catheter-Based Closure: For certain types of VSDs, a less invasive approach may be used. A device is inserted through a catheter (usually through a blood vessel in the groin) and deployed across the hole in the septum to seal it. This method is often used for VSDs in specific locations that are accessible through a catheter.

Prevention and Management of VSD

While VSD is not always preventable, there are steps that can reduce the risk of congenital heart defects, including:

-

Prenatal Care: Regular prenatal visits to monitor the health of the mother and fetus are crucial. Avoiding smoking, alcohol, and drugs during pregnancy can significantly lower the risk of VSD.

-

Folic Acid: Taking prenatal vitamins, especially folic acid, can help prevent certain types of birth defects, though its direct impact on VSD is unclear.

-

Early Diagnosis and Monitoring: Regular follow-ups and early diagnosis are essential for children born with VSD to ensure the defect doesn't cause long-term complications.

Complications of VSD (Before and After Closure)

Before Closure:

If left untreated, VSD can lead to several complications:

-

Heart Failure: The heart may become weakened from the increased workload of pumping extra blood, leading to heart failure.

-

Pulmonary Hypertension: The extra blood flow to the lungs can increase pressure in the pulmonary arteries, potentially causing lung damage over time.

-

Arrhythmias: Irregular heartbeats can develop as the heart tries to compensate for the defect.

After Closure:

Even after closure, there can be some risks:

-

Residual Shunts: Sometimes, the hole may not close completely, leading to a small residual shunt.

-

Infections: In rare cases, infections such as endocarditis can occur after surgery or catheter closure.

Living with VSD (Before and After Closure)

For many children and adults, VSD is a manageable condition. After successful closure, most individuals lead normal, active lives. It's essential to have regular check-ups with a cardiologist to monitor heart function and ensure there are no long-term complications.

Living with VSD, both before and after closure, involves monitoring symptoms and following medical advice closely. Post-surgery, patients can typically return to normal activities, including exercise and sports, once cleared by their healthcare provider.

Top 10 Frequently Asked Questions about >Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) Closure

1. What is a Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) and why does it require closure?

A Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) is a hole in the septum, the wall that divides the left and right ventricles of the heart. This defect allows oxygenated blood from the left ventricle to mix with deoxygenated blood in the right ventricle. Normally, the left ventricle pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body, while the right ventricle pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs. When a VSD is present, this mixing of blood can lead to inefficient circulation, putting extra strain on the heart and lungs, and potentially causing long-term complications.

A VSD may need to be closed if the defect is large enough to cause significant symptoms or complications, such as:

-

Heart failure due to overworked heart chambers

-

Pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs)

-

Poor growth in infants

-

Frequent respiratory infections or other lung issues

Closure of the VSD prevents these complications and helps restore normal blood flow through the heart, reducing the strain on the cardiovascular system.

2. When is VSD closure necessary? Can all VSDs be closed surgically?

Not all VSDs require surgical closure. Small VSDs that do not cause significant symptoms may be monitored with regular checkups and may even close on their own as the child grows. However, surgery is typically recommended when:

-

The VSD is large and causing symptoms such as breathing difficulty, fatigue, poor growth, or frequent respiratory infections.

-

The defect causes significant shunting of blood (excessive blood flow from left to right), which can strain the heart and lungs.

-

There are signs of pulmonary hypertension (increased pressure in the lungs) or heart failure as a result of the VSD.

-

If the VSD is located in a critical area and is associated with other congenital heart defects or complications.

Surgical closure is usually considered when these factors are present, and when non-invasive treatments (like medication) are not sufficient to manage the condition.

3. How is VSD closure performed? What are the treatment options?

VSD closure can be performed in one of two main ways:

-

Open-Heart Surgery: In this traditional approach, a surgeon makes an incision in the chest, typically through the breastbone (sternotomy), to access the heart. The heart is temporarily stopped, and the surgeon uses a patch or sutures to close the VSD. This approach is generally used for larger VSDs or when the defect is in a location that is difficult to access using less invasive methods.

-

Minimally Invasive (Catheter-Based) Closure: For certain types of VSDs (particularly muscular VSDs or small, less complex defects), a catheter-based procedure may be used. A catheter is inserted into a blood vessel (usually through the groin) and threaded up to the heart, where it delivers a special occluder device that closes the hole without the need for open-heart surgery. This method is less invasive and typically involves a shorter recovery time.

The choice of method depends on the size, location, and complexity of the VSD, as well as the patient's overall health and age.

4. What benefits can patients expect after VSD closure?

After VSD closure, most patients experience significant improvements in their health, including:

-

Improved heart and lung function: By closing the VSD, normal blood flow is restored, reducing strain on the heart and lungs. This typically leads to a reduction in symptoms like breathlessness, fatigue, and heart palpitations.

-

Better growth and development (especially in children): Many infants and children with VSDs experience poor growth due to inadequate oxygenation. Once the defect is closed, improved oxygen circulation supports better growth, weight gain, and overall development.

-

Reduced risk of complications: By preventing excessive blood flow to the lungs and reducing the strain on the heart, surgery reduces the risk of developing pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, and long-term cardiovascular problems.

-

Improved quality of life: For individuals with symptoms such as difficulty exercising, fatigue, or shortness of breath, closing the VSD can improve overall physical functioning and quality of life.

5. What are the risks and complications of VSD closure?

Like any surgical procedure, VSD closure carries some risks, including:

-

Infection: There's always a risk of infection after surgery, especially in the chest cavity or the area around the heart.

-

Bleeding: The surgical site or the heart may experience bleeding during or after the procedure.

-

Arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm): During or after surgery, there may be disturbances in the heart's electrical system, leading to arrhythmias.

-

Damage to heart valves: In some cases, the surgery may inadvertently affect the heart valves, leading to issues like regurgitation (leakage).

-

Residual VSD: Occasionally, the closure may not be fully effective, leading to persistent shunting or the need for additional surgery.

-

Device-related issues (for catheter-based closures): If a catheter-based occluder is used, there's a small risk of device dislodgement or incomplete closure.

Most complications are rare, and with proper care, the risks can be minimized.

6. What is the recovery process after VSD closure?

Recovery after VSD closure depends on the type of surgery performed:

-

After open-heart surgery: Patients typically stay in the hospital for 3–7 days for monitoring and to manage pain. Recovery includes avoiding physical exertion, following a strict medication regimen, and gradually resuming daily activities.

-

After catheter-based closure: This minimally invasive procedure typically has a shorter recovery time. Patients may need to stay in the hospital for a day or two for monitoring, but they can generally return to light activities within a week.

-

Follow-up care: Regular follow-up appointments are necessary to ensure the defect has been fully closed and that there are no complications. This may include echocardiograms or other imaging tests to monitor heart function and healing.

It may take several weeks to months for the heart to fully heal, and full physical recovery can take up to 6 months.

7. Can VSD closure be done in adulthood?

Yes, VSD closure can be performed at any age, though it is more commonly done in childhood, especially when the condition is detected early. In adults, VSD closure is often performed if the defect was not diagnosed in childhood or if symptoms have developed later in life. Adults who experience symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, or chest pain related to a VSD may benefit from surgical closure, even if the defect is diagnosed later in life. Early detection and timely closure in adults can prevent further damage to the heart and lungs.

8. What should I expect in terms of long-term outcomes after VSD closure?

The long-term outcomes after VSD closure are generally excellent, with most patients going on to lead healthy, active lives. For children, closure of a VSD typically results in:

-

Normal growth and development: Once the defect is closed, children typically experience improvement in physical development and overall health.

-

Reduced risk of future heart problems: Proper closure helps prevent the development of complications like pulmonary hypertension or heart failure.

For adults, successful closure can prevent the progression of heart damage, improve exercise tolerance, and eliminate symptoms related to the VSD. However, lifelong monitoring may be necessary to check for any residual defects or heart issues.

9. What are the long-term care and follow-up requirements after VSD closure?

Long-term follow-up is important to ensure the success of the VSD closure and to monitor for any potential complications. Depending on the patient's age and health, this may include:

-

Routine cardiac checkups: To monitor heart function, ensure there are no residual defects, and check for issues such as arrhythmias or valve problems.

-

Regular echocardiograms: To assess the heart's structure and function after the surgery.

-

Lifestyle adjustments: Adopting a heart-healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet, regular physical activity, and avoiding excessive stress, can help maintain cardiovascular health.

Follow-up visits are typically required at 6 months, 1 year, and then on a long-term basis as recommended by the healthcare provider.

10. What alternatives exist for VSD closure if surgery is not an option?

For some individuals, especially those with small VSDs, a more conservative approach may be appropriate:

-

Watchful waiting: For very small VSDs that cause no symptoms or health issues, doctors may recommend regular monitoring rather than immediate surgery.

-

Medication: In some cases, medications like diuretics or ACE inhibitors may be used to manage symptoms, such as fluid buildup or high blood pressure, especially in infants or young children.

-

Percutaneous closure: In certain cases, a catheter-based procedure may be considered as an alternative to open surgery, especially for small, less complicated VSDs.

While these alternatives may help manage the condition, surgery remains the most effective and permanent solution for larger or symptomatic VSDs.